I first saw Earth, Wind & Fire live in 1987 at Radio City Music Hall. I came down from the Bronx with Rene, a friend I went to school with. For us—kids from a not-so-nice place, in a not-so-nice time—EW&F managed to project cool while remaining squeaky clean. Their 1972 album, Last Days and Time, even had a song called “Mom.”

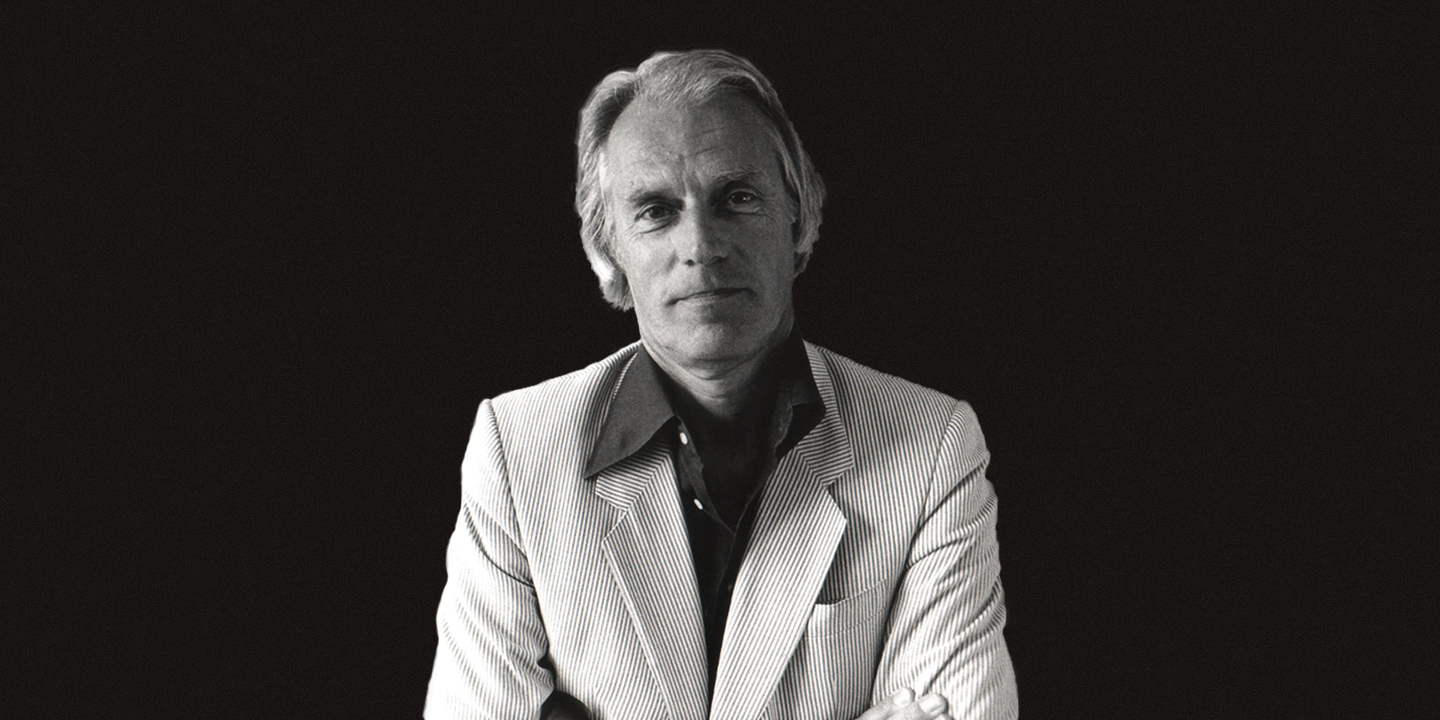

But by the late ’80s, the band wasn’t what it had been. The tour wasn’t a comeback, per se, but something was different. A lot was different, in fact. Many of the original members were gone, and the clothes changed: out were the capes and platform shoes; in were loose-fitting blazers with rolled-up sleeves. The vibe wasn’t the same, but the message was—and Maurice White was that message. White, who passed away yesterday at 74, was Earth, Wind & Fire. He was the reason we were all at Radio City in the first place.

After working as a session drummer for Chess Records, White started the band in Chicago as the Salty Peppers in 1969 before moving them to Los Angeles and going onto effortlessly—and joyously—fuse a variety of African-American musical forms: jazz, blues, gospel, soul, funk, R&B, disco. Their music was a celebration, and everyone was invited. White was inclusive, but the band was often derided by white rock fans and smarty-pants critics as “crossover.” Not that it mattered; people listened, sang along, danced.

As a vocalist, White was good, but not in the category of the great soul and R&B singers of the ’60s and ’70s golden era; he wasn’t Levi Stubbs, David Ruffin, Teddy Pendergrass, Bobby Womack, Donny Hathaway, Marvin Gaye. (The famous, soaring falsetto long-associated with EW&F belongs to Philip Bailey.) But beyond being the architect of the band, White excelled as a lyricist, composer, and arranger. The group’s ballads, often at least co-written by White, were emotionally rich and memorable, as were their covers of songs like Pete Seeger’s “Where Have All the Flowers Gone” and the Beatles’ “Got to Get You Into My Life.”

In the early ’70s, White’s band veered toward a flower-child aesthetic, somewhere between Sly and the Family Stone and the Fifth Dimension (see: the cover of 1973’s Head to The Sky). Those records didn’t churn out the super hits EW&F became best-known for, but they are grittier, more soulful. Then came the breakout in 1975: That’s The Way of the World. It was a soundtrack for a movie no one saw starring Harvey Keitel as a record producer, and the band members themselves, who barely had any dialogue, as “The Group.” But it gave us the title track, along with “Shining Star” and Philip Bailey’s opus “Reasons,” which Charles Burnett used to memorable effect in his great film Killer of Sheep three years later. (EW&F also performed the music for Melvin Van Peebles groundbreaking 1971 movie Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song.)

White recognized the importance of the sound of brass—a mainstay in black American music—and the EW&F horn section was legendary. This was a big band, though not in the Ellington sense. White used two guitars, bass, keyboards, drums, multiple percussionists, and those horns. He used strings on a couple of albums, too.

EW&F explored their African roots: White played the kalimba, an African thumb piano, and started a production company named after the instrument; the thunderous opening number of the 1975 live album Gratitude was called “Africano”; they did a 13-minute instrumental entitled “Zanzibar” in 1973; Egyptology was an ongoing interest. White also looked to Brazil, doing on a short version of Milton Nascimento’s “Ponta De Areia” (a wink to Wayne Shorter, who did his own version of the song).

Fitting their global curiosity and welcoming sweep, the band’s world tours were epic by the late ’70s. Magician Doug Henning was an advisor; Verdine White, the bassist and Maurice’s brother, would levitate. Black bands had toured the world before, but rarely in stadiums, and none with a stage show as conceived by Maurice White.

The cover of the 1980 double album Faces—featuring visages from all over the world, of all different backgrounds—was White’s homage to inclusiveness. On the eve of Reaganomics, his message was one of hope, brotherhood, and humanity. It always was.

By 1987, fascinations with Egypt and the intergalactic were no longer, replaced with songs with titles like “Money Tight” and “System of Survival.” The band fell out of favor, though younger musicians—Common, OutKast, D’Angelo, so many others—would eventually pay tribute. They knew what trends and prissy critics didn’t: That EW&F created something timeless.

So that 1987 concert was my first chance to see what Maurice White built. It wasn’t the most memorable show, but I’ll never forget it.

Michael J. Agovino is the author of The Bookmaker and The Soccer Diaries.