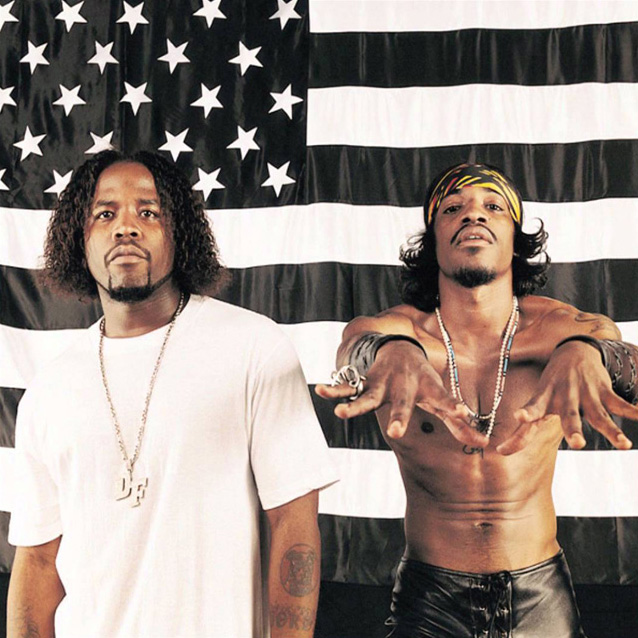

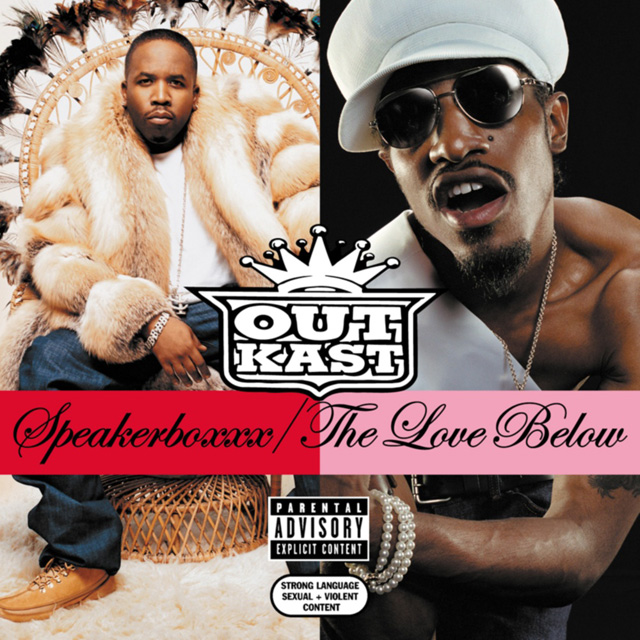

Ten years after from their last major record, Speakerboxxx/The Love Below, we trace Big Boi and Andre 3000's path from Southern vanguards to the most universally beloved rappers in the world with a career-spanning essay followed by separate pieces on each of their six albums.

Weird Storms in the Wrong Season

By Jeff Weiss

Before there was love below, there were boos. The two dope boys in a Cadillac had made a left turn and wound up in the middle of a civil war at Madison Square Garden's Paramount Theater on a soggy August night in 1995. Brawls erupted in the audience. Tensions were hair-trigger. When OutKast shocked the Source Awards audience by winning Best New Rap Group, it was like being fed to the firing squad.

The first shots took the form of words. Earlier that evening, Suge Knight—6-foot-3, 330 pounds, Blood-red button-up shirt—glowered at the audience like a hellbound offensive lineman: “If any artists out there want to be artists and stay a star… and don’t want to worry about the executive producer… all in the videos… all on the records... dancing.” Knight let that last word linger, a personal grenade hurled at Puff Daddy. “Come to Death Row!”

Snoop Dogg escalated the confrontation to the entire seaboard: “The East Coast don’t got no love for Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg and Death Row?” he sneered, marine-blue bandanna tied around his neck, brandishing a club at the hostile New York crowd—a murder trial already awaiting him back home. “Well… let it be known!”

OutKast was collateral damage. It didn’t matter that Puffy directed the video for their debut single, “Players Ball”, or that they’d previously opened up for Biggie. The New York crowd only acknowledged Bad Boys and boom-bap. Mobb Deep. Boot Camp Clik. Nas. Wu-Tang or protect your neck. They looked at the southern players like country cousins eating chitlins and smoking stress. What good is a '77 Seville when you’re riding the subway?

This mentality missed Atlanta's Andre Benjamin and Antwan Patton. Their red clay funk emerged from the Dungeon—the nickname for the basement studio owned by Rico Wade, one third of their production squad, Organized Noize. They’d come up on Brand Nubian, Poor Righteous Teachers, A Tribe Called Quest, and Rakim, just like everyone else in the room. They’d break danced and bought Ron G mixtapes at the 5 Points Flea Market. Their realness was beyond reproach.

The heckling that night transcended personal disrespect; it implicitly attacked the drawl, slang, and soul food of the culture that spawned them. As Andre threatened on the duo's platinum-selling 1994 debut album Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik: “Talk bad about the A-Town and I’ll bust you in your fucking mouth.” Barely 20 years old, Dre had yet to adopt the “3000.” He’d recently gone sober, vegetarian, and grown dreads, swapping his Braves jersey for a polyester turban. Standing before a crowd in Karl Kani, Phat Farm, and Versace, OutKast looked and felt alien. The meaning of the group’s name had come to life in front of the howling mob. Andre silenced them with six words: “The South got something to say.”

OutKast understood that the most profound answers are often implied. Rappers unable to exit their own orbit might have directly addressed the incident at the Source Awards. OutKast located it within a deeper pattern of dislocation. They were able to internalize the last century of black musical visionaries including Son House, Chuck Berry, Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, Curtis Mayfield, Sly Stone, George Clinton, Prince. But they also completely lack precedent. They take you from Atlanta to Atlantis and back in the same stanza.

Their identity as outsiders gave them perspective, their empathy allowed them to connect, and their wisdom offered the ability to see through bullshit. They could write a song about “floating face down in the mainstream” on a certified platinum album. We routinely celebrate the contradictions of artists as a badge of complexity, but OutKast was the rarity able to reconcile commerce, human decency, and purity of vision. There are no cynical radio grabs. No guest appearances from that season’s hot rapper. Every musical decision is organic.

The name illustrated their approach. Earlier aliases included 2 Shades Deep and the Misfits—the latter nixed after a teenaged discovery of Glenn Danzig. Both were literal outcasts as new students in the 10th grade at Tri Cities High. Andre skateboarded, wore floral print shirts, and rode BMX bikes. He grew up across the street from the projects, where they watched fights out of the window for fun.

Big Boi soaked up a country influence during his early years in Savannah. In high school, he maintained a 3.68 grade point average and a secret Kate Bush obsession. Most of their classmates bumped bass music. When they auditioned for Rico Wade, they freestyled for eight minutes over the instrumental to Tribe’s “Scenario”.

During an era when artists were expected to choose sides, OutKast opted out of false binaries. They’re haunted by flashbacks of injustice while rolling in Eldorados through East Point. But they realize that it’s more honest to confront your past than run away from it. The slang, finger waves, and Mo-Joe’s chicken wings were in their DNA. So were UGK, 8Ball & MJG, and the Rap-A-Lot artists who first gave a voice to the South. Not to mention the entire Dungeon Family, whose influence on OutKast is unrivaled.

Southernplayalisticadalicmusik was the coming of age story of two baby-faced hustlers puffing and pimping in Adidas and Khakis. Organized Noize’s greasy Muscle Shoals funk, 808 booty-bass drums, and grimy East Coast SP-1200 slaps wrote the template for every dirty south rap album with aspirations of being soulful.

When OutKast called themselves “ATLiens,” it was a partial rupture. They set themselves apart from their city and species—weird storms in the wrong season. But they also identify with the soil and struggle. They are black men in the South, where Confederate ghosts and rebel flags are constant shadows. As they lament on Southernplayalistic’s “Git Up, Get Out”, no one’s running for office but “crackers.” Yet the song’s message is deceptively traditional: Quit smoking your life away, pay attention to your parents, rely only on yourself.

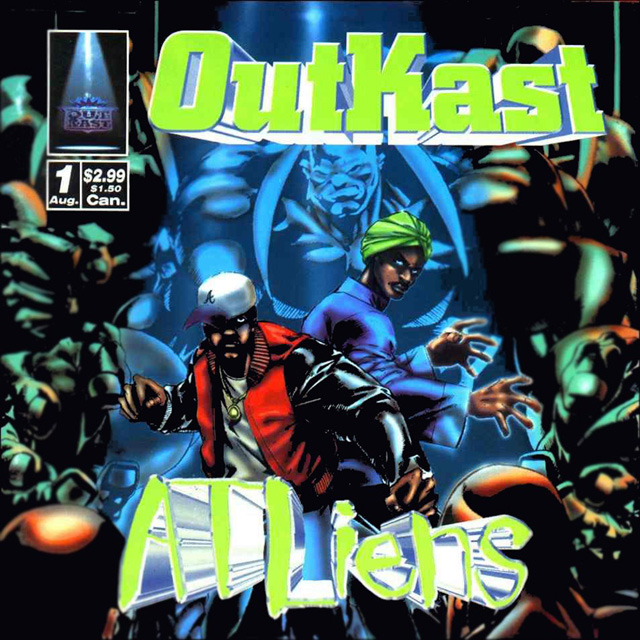

ATLiens was the act of levitation. Every time you look in the sky, they’re back in the Dungeon, staring at ceiling fans searching for inspiration. When you search for them in the Dungeon, they’re at the mall getting harassed by hyena-like fanboys. They dip from outer space to honor everyone from their Atlanta bass predecessors to Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash. After all, everyone liked Kraftwerk.

The last song on 1996’s ATLiens is called “13th Floor/Growing Old”. It’s a hymnal, a sermon against avarice and sin, a confessional, a declaration of black solidarity and southern pride—a meditation on the transience of existence. It’s a psalm for those still searching: church music that’s been secularized, cosmic dub, gospel music given an extraterrestrial groove. Then the scratches hit you: “Ninety-six gonna be that year.” This is hip-hop.

Most rap albums are rooted in some mixture of the present and the past. ATLiens hovers over both—with one eye wired to the future. It explores catacomb thoughts at 3 a.m.: mortality, exclusion, spirituality, consequences, and the desire to transcend. It’s mournful and ethereal, but still street. It expanded what rappers could talk about and how it could sound. If OutKast were going to take the pulpit, they needed a church to preach in.

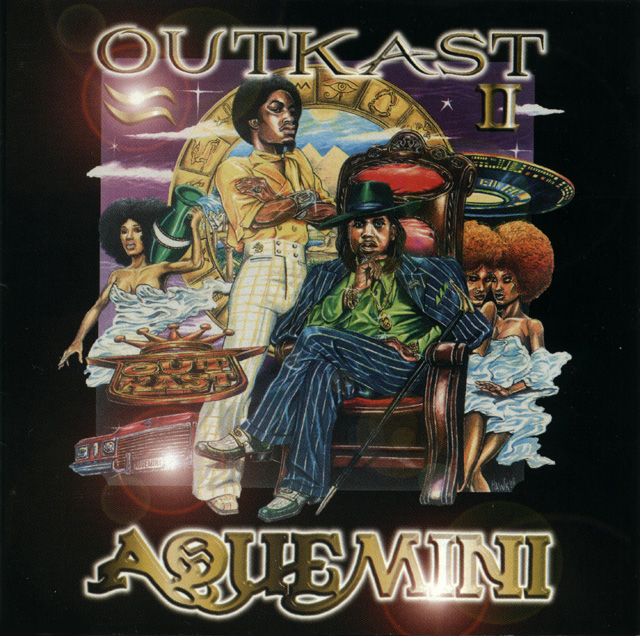

First they were pimps. Then they were aliens or genies. Then no one knew what to call them. The Aquemini liner notes capture Andre adorned in a platinum glamour wig, bumblebee yellow jersey, and sunglasses that ostensibly inspired "Adventure Time". Another shot makes him look like the man in the yellow hat from Curious George leading the Grambling Marching Band.

All doubts were crushed on the album’s first raps. Snapping on those who get the “wrong impression of expression,” Andre shuts up whispers about whether he’s on drugs or gay. Rap had seen afro-futurist eccentrics before, but since hard-core hit in ’94, no one but Kool Keith had dressed so flamboyantly. (And even Keith disguised himself as Dr. Octagon or Black Elvis.)

Andre had reached that rarefied level of “I don't give a fuck” that Kanye West has frantically sought since his first Givenchy kilt. His clothes weren’t a bug-out costume or artistic pose; they felt as creatively surreal as the music. No one on earth or Alpha Centauri could have convincingly pulled them off. Ask Fonzworth Bentley.

The penultimate song on Aquemini is a nearly nine-minute underwater spiritual called “Liberation”. Guests include Cee-Lo, Erykah Badu, and Dungeon Family high priest Big Rube. Like the album itself, it is many things at once. It’s a psychic liberation from genre, expectations, and lingering shreds of convention. It is a manifesto of self-determination, free expression, and a requiem for the enslaved. It is funk. It is soul. It is hip-hop. It is gospel. It is swamp jazz, the blues, and remnants of oral tradition. Voodoo. It’s OutKast, astrologically intertwined and fully emancipated.

Consensus generally favors Andre over Big Boi. This is a fatal misunderstanding of their partnership. If Andre steered more than half the journey on the first two records, Big Boi caught up by Aquemini. His flow is as liquid and low to the ground as a busted fire hydrant. Several hooks, including “Rosa Parks”, belong to him. If Andre is the interstellar satellite, Big Boi is the spy on the streets. The wildest indulgences have checks and balances. You need Big Boi to have Andre. The poet and the player was the tagline; the truth is that you never knew who was who.

Aquemini is a declaration of total freedom without taking your toes out of the soil. Nearly every member of the Dungeon Family contributes memorably, but OutKast assumed more creative control than ever before. Andre started making beats, playing Kalimba, and recruiting gifted session musicians from around Atlanta. (The hoedown harmonica sizzle on “Rosa Parks” belongs to his step-dad, the Reverend Robert Hodo.) George Clinton appears on a song that sounds like it was written for a Terry Gilliam adaptation of Brave New World.

It’s a capsule of a time, place, and movement, but never feels dated. No hip-hop album before or since blended such rich musicality with artful narrative. When Andre opens “Da Art of Storytellin’ (Part 2)” with a storm warning, the beat and vocal effects batter like a hurricane. “SpottieOttieDopaliscious” sounds as sentimental and drunk as the narrator engulfed in Old E, who never made it to the disco door. Samples are sparse. It’s not old music being re-interpreted; it’s old ideas being reincarnated.

During the late 90s, rap typically gravitated towards either austerity or excess. Aquemini matched neither category. “Skew it on the Bar-B” is as lean as an ostrich. “Nathaniel” is a 70-second rap dialed-in from jail—just long enough to acknowledge those still waiting to be set free. Half the songs snake past five minutes. No single cracked the Top 40, yet the album went double platinum.

Released on the same day—September 29, 1998—as albums from Jay-Z, A Tribe Called Quest, and Black Star, OutKast earned the highest praise. The Source instantly canonized Aquemini with the first perfect score ever given to a Southern rap act. That fact might feel like a footnote 15 years later, but at the time, it was a coronation. (I’ll never forget a guy on my high school basketball team in Los Angeles buying the magazine and screaming outside the gym like a town crier: “OUTKAST GOT FIVE MICS IN THE SOURCE!!!!”) They opened the door for the entire region. If you listen to OutKast’s last words on Aquemini, you'll hear a familiar phrase: “The South got something to say.”

Stankonia. The studio name seems like an afro-futurist Xanadu. Between their third and fourth albums, OutKast acquired and re-blessed Bobby Brown’s “Bosstown” in downtown Atlanta. The former house of “Humpin' Around” became hip-hop’s Electric Ladyland, Paisley Park, or Abbey Road—a place where merely invoking the name inspires psychedelic shades and astral sounds.

You’d think that starting your album with the chanted hook, “burn muthafucka, burn American dream,” would do little to endear you to the American record buying public. Political rap had been commercial kryptonite since Ice Cube first met Smokey. But Stankonia transformed OutKast from Southern vanguards into the most universally beloved rappers in the world. They crossed over from "MTV Jams" to triple-platinum "TRL" staples. They won two Grammys. They became the token group worshipped by people who hated hip-hop “except for...”

OutKast mastered the art of sending mixed messages. They tell you that hip-hop is more than just guns and alcohol—but admit that it’s that too. Buried beneath the sweet contrition of #1 single “Ms. Jackson” is the sad disintegration of love and a child caught in the crossfire. Stankonia might initially channel Public Enemy, but it quickly shifts into “So Fresh, So Clean”, a blue tuxedo-soul ode to gator belts, patty melts, and Monte Carlos. Official remixes followed from Fatboy Slim and Snoop Dogg. Andre even shouted out his love of drum and bass in interviews. The evidence is “B.O.B.”, the only song murderous enough to one-up England’s the Prodigy and appeal to fans of Prodigy from Queensbridge.

The back-and-forth between hip-hop and dance music had existed since Chic’s “Good Times” became “Rapper’s Delight”, but during the early 00s, the genre was in a particularly insular zone. A generation emerged with few musical reference points outside of rap. When Stankonia won the Best Rap Album Grammy in 2002, it beat out Ja Rule, Eve, and Ludacris (and, to be fair, Jay-Z’s The Blueprint). The victory was a reminder of how far out the groove could extend.

The civil war had shifted from East vs. West to underground vs. commercial. OutKast might have shared the subterranean allergy towards pop concessions, but they rejected ideology or false purity. You can make a great rap album using only four tracks; OutKast were using all 88 and knew the difference. Andre described it best when he said, "We’re in the age of keeping it real, but we’re trying to keep it surreal."

But even surrealism needs the occasional contrast. OutKast clocked substantial hours in outer space, but still made time to check back in on the block. Despite the rainbow funk jams and Purple One falsetto, the album also introduced Killer Mike and explained why you should never let gold diggers order strawberry lemonade and popcorn shrimp at the Cheesecake Factory. There are skits about prenuptial agreements. “Toilet Tisha” loosely resembles Prince re-imagining “Brenda’s Got a Baby”.

In hindsight, you can see the beginning of the creative rifts. The pair traveled separately. Many of Andre’s beats started with him riffing on an acoustic guitar at home. And judging by the amount of abstraction and aqueous funk jams, you can generally figure out what is a Big Boi idea and what is an Andre 3000 one. Stankonia is OutKast at their most experimental, meandering, and free. It is rap’s White Album. No idea is too bizarre. Each song could spark its own sub-genre—if you even knew where to begin.

Samuel L. Jackson introduced OutKast as “the music of inclusion” at the 2004 Grammys, but Big Boi and Andre didn’t perform together. Instead, Big Boi crooned his #1 single “The Way You Move” backed by Earth, Wind & Fire as part of a funk tribute, and Andre closed out the show with his own #1 single, “Hey Ya”. He wore a fringed neon green jumpsuit, green headband, silver boots, and displayed copious nipple. There were back-up dancers, explosions, a marching band, and massive rapture. No boos occurred until the next day, when Native American activists publicly demanded an apology from Andre and CBS for perpetuating stereotypes. Jimi Hendrix’s estate let the homage slide. After all, the proper context was evident.

Speakerboxxx/The Love Below took home three Grammy’s that night. During their winner’s speech for Album of the Year, Andre interrupted himself to tell the crowd that Stankonia wasn’t their first album. “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik,” he said, repeating it twice to let it sink in.

Nine years had elapsed since the Source Awards. Biggie and 2Pac had become rap’s martyred saints. Suge Knight was incarcerated. Snoop Dogg had signed and left the South’s No Limit Records and his biggest hit that year was “Drop It Like It’s Hot”, with a beat courtesy of Virginia’s Neptunes. Bad Boy generally amounted to Puffy commanding “da band” to fetch him cheesecake. While New York’s biggest star, 50 Cent, was propelled by Dr. Dre’s production and a sing-song flow lifted from Southern rap.

OutKast had not only become the most successful rap group of all-time, they were the biggest band on Earth. The Love Below/Speakerboxxx sold 11 million copies and swept almost every critic’s poll. There are people who think the Beatles are too sappy. Prince is too weird. Radiohead is too icy. James Brown wore everything a little too tight. But everyone agrees on OutKast. At their peak, the duo’s popularity rivaled income tax refunds, cute puppies, and free samples.

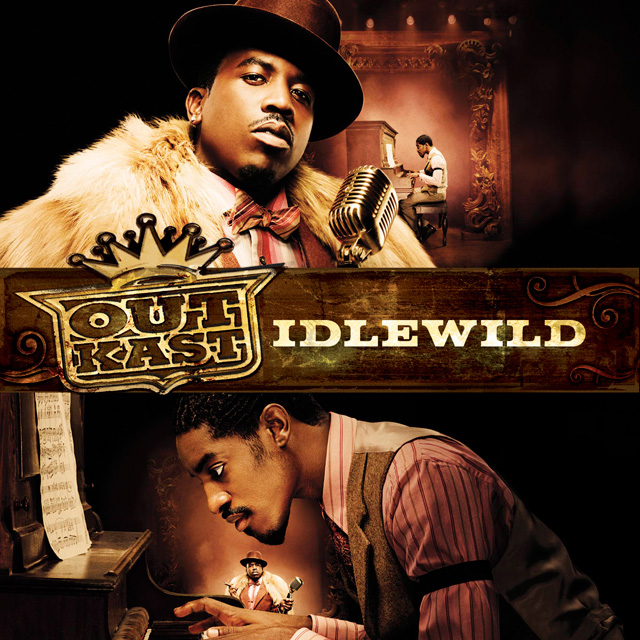

The last official OutKast album was 2006’s Idlewild, which doubled as a soundtrack to the much-delayed film of the same name. There are experiments with blues, vaudeville, marching bands, and Lil Wayne—who had eclipsed the mostly inactive group as the Southern standard-bearer. The album essentially amounts to a bonus track tacked onto the end of their union.

You can spot their influence across contemporary music: Kendrick Lamar, Cee-Lo, Curren$y, B.o.B., Big K.R.I.T., Janelle Monáe, even Tyler, the Creator. Andre defined the idea of the eccentric genius for a generation. Yet OutKast is inimitable. There is no blueprint or trail of crumbs. You listen to their records and wonder how they did it. It’s like visiting the pyramids and concluding that they had to be the handiwork of aliens.

Roughly twice a year, Andre or Big Boi gives an interview that journalists and fans tout as evidence of a future OutKast album. The rumors are inevitably and quickly crushed. Andre remains free to star in shaving-cream campaigns and vent on the occasional guest verse. Big Boi releases solo albums and tours the country, the janissary to their memory, still spitting Southern player raps over saxophone funk.

But even though they haven’t made music in a decade, they didn’t break up. They still represent what they stood for. There is no acrimony or sad cash-in reunion tours. We remember them the way we remember those who died at their peak: permanently immortal, practically perfect. They had managed to say it all.

Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik (1994)

By Nate Patrin

Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik didn't necessarily invent Southern rap or the Atlanta sound. It did define an early strain of it, though, which is accomplishment enough for a debut held down by a couple of teenagers who'd just met two years before. That's with the benefit of hindsight; it's a little hard to hear OutKast's first record with fresh ears, knowing what came afterwards. But note that Southernplayalistic is a freshman effort where even the skits are worth preserving, and try to remember the last time anybody was this good at anything when they hadn't even hit their 20s yet.

This is a record where three largely unknown quantities had yet to be proven: OutKast themselves, the Organized Noize production team, and Atlanta as a hip-hop scene with a recognizably unique identity. That last goal—to diversify the influence of the Miami-derived bass scene and create a wider picture of Southern culture beyond what Arrested Development and Kris Kross were doing—put the musicians in a position that, on record, feels easy to meet. Big Boi and Andre 3000 let their drawls ride out, already having mastered the early phases of their respective styles using immaculately-timed beat-counterpoint flows and abrupt, electric mid-verse runs of rapidfire syllables. Meanwhile, the production took the 808 kicks and blips of bass music and made them the base of a dense, heavy, live-band sound that drew off the traditions of 70s soul; it resonated as familiar to heads who recognized those same waypoints from Dr. Dre's G-funk or RZA's Hi/Stax-chopping minimalism but brought it closer to the source in both means and soil.

Most of all, this album is an introductory lyrical snapshot of an Atlanta viewed with skepticism or curiosity, where you're welcomed to the city and its black way of life by an airplane captain who makes a point of noting that they still fly the Confederate battle flag over the Georgia Dome. The title track is ripe with tangible details: soul food metaphors, Big Boi's neighborhood references to East Point and College Park's “hemp-smoke style,” and the repeated invocations of Atlanta as a blue-skied, sun-baked home to nothing but pimps. But those defining home-turf representations are coupled with something more complicated.

From the get-go, OutKast were caught in a coming-of-age narrative, where they acted the parts of always-strapped hustlers on one hand and young men striving to be better people on the other. It wasn't an uncommon dichotomy in hip-hop, but the tone they used—anxious, frustrated, confused, staring down the future—had rarely felt so unburdened by ego. Andre's rep as the less player-leaning lyricist would grow later on, but even here ambivalence runs through his threats; when he talks shop with a Beretta on “Ain't No Thang”—“one is in the air and one is the chamber, y'all ask me what the fuck I'm doin, I'm releasin' anger”—he sounds more like someone backed into a corner than an instigator. And Big Boi's hustler credentials are driven by someone who feels like he's always been out of options, where a line like “born and raised as a pimp” on “Claimin' True” echoes as much as fate as a point of pride; as he vents against the “D-E-V-I-L” on “D.E.E.P.” there's echoes of a militant hidden beneath the player. When OutKast have crews to represent, they appear as similarly afflicted allies: Goodie Mob make their first album appearance on Southernplayalistic, and their presence feels as much like a chorus of consciences as a group of cohorts. Cee-Lo and Big Gipp's verses on “Git Up, Get Out” are powerful performances in themselves, but they also make that struggle to survive feel bigger than just a handful of individuals.

ATLiens (1996)

By Jayson Greene

When ATLiens came out in 1996, everything had changed for Andre Benjamin and Antwan Patton. Southernplayalisticadillacmusik had turned them from aspiring-rapper kids on the verge of being let down softly by their mentor Rico Wade to actual rappers, ones who had done things like fly with Puff Daddy on a private plane to Howard University to open for Biggie Smalls. The hip-hop media began to cautiously examine and approve of them: In a lead review in the The Source, Rob Marriott bemoaned "the all-out assfest that has become southern hip-hop's defining image" before positioning OutKast as "the antidote" and awarding Southernplayalistic four-and-a-half mics. It was complicated, reductive praise, but it was praise nonetheless, and it shifted the conversation around them. They were ambassadors now—or mascots, depending on how glumly you looked at it.

And on ATLiens, they sounded pretty glum. The album's theme might have been space travel, from the opening "Greetings, Earthlings" to the sci-fi comic in the CD booklet, written by Big Rube. But there is nothing weightless about ATLiens, the moodiest OutKast record. The dominant emotion is white-knuckled and careful, like they were managing an actual NASA launch and had to exert every effort to make sure they weren't incinerated. "Softly, as if I play piano in the dark/ I learn to channel my anger, not to embark," Dre raps on the title track, his voice pinched. "My face is balled up 'cause I ain't in a happy mood," he spits on "Two Dope Boyz". You can hear a contained panic simmering in the lyrics, a determination to escape their surroundings laced with a growing fear that all escape pods have been deployed.

ATLiens is a classic OutKast album, but it's also a bit of a little brother in their story, perhaps because of its doleful countenance. There is almost no uncomplicated fun to be had, and Dre and Big Boi were growing almost comically stern in their boasts: Dre compares his flow to "cod liver oil" on "Wheelz of Steel", while Big Boi calls himself "the lyrical cleansing nuisance" on "Millennium". On "Two Dope Boyz", Big Boi is at pains to clarify that he only rhymes "to prove a point." OutKast would go on to be anguished, soulful, sad, enraged; ATLiens is maybe the only time they sounded this angsty.

If the lyrics tensed, the music exhaled, calmly pointing to new directions. The album opens with chamber pop, jazz flute, and a quote from “Summer in the City” on “You May Die”; Organized Noize produced 10 of the album’s 15 tracks, but ATLiens also marks the point when OutKast became producers. The farsighted Andre had taken the small pile of cash they'd amassed from "Player's Ball" and bought himself a state-of-the-art home studio—an MPC3000, an ASR-10 synthesizer, a Tascam mixing board, and a drum machine. Buying gear doesn't magically make you a producer, of course, but Andre and Antwan sat down thoughtfully at this new equipment and turned out, among other things, "Elevators (Me & You)", their biggest hit yet and one of the most indelible beats in hip-hop history.

With that one quietly unearthly song, they expanded the possibilities for themselves in a way that can only be accomplished with pure sound. Andre assembled the track and Big Boi wrote the hook, and the result hit on a mixture of glowing and exultant, friendly and coolly mysterious. It is a feeling you can't imagine living without once you've experienced it, one that preserves its power played on earbuds walking in the snow or booming out of a car in a summer parking lot. Their other productions on the album moved in different directions: The rippling, textured "E.T.", which features no drums and moves more like a piece of musique concrete than southern hip-hop; “Wheelz of Steel”, which channeled Wu-Tang gloom, cut-up with furious scratching from Organized Noize’s Mr. DJ; the gnarled funk of the title track. But "Elevators" is the album's heart and nerve center. Rappers still turn to the track when they need to tap into that inscrutable feeling, one that hasn't been duplicated or even approximated by anyone since. It was the clearest indication on ATLiens that Antwan and Andre were bound to reach orbit. On their next record, they did.

Aquemini (1998)

By Mike Powell

By 1998, OutKast had two platinum selling-records and a decent amount of critical adulation, but still struggled to get what most artists crave most: respect. Listeners who were drawn to the street stories of Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik pushed away the science fictions of ATLiens, and Andre 3000—once reliably thuggish in a baseball jersey and jeans—experimented with bowties and white linen, an offense more damning in a conservative and often homophobic rap community than any lyric he could’ve dreamed of. “You have to be a strong nigga to take that ridicule,” he told The Source that year.

By the time Aquemini came out, OutKast had explored the temporary promises of materialism and the supposedly more lasting ones of spirituality. Each new answer turned out to be as weak and corruptible as the last. “When you rap and say anything kinda conscious, all the conscious people approach you,” Dre told Creative Loafing in 2010. “After ATLiens I got it all, from books on sex to [metaphysics] and religion. But you also find some of the fakest people with dreads pouring oil on you.”

Disillusionment pushed them to extremes. The harshest moments on Aquemini are more unforgiving than anything they’d recorded before: On “Da Art of Storytellin’ Part 1”, Big Boi doesn’t have time to fuck a girl he meets in the mall because he has to pick up his daughter, so he settles for a blowjob in the parking lot, and—in a voice that stinks of both pride and disgust—rewards the girl with “a Lil’ Will CD and a fuckin’ poster.”

By contrast, its softer moments offer real-world redemption more cathartic and understanding than the distant promises of ATLiens. A verse after Big Boi jizzes in the mall parking lot, we see Dre standing next to a girl on the corner, staring at the stars and talking about what they want to be when they grow up. The girl thinks for a minute, and in the album’s single most startling line, turns to Dre and says “alive.” We later learn it didn’t quite work out that way, but the point has been made: After imagining the paradise of other planets, OutKast had returned to a hard world in which keeping a pulse might be the best you could hope for.

Even Aquemini’s most spirited songs—“Rosa Parks” and “Skew It on the Bar-B”—sound like the combative work of underdogs hungry to be given their fair shake. “Rosa Parks” especially, with its hollering, harmonica-driven bridge, is both the album’s most radio-ready song and its most defiantly regional—not just southern, but country, a mode completely underrepresented in mainstream rap at the time. (Accents don’t get hidden, either: “Tell” becomes tale, “wanna” becomes woanna, and “damn” makes its distinctive metamorphosis into dayum.) When Raekwon shows up on “Skew It”, it’s practically a diplomatic mission: Without him, as he remembers it, the record would’ve never made it to New York.

This goes the album's music, too, which tends toward gospel and southern soul over pure funk or jazz, which favors live-band sounds without making the purist’s mistake of shunning synthetic ones, which is rural in its DNA but refined in execution. Funkadelic is usually cited as a major influence, but the comparison is more useful on Stankonia than Aquemini. Even Funkadelic’s laid-back tracks feel like they’re teetering at the edge of a nightmare. Aquemini—anchored by Preston Crump’s mellow, sustained basslines and the swing-friendly drum tracks of Mr. DJ and Organized Noize—sounds sober and observant, its slow pace less a product of disorganization than of supreme confidence.

Aquemini isn’t fun. Colorful, yes; searching, yes; angry, yes; enchanted by the same phony healers and child-support-dodging deadbeats that it saves its most bitter criticism for, yes—but not fun. It tells me something I want to hear about people: That they make their first mistakes by accident and their second because of a flaw in their design; that their tendency to say one thing and mean another is what makes their life a life instead of an algorithm; and that accepting them ultimately isn’t an act of resignation but compassion.

When Dre and Big Boi made it, they were only 23: Young enough to hope, but old enough to know that hope can sour into cynicism just as easily as it can become love. Or, as Dre puts it on Aquemini’s title track: “Faith is what you make it/ That’s the hardest shit since MC Ren”—testimony from someone at the juncture of looking for answers and realizing that there might not be any.

Stankonia (2000)

By Andrew Nosnitsky

OutKast was always a project about balance. That player and the poet dichotomy was not an exact one when draped directly on the two humans in the group, but it served as a nice shorthand for their collective yin-and-yang dynamic. They wore as many oxymorons as Dre does ascots today: conscious gangstas, retro futurists, pop experimentalists. Stankonia pulls at all of these threads harder than anything they had done previously. It's not the best of their four proper albums by any stretch of the imagination—it might actually be the worst and it's certainly the least consistent—but it's the one that does the most.

Look at the singles alone: "B.O.B.", a violent display of spazzed-out rapping-ass rapping, which cracks the 150 BPM mark (probably qualifying it as the fastest rap hit of all time) and eventually turns into a gospel hymn; "Ms. Jackson", which perfectly condenses the most complicated of human relationships into a four-and-a-half-minute pop song. Then there's "So Fresh So Clean", a reset button back to the Curtis Mayfield pimp funk of their debut. Future/present/past. They bobbed and weaved quickly around this timeline, moving from P-Funk psychedelic guitar solos to trunk punishing 808 kicks and back again. The ideas were ricocheting off one another so quickly that it's hard to even notice when they fail. (We now know that this semi-controlled chaos was partially the side-effect of a break-up already happening in slow motion, but goddamn it was a glorious first step towards implosion.)

In the press surrounding the album's release, Big and (especially) Dre frequently made a point to mention that they had been explicitly avoiding listening to rap music while making the record, but they were clearly reacting to it. Specifically, to the many micro scenes throughout the South that were finally bubbling over into the mainstream after years of local marination. In the mid-90s the nationally visible Southern rappers—OutKast, Geto Boys, UGK, Eightball & MJG—were all products of different cultures, different cities, and different aesthetics, but they had also grown to share certain commonalities. These were acts who tangibly prioritized things like musicality, spirituality, and introspectiveness.

By the turn of the century, the national image of the Southern rapper and the expectations of Southern rappers had begun to morph significantly (check those tongue-in-cheek Pimp Trick Gangsta Clique skits on Aquemini). Labels like New Orleans' No Limit and Cash Money, and Memphis' Hypnotize Minds had regional roots as deep as OutKast's but now they were crossing over nationally with records that were sonically and socially more abrasive than what the Dungeon Family was selling. The beats got thinner, the ideas more blunt.

Stankonia saw OutKast actively pushing back against that tide while simultaneously dipping their toes in the pool. Advance versions of the record, leaked in the golden age of Napster, featured a slightly different mix of "Gangsta Shit", in which a backward-masked voice saying "We have your troops…" was quite audible. At the time, many interpreted this as their formal shot at the reign of the military-minded New Orleans camps—and, presumably, this is why it was buried to the point of inaudibility in the official mix. It wasn't a diss though. Like everything OutKast does, it was complicated: a playful challenge to their successors with that old harder than hard approach.

They warp the emerging image and sounds of the modern down-south d-boy elsewhere on the record: "Call Before I Come" is like Trick Daddy's "Nann" reimagined via Shuggie Otis, complete with an assist from Three 6 Mafia's Gangsta Boo, "Snappin' & Trappin'" echoes the aggression of Memphis, and the Chopped & Screwed coda of "Stank Love" was likely the first time many national listeners would have encountered the Texan style. Even the quasi drum'n'bass madness of "B.O.B." has its roots in the the earliest of "ignorant" Southern rap crossovers—Big Boi has claimed that the aims of the record were to modernize the pace and energy of Miami bass. (Andre's suggested that it was inspired mostly by contemporary rave hopping and the club drugs contained within.)

This is all part of the reason OutKast were able to sustain their credibility even as they got weirder and went pop at the same damn time—they never consciously presented their work as "the other." It was always "we do what you do, but we do it differently." Even in their strangest moments, they never positioned themselves above the trap, just perpendicular to it.

Speakerboxxx/The Love Below (2003)

By Ian Cohen

Every OutKast album title had been a portmanteau, a clashing of words symbolizing a clash of worlds and the volatile union between Andre 3000 and Big Boi. So the backslash in Speakerboxxx/The Love Below was a little pause that spoke volumes, a silent acknowledgment that this was not an OutKast album even though you were being convinced otherwise. The two were barely on speaking terms artistically, but their quasi-solo albums were bound together, both metaphysically and physically. Any discussion of one would include a tacit appraisal of the other, the unspoken competition inherent in any rap duo given an actual playing field. But on a more crass level, you couldn’t choose between Speakerboxxx and The Love Below in a record store. You were buying an OutKast double album or you were buying nothing.

And a lot of people bought Speakerboxxx/The Love Below, both metaphysically and physically: It sat atop the 2003 Pazz & Jop critic’s poll and has sold over 11 million copies. Hard as it is to believe, OutKast had not achieved their commercial nor critical pinnacle with the universally beloved Stankonia. But while “B.O.B.” was a comprehensive survey of genre, “Hey Ya!” hit every demographic imaginable and was richly rewarded—it wasn’t pop, rock, R&B, black, white, young or old, it was one of the last truly universal songs of the iPod era and the reason Gnarls Barkley exist.

Still, it shouldn’t have taken us ten years of hindsight and a cruel dearth of Andre 3000 output to recognize the sheer absurdity of the excitement surrounding an album whose main draw was Andre 3000 not rapping. For all of its supposed adventurousness, The Love Below is not only baldly derivative, but derivative of one source. It’s Andre’s souvenir from Prince Fantasy Camp.

Carnality is seen as a manifestation of spirituality on The Love Below, a rebuke of Andre’s previous assessment from ATLien’s “Babylon”: “They call it horny because it’s devilish.” The Love Below is more or less a concept album about God granting Andre the perfect woman, a reward for being an altogether stand-up dude, except for that one time in Japan (“and head don’t count… aw, I knew you’d understand”). His pitch shifted vocals don’t even bother to distinguish themselves from those of Prince alter ego Camille, and he slops them all over synthesized funk, clumsy jazz, airy “The Cross”-style flanged guitars, and endless canned vamps. And, most crucially, like many latter-day Prince albums, it’s about 95% singing and 5% rapping… and Dre’s singing is about as good as Prince’s rapping. For that reason alone, “Where Are My Panties?” is the second-best song here because it’s actually a skit. And besides “Hey Ya!”, the skits are about the only thing that still holds up on a record that’s lovable but barely listenable most of the time.

All of which makes it a shame that Speakerboxxx was never able to stand on its own. Big Boi’s two subsequent solo albums are of vastly different artistic merit, but suffered the same fate: the endless meddling of label reps and song doctors couldn’t prevent 2010's Sir Lucious Leftfoot and 2012's Vicious Lies & Dangerous Rumors from suffering immediate chart deaths right on the table. Would all of that been necessary had Big Boi capitalized on OutKast’s commercial momentum and a still-healthy record industry in 2003? Or would Speakerboxxx have fared only slightly better than, say, Killer Mike’s Monster or Bubba Sparxxx’s Deliverance?

Speakberboxxx is not perfect, but as a mass appeal hip-hop record, it’s pretty much flawless. Though overshadowed by “Hey Ya!”, is there any doubt “The Way You Move” would’ve been a hit had it been credited to Big Boi rather than OutKast? How could anyone listen to the Afro-electro funk/quiet storm fusion of “Ghetto Musick” compared to Andre’s Lovesexy envy and say Big Boi was the unadventurous one? How could you forget the last great Goodie Mob song ever? How could a song featuring Big Boi, Killer Mike, and Jay-Z get released in 2003 and still be overlooked?

Somehow, Speakerboxxx/The Love Below still benefits from its unique structure—it’s the rare double album that simply cannot be stripped for parts into a cohesive single disc. And while it represents an ionized version of OutKast, the essence remains. You get one of the strongest hip-hop records of the decade and one of the most talented rappers ever going on the sort of non-rap tangent that results in career suicide about 99% of the time. Separated, they may have been hits, but hold the double-CD in your hand and remember: Holy shit, this batshit thing sold 11 million copies and rock critics loved it more than the White Stripes. Granted, the success of Speakerboxxx/The Love Below may owe itself to people who may never buy another hip-hop record. But it was a success all the same, proof there’s no wrong way to do the right thing.

Idlewild (2006)

By Ian Cohen

Perhaps it’s a sign that I need to broaden my social circle, but here’s a list of movies I’ve been able to discuss in depth with my colleagues over the past seven years: Cash Money's Baller Blockin’, Master P's I’m Bout It, Redman and Method Man's How High, Roc-A-Fella's Paper Soldiers and State Property, Three 6 Mafia's Choices: The Movie, and the absolute motherlode, Cam'ron's Killa Season. Yet I might not have a single friend who has seen, or will ever see, Idlewild.

This seems impossible. Unlike the aforementioned, Idlewild is a real Hollywood production and has numerous advantages over your typical vanity movie: It features actors with legitimate acting experience, including Andre 3000 and Big Boi. Beyond that, because OutKast is one of the most popular and beloved musical acts of all time, their movie had a real budget and was released to actual theaters; you didn’t necessarily need to be an OutKast fan to see Idlewild, just someone looking for a way to kill a Friday night. Moreover, it has a plot that’s something other than rappers playing barely fictionalized versions of themselves: Idlewild is exactly like Purple Rain, except OutKast invent rap in a Depression-era speakeasy, and one of them is named Rooster. (I can’t remember which one, though.)

But even if Idlewild the album revealed little about Idlewild the movie, it proved to be a total spoiler, because the actual plot of the film was secondary to the meta-context of making the film: After years of trying to will their dream project into existence, OutKast finally got the greenlight… after they had all but stopped working together. Would Idlewild result in Andre 3000 and Big Boi being OutKast again? Anyone expecting a Hollywood ending could look at the dead center of Idlewild’s tracklist: “Hollywood Divorce”.

The connotation of bitter acrimony from that track is actually somewhat misleading: Idlewild moves with the finality and begrudging purpose of someone cleaning out their old apartment just enough to receive that security deposit. In spite of the strangely thrilling prospect of revisiting the one OutKast album unsullied by over analysis and radio airplay, Idlewild is a punishing listen—or at least karmic payback for the duo’s godlike run of the previous decade. Twenty-five tracks clock in at 77 minutes and yet both of those numbers seem like laughable lowball estimates. For those skeptical of the film, the soundtrack was their worst fears confirmed: a record full of ideas that were clearly sat upon for years and then rushed out with Andre 3000 and Big Boi working with separate agendas but without any of the gleeful experimentation that marked their solo albums.

If someone gushes to you that Idlewild is OutKast’s “weirdest” album, they are likely obsessed and impressed with their own contrarian thinking. Though the experience of listening to Idlewild is certainly weird—it’s still tough to ascertain how OutKast could release a movie and an album in 2006 that completely vanished without making a mark on pop culture in any way whatsoever. You may have forgotten the hungrier guest artists whose performances respected the fact that this is still an OutKast album. Namely, an untamed Killer Mike, an unheralded Janelle Monáe, and Lil Wayne in his Best Rapper Alive mania. But it’s more bizarre to hear OutKast so uninterested in itself, so utterly lacking in invention, so joyless.

There’s as much stylistic breadth on Idlewild as on previous records, but here it’s of the iPod variety: no integration, no Organized Noize, just costumery. At the very least, Andre’s solo excursions are sourced from a wider range than they were on The Love Below, but they're just as derivative: Cab Calloway on “Mighty ‘O’”, “Higher Ground” on “Idlewild Blues”. Idlewild literally ends on “A Bad Note”, eight minutes of migraine inducing “Maggot Brain” mimicry that may have been intended as a joke but felt like a final insult; this is the thanks we get.

For OutKast traditionalists who felt like the praise accorded to The Love Below was a backhanded slight to Big Boi, Idlewild provided some schadenfreude—justice was served, but not in any way that proved meaningful. Big Boi was likely starting to craft Sir Lucious Leftfoot already and while his technical skills are still sharp, he at least had the foresight not to squander his best material here. Instead, on songs like “N2U” and “Peaches”, the libido feels lecherous. Women are either treated as burdens or trophies on these songs and, perhaps to align with the 1930s blues aesthetic of the film, all of them are up to no good. Andre 3000 likewise lets real life trample upon this supposed fantasy construct and brings none of his flower-child levity—he attacks welfare recipients, music critics, Hollywood execs, and basically everyone who questions why he’d do anything other than the one thing he’s better at than anyone else drawing breath on planet Earth: rapping.

As the final excruciating seconds tick off from “A Bad Note”, there’s a comfort in how little OutKast left to the imagination; Idlewild is not generating its legend from never being followed up. In fact, the existence of a track like 2008’s completely inexplicable “Royal Flush”—which had Dre and Big Boi rapping astoundingly well on the same beat—only serves to show just how easily OutKast could reunite and how good they could be. It also shows how easy it is for them to say no.

Dream Tattoo

Dream Tattoo Favorite Cereal

Favorite Cereal

Last Record I Played

Last Record I Played Last Great Book I Read

Last Great Book I Read

Ian Christe; photo by Jimmy Hubbard

Ian Christe; photo by Jimmy Hubbard

Last Record I Listened To

Last Record I Listened To The Last Great Book I Read

The Last Great Book I Read Last Record I Bought

Last Record I Bought

Photos by Matt Arnett or Souls Grown Deep

Photos by Matt Arnett or Souls Grown Deep

Graham Lambkin and Jason Lescalleet; photo by Yuko Zama

Graham Lambkin and Jason Lescalleet; photo by Yuko Zama JANDEK – The Song of Morgan (Corwood) Given the wide range of releases, performances, formats, and instruments in Jandek’s four-decade career, his release of a 9-CD box is not really a shock (nor is its bargain-styled $32 price from

JANDEK – The Song of Morgan (Corwood) Given the wide range of releases, performances, formats, and instruments in Jandek’s four-decade career, his release of a 9-CD box is not really a shock (nor is its bargain-styled $32 price from  WILLIAM PARKER – Wood Flute Songs (Aum Fidelity) Bassist, composer, and bandleader William Parker views his music as part of something he calls “the tone world.” His description of that realm in the liner notes to

WILLIAM PARKER – Wood Flute Songs (Aum Fidelity) Bassist, composer, and bandleader William Parker views his music as part of something he calls “the tone world.” His description of that realm in the liner notes to  NATURAL SNOW BUILDINGS - Daughter of Darkness (BaDaBing) French duo Natural Snow Buildings, who I

NATURAL SNOW BUILDINGS - Daughter of Darkness (BaDaBing) French duo Natural Snow Buildings, who I  GRAHAM LAMBKIN & JASON LESCALLEET - Photographs (Erstwhile) At first glance,

GRAHAM LAMBKIN & JASON LESCALLEET - Photographs (Erstwhile) At first glance,  TOR LUNDVALL - Structures & Solitude (Dais) I’m breaking my own rule by including

TOR LUNDVALL - Structures & Solitude (Dais) I’m breaking my own rule by including  Photos by Vanessa DeVico

Photos by Vanessa DeVico

Donny Osmond: "Sweet and Innocent"

Donny Osmond: "Sweet and Innocent"

Various Artists: Annie (Original Broadway Cast Recording)

Various Artists: Annie (Original Broadway Cast Recording)

The Itals: Give Me Power!

The Itals: Give Me Power!

Nazz: "Open My Eyes" (1968)

Nazz: "Open My Eyes" (1968) Halfnelson:

Halfnelson:  Todd Rundgren: "Hello It's Me" (1972)

Todd Rundgren: "Hello It's Me" (1972) Todd Rundgren:

Todd Rundgren:

Utopia:

Utopia:  Meat Loaf:

Meat Loaf:

Todd Rundgren:

Todd Rundgren:

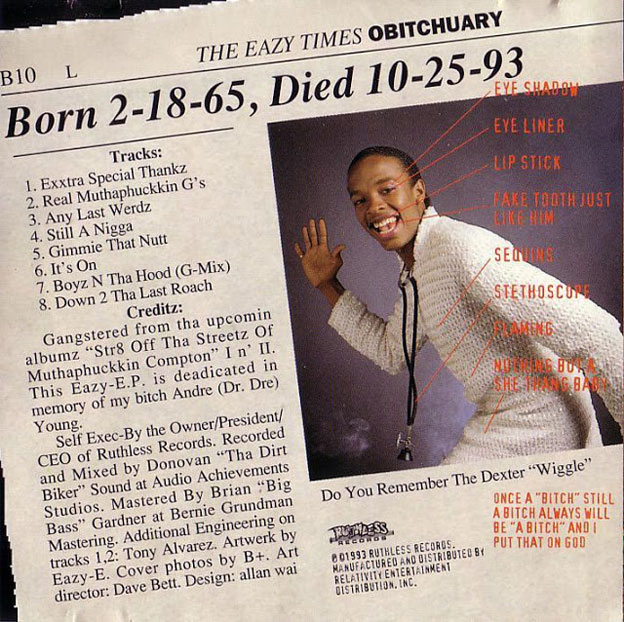

Chris “Broadway” Romero working on a virtual Ol' Dirty Bastard

Chris “Broadway” Romero working on a virtual Ol' Dirty Bastard Romero

Romero A digital rendering of Eazy-E

A digital rendering of Eazy-E Romero in his space at Play Gig-It

Romero in his space at Play Gig-It

Roland TR-808

Roland TR-808 Oberheim DMX

Oberheim DMX Roland CompuRhythm CR-8000

Roland CompuRhythm CR-8000 Vox Percussion King

Vox Percussion King Roland TR-909

Roland TR-909

The Ohio Players: Honey

The Ohio Players: Honey Egyptian Lover:

Egyptian Lover:

Leon Ware: Musical Massage

Leon Ware: Musical Massage