![Paper Trail: Unconventional Idol: Kim Gordon's <i>Girl in a Band</i>]()

"KILL YOUR IDOLS," Sonic Youth violently declared, and over 30 years, the band regularly traversed the chameleonic space between idolatry and irony. "I was totally into hero-worshipping male guitarists," Kim Gordon once said, with indecipherable dryness, talking about her youth in the 1987 film Put More Blood Into the Music, a funny, avant-garde portrait of the group. Five years later, when she appeared on MTV promoting Hole's Pretty On the Inside, which she produced, the VJ asked, "Is producing something you've done a lot of?" to which Gordon deadpanned, "Yes, I try and do it at least once a week." Her approach to talking about herself always seemed to be sarcastic, distanced, Warholian.

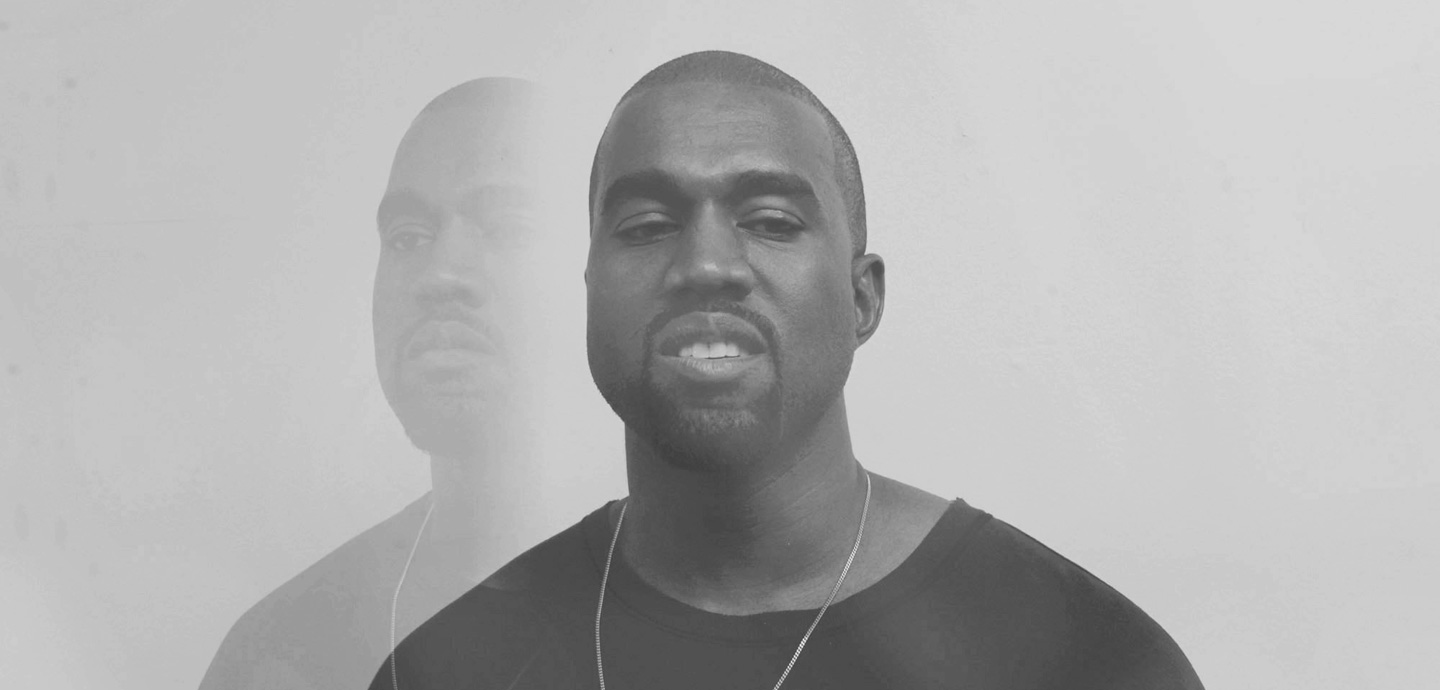

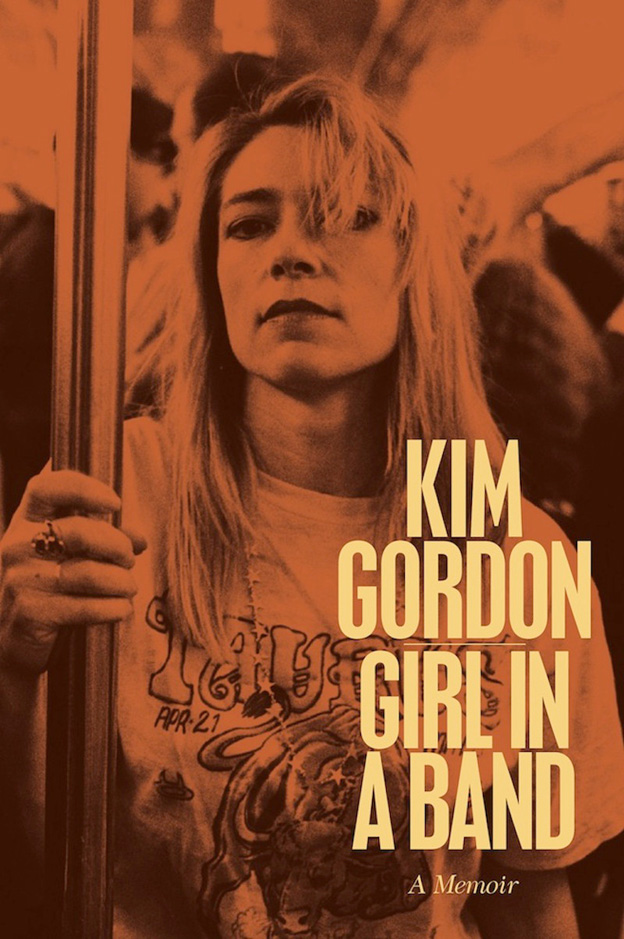

In Girl in a Band, Gordon's new memoir, she takes the Ray-Bans off the story of her life, so to speak. Like last year's essay collection Is It My Body?, Gordon's prose is as tonally conversational and idea-driven as her speak-singing style (which itself was informed, she writes, by spacious jazz phrasing and ‘60s girl group the Shangri-Las). Girl in a Band chronicles Gordon's "faux-hippie" adolescence in California, Hawaii, and Hong Kong—as she smoked pot, listened to Joni Mitchell, and channeled Françoise Hardy—and her subsequent penniless move to New York City in the early-‘80s era of No Wave noise and Basquiat. (She could only afford her first apartment due to a huge insurance check following a car accident.) While in the city, she wrote magazine articles about "male bonding" in the context of the downtown scene, unlocking her life as a musician. As in Gordon's art itself, the book's appeal is often in its subtleties: Her favorite color is turquoise; she thinks Emily Dickinson is corny; her dog is named Merzbow.

Listen to a playlist of Sonic Youth songs with Gordon on lead vocals:

Girl in a Band also discusses the end of Gordon’s marriage to Thurston Moore in excruciating detail; she writes of feeling more alone than ever at Sonic Youth's last show, of taking Xanax to make it through the band's final practices, of not having it in her to actually say goodbye. But the most interesting relationships Gordon describes are those with her daughter, Coco, and her artist friends Dan Graham and the late Mike Kelley (who, in one great passage, fervently argue over the origins of punk). Gordon gives many pages to her troubled relationship with her "brilliant, manipulative, sadistic" brother, Keller, a paranoid schizophrenic who was the cause of her lifelong "incommunicative" ways: "The image a lot of people have of me as detached, impassive, or remote is a persona that comes from years of being teased for every feeling I ever expressed," she writes. That, combined with the non-linear ideas culled from French New Wave cinema, Buddhist philosopher Alan Watts, and acid lead her towards abstraction, never feeling comfortable with "bold, definitive statements." Gordon's final words in Girl in Band are "I guess I am"—a conclusion that is telling in its ambiguity.

But even after reading these 288 pages, it's still hard to imagine Gordon actually talking about herself for more than 20 minutes. At her Girl in a Band launch event on Monday at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, she instead commentated a series of videos as context for the book—scenes from 1966's Blow Up, the 1970 Rolling Stones film Gimme Shelter, and the Dylan documentary No Direction Home, as well as live footage of Joni Mitchell, CSNY, Sex Pistols, the Stooges, Nirvana, and Bikini Kill. The clips showed examples of live music experiences gone awry—made great due to their total chaos, rupturing of expectation, and unconventional transfer of power—as the "sacred barrier" between the crowd and the spectacle was broken. "It's not a seamless idea of entertainment," Gordon said of these spontaneous moments, "I like when something falls apart." Gordon's book, and life, too, has taken unlikely turns that make her an even more dynamic and relatable emblem of poised cool in the history of American rock'n'roll.

![]()

Pitchfork: Early in Girl in a Band, you write that performing had a lot to do with being fearless. What was your most recent act of fearlessness?

Kim Gordon: Writing the book, pretty much. It's something I never thought I would do. I guess I naturally would have been more cautious, but sometimes, when life gets in front of you, you just go with it. But I also held back—there's a lot of read-between-the-lines stuff, which is how I am anyway. There's lots of subtext. I'm basically trying not to think about the fact that so many people now know a lot about me.

Pitchfork: Did you keep diaries over the years or were you writing from memory? I read a 2012 issue of the German publication Mono Kultur where you said you'd spent more time thinking about the future than the past.

KG: I wrote primarily from memory. As far as projects I've done, I don't think about them so much—I'm just not into archiving things. I'm always looking forward to the next thing. There were things I'd written about at length before—I had a book of art writing that came out last spring, which also included a Village Voice diary about touring—but I'm more of a believer that important things come back. You can't write about everything, so you put in what tells a cool story. I'm more of a minimalist.

Pitchfork: Did you interview any family members?

KG: Not really. I hardly have any family.

People who sometimes come across as really confident or

strong are actually just not letting themselves be vulnerable,

in a way—they're never really going to make great work.

Pitchfork: Is there anything you learned about yourself from the process of writing this book?

KG: There was one thing—like, maybe I ended up playing music with a bunch of guys because I was searching for some better brotherly relationship, since I had such a shitty one with my own brother.

Pitchfork: One thing you explore in the book is the foundation of your own shyness. It was interesting to learn about how your brother's behavior impacted that. Did your shyness—and being a generally quieter, more cautious rockstar—make it difficult to write the more opinionated parts of the book?

KG: Writing is different from talking. I feel like a different person when I'm writing. I look back at things I wrote a long time ago and I'm like, "Did I write that?" It's a different process. It's like having a medium in front of you that somehow allows you to have some distance. I was aware of how [my brother] affected me growing up, but it was only recently that I realized how, when you're onstage, or doing something creative, that it's this free space.

Pitchfork: While reading these parts about your shyness, I thought about something you once said about how passiveness can be its own form of rebellion. Was there a specific point in your life that you realized you could harness that and turn it into a form of power?

KG: At some point I became more accepting about who I was. People who sometimes come across as really confident or strong are actually just not letting themselves be vulnerable, in a way—they're never really going to make great work. You have to allow yourself into the work somehow, and be honest about who you are. But that's hard to do. If you don't take risks, you don't get as much back.

Pitchfork: At this point in your life, do you feel like you're less shy than when you first started making music?

KG: [laughs] It depends on who I'm talking to. I can be incredibly shy. It's just a mood.

Watch footage from a 1985 Sonic Youth performance in the Mojave Desert that Gordon picks out as one of her favorite shows ever in Girl in a Band:

Pitchfork: Another line from the book that stuck out for me was when you were talking about your divorce. You call it "the most conventional story ever." Throughout the book, the idea of convention is revisited often, like it's the most awful thing.

KG: Well, convention isn't awful, it's just not something that I really aspire to. I certainly admire other people who do more conventional work, whether it be music or writing. It's just not who I am. I have actually walked around with this feeling for most of my life, that I'm this very conventional person from a middle-class upbringing, and that other people are more eccentric or weird. I walk around thinking to myself, "Yes, I'm that, but I'm also totally not that." It's funny—it's just a blind spot about myself. But I realize that there's not a lot conventional about my life or anything that I make, except that I have a child and was in a marriage and had a family. Because of our lifestyle of being in a band, I maybe overcompensated and wanted [Coco] to have this really solid foundation.

Pitchfork: What is the most unconventional thing about your life now?

KG: Just the kind of work that I make. My art career has not been conventional. I don't do one kind of painting, or have a focus. The music I make is experimental. I travel a lot. I'm drawn to people who are unconventional. I feel a bit like a teenager right now. My daughter's in college, and I feel very free and independent. At my age, I never thought I would be, like, dating. I'm not sure exactly where I'm moving to. There are a lot of question marks.

Pitchfork: It sounds pretty exciting to me.

KG: It is! Actually. It is. I mean, I'm really grateful for the opportunities that have happened in the last couple of years. I had this survey show at White Columns [in 2013] that was really great, and I have a show at 303 Gallery in June. And putting out an experimental double record with Body/Head and having it be well-received was just shocking. It was really gratifying. There have been a lot of positives.

If you don't fit into a certain type, there's

a lot of strength in just being who you are.

Pitchfork: You said that you feel like a teenager, which reminded me of something you posted on Twitter a while ago: "Better to be a young older person than an old young person." As someone in my 20s, that really stuck with me. How do you channel that energy? What does age mean to you now, if anything?

KG: I feel like a lot of people can relate to not exactly feeling whatever age they are; everyone carries around some age inside of them that's way younger than what they actually are. It's shocking to realize, "Oh, I'm actually kinda old." It's a slippery thing. There's so much pressure to be young. There are certain areas of culture, on TV and in the media and movies, where you get the impression that everyone is only 20. You can also be young and wish you were old. There are certain subcultures that are interesting, like surfing, where people from different generations seem more intertwined, but I don't see that as much in the music world.

I have a lot of responsibilities now, but I feel a certain lightness from opening up. I'm a really slow developer. I realized that there is an aspect of myself that's kind of arrested from how my brother affected me, which makes feeling like a teenager seem more positive, but it's also probably horrible in ways. I just feel unstrung, a little bit disoriented in my life. I do have a very strong sense of who I am, but where I'm located in the world is a little bit unsure.

Pitchfork: What would you want younger people to learn from the book?

KG: It's important to find a thread in your life and have the confidence to follow it, if it's leading you somewhere interesting. And if you don't fit into a certain type, there's a lot of strength in just being who you are.

My Favorite Cereal

My Favorite Cereal

Favorite Cartoon Character

Favorite Cartoon Character