Rising: Kraus Makes Noise Rock for Anxious People

Longform: Save the Last Dance: The Fight for London Club Culture

The endangered Corsica Studios crouches under the railway arches of Elephant and Castle Station, a clubbers’ hideaway in southeast London. The neighboring district lays low on weekday evenings, populated by commuter traffic, bored teens, and the occasional clan of city boys ambling by from a pub on the roundabout. But when I arrive one Tuesday in the fall, the DIY performance space is aglow. Inside, gloriously profane rapper Princess Nokia is inciting a riot amongst art students in chokers and drawstring backpacks, tropical shirts and sports shorts. “Children, are you having fucking fun?” she enquires, as purple spotlights dance in the fog. The couple hundred in attendance scream their approval.

At midnight, friendly clusters split into squadrons of solo dancers, carving out space with fluid hips and fast limbs. As the DJ’s baile-funk rhythms swell, a succession of women twerk and belly-dance onstage. Beside me, a man and woman suddenly become entangled, hands delving as they back onto a carpet of crumpled craft beer cans. An hour later, everyone streams through the exit and past a series of billboards on the backstreet. The glimmering triptych of signs, streetlamp-lit and mounted on construction fencing, herald a multi-billion pound makeover for Elephant and Castle, including a handsome new housing project opposite Corsica. For clubbers, the corporate enthusiasm tells a familiar story: One of London’s last surviving underground clubs now stands next to the most ambitious renewal project in the capital.

“There’s a sense that we’re being surrounded—and there’s probably stuff going on behind the scenes that none of us are aware of,” Corsica’s Adrian Jones tells me, leaning into a table in the club’s operations room. Hanging over his head is a nebulous social vision determined by councillors, developers, and inflating rents. In the last 10 years, London has lost roughly 50 percent of its nightclubs, many due to developments like the housing project opposite Corsica. In typical cases, developers locate underfunded areas set for “activation”—that is, glamorized to prospective residents by lifestyle industries, particularly nightlife. But the social good of extra homes is undermined by shady deals between developers and local governments.

Thanks to government cuts, local councils such as Southwark’s—whose remit includes the Elephant and Castle district—are under-resourced and notoriously pliable. In rebuilding the Heygate Estate opposite Corsica, developer Lend Lease convinced councillors that the project required a 94 percent cut in apartments for “social housing”—the category of cheap homes reserved for those most in need—compared to the project demolished to clear its path. Such schemes have been described as class-cleansing, with low-income residents displaced to remote boroughs while wealth fills the luxury flats. Rents shoot up, as do business rates for clubs. Councils juggle new tenants’ demands with the borough’s existing nightlife ecosystem. When in doubt, they prioritize residents, and clubs vanish.

“I don’t want young and creative Londoners abandoning our city to head to Amsterdam, to Berlin, to Prague, where clubs are supported and allowed to flourish,” Sadiq Khan, London’s new centrist mayor, announced on the campaign trail last spring. His basic plan, based on a rescue document for London venues commissioned by his predecessor, Boris Johnson, is now in place: As well as opening 24-hour tube lines, Khan has pledged to implement the Agent of Change principle, which stops residents challenging noise that predates their arrival. In LGBT advocate Amy Lamé, he’s also appointed a new “night tsar”—a title contrived to swerve the “night mayor”/“nightmare” homonym—who will work alongside a new Night Time Commission to represent the night economy. Contributors to that economy are still skeptical, though.

“What worries me is nothing’s being done fast enough,” Four Tet’s Kieran Hebden, who Khan has invited to discuss nightlife at City Hall, tells me. “We’re gonna lose everything, and then everyone’s gonna wake up and be like, ‘Oh well, we don’t have any nightlife, we should try and build some up now.’ That doesn’t come out of nowhere—it takes years.”

Benji B, a stalwart club DJ and BBC Radio 1 presenter, says London clubs have incubated a “particle collision” of dance styles in recent years, producing vanguard work by the likes of Floating Points, Joy Orbison, and the Hyperdub label. It’s these established spaces, Benji and Hebden argue, that foster London’s diverse subcultures. “When people use a space creatively, there’s an invisible impression that’s left behind,” Corsica’s Amanda Moss says. “You can’t see it, but you can feel it.”

“We’re gonna lose everything, and then everyone’s gonna be like, ‘We don’t have any nightlife, we should try and build some up now.’ But that doesn’t come out of nowhere—it takes years.”Four Tet’s Kieran Hebden

The predicament facing London nightlife dates back to the turn of the millennium. By then, rave had long since returned from the countryside, shepherded into regulatable venues by the 1994 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, which clamped down on outdoor parties and the attendant mood of national anarchy. In the capital, superstar DJs like Paul Oakenfold and Sasha commanded enormous crowds (and fees) filling superclubs like Ministry of Sound and Home. Metalheadz, Goldie’s drum’n’bass night at the Blue Note in Shoreditch, became an incubator for forward sounds. “That period of innovation is unparalleled in my experience of clubbing,” Benji B attests.

But the big-club boom was a bubble, and by 2002, DJs were declaring an end to the superclub era. This was a transitional period for nightlife: The 2003 Licensing Act gave pubs permission to set up dancefloors, hire functional DJs, and stay open until 2 a.m. Their gain was a major loss for clubs, whose captive market when pubs closed at 11:30 p.m. disintegrated overnight. It didn’t help that barely any London councils supported the act’s other revolutionary factor: the possibility of 24-hour licenses for clubs.

Regardless, as the superclubs fell, new midsize spaces and warehouse parties rushed into the void. After cutting his teeth at superclub the End in the mid-2000s, Hebden turned his attention to a poky new sacred space called Plastic People. Over a two-year residency, he developed Four Tet’s club-focussed 2010 album, There Is Love in You, breaking out of a creative rut in the process. “I was making records to play in that club, to play to that audience,” says Hebden.

Plastic People remained supportive even when only a few dozen fans were turning up—for Hebden, but also, crucially, for pioneering experimental nights. With FWD>>, where DJs such as Skream and Youngsta advanced dubstep before the term was synonymous with big-tent EDM, Plastic People earned a reputation as “the last bastion of credible club culture” in rapidly gentrifying Shoreditch, Benji B tells me.

In 2010, the club survived a license review, but 2015 saw new restrictions on alcohol sales and opening hours hasten its closure; although the club denies developer pressure, Benji believes authorities meted out harsh licensing rules because planners wanted the space. “There were people getting ambulanced out of the bar [across the road] and having their stomachs pumped in the street,” he says. “And yet the one safest and most mellow and music-dedicated space—with the friendliest, non-druggy, non-dangerous crowd in the whole of Shoreditch—was the place that the council attacked the most.”

In the early ’80s, a poignant mission statement printed on flyers for the legendary Manchester club The Haçienda read: “To restore a sense of place.” The line remains a pithy summary of the challenge facing Sadiq Khan and London’s save nightlife initiatives—but now it’s the sort of doublespeak familiar from signs promoting new developments, on which every erected high-rise is heralded as a gift of utopian vision. As PR wars rage around London real estate, nightclubs have become symbolic battlegrounds for the future identity of London. And no club has been more tightly entangled in that battle than Fabric.

Since opening in 1999, Fabric has survived rampant gentrification, encroaching pseudo-nightclubs, and the epidemic of superclub closures. Founders Keith Reilly and Cameron Leslie set their stall by rejecting superclub status, snubbing bold-name DJs to promote diverse bookings like Asian Underground pioneer Talvin Singh and international crate-digger Gilles Peterson. “It was brilliant, madly exciting, on a bigger scale to other new clubs,” says Hebden, who first attended Fabric in its opening week to see Daft Punk. That same night, he recalls dreamily, he saw Boards of Canada, Autechre, and Roni Size play sets elsewhere around London. “Where’s the equivalent of that now? We’re miles away from it all of a sudden.”

After years of friendly relations, Fabric’s first major clash with police came in 2014, after the club’s fourth drug death in three years. At a review, the Metropolitan Police argued the council should revise Fabric’s license to include a string of tougher measures. The council agreed, but at Fabric’s appeal, the magistrates’ court rescinded two key conditions: ID scanners and sniffer dogs. Speaking to BBC Radio 1 this year, Cameron Leslie said he believes the decision “put some noses out of joint” at the Met, causing them to launch a “vendetta” against Fabric.

Last August, Fabric closed voluntarily after two more ecstasy-related deaths at the club. Sadiq Khan’s office panicked—as emails obtained byMixmag show, the deputy mayor for culture, Justine Simons, worried closure would discredit Khan’s pro-nightlife campaign. But at a hearing in September, the Met stood firm. They insisted there’d been more deaths at Fabric than any other London club. (Leslie has blamed the rise in drug deaths on a “massive increase” in MDMA purity, a claim backed up by the 2016 Global Drugs Survey.) During a string of undercover visits to Fabric, named Operation Lenor after a brand of fabric softener, police observed people “sweating profusely and staring into space,” which they believe implied widespread drug use. The Met argued Fabric was already ignoring conditions—they claim staff overlooked unconcealed drug deals, for instance—so adding additional restrictions wouldn’t help.

Islington police superintendent Nick Davies said that, while he accepts clubs like Fabric will always have drugs, “You can’t honestly think I’m doing my job with six dead bodies that the police do nothing [about].” Reading details of the deaths, one Islington councillor broke down in tears. Committee chair Flora Williamson concluded Fabric had incubated a “culture of drug-taking.” After hours of deliberation, the council revoked the club’s license with immediate effect.

Two weeks after the decision, Fabric advocate Nathalie Wainwright welcomes me to her flat in east London, apologizing for nonexistent mess. A few days earlier, alarmed by the verdict, she had cut short her travels in southeast Asia to join the club’s sizeable resistance. We chat on the mezzanine, sipping Becks as the last daylight bleeds through the windows.

Born in 1983, Wainwright was the second child of middle-class parents. She grew up in North Lincolnshire with her brother, Jean-Marc, a promising artist. At school, she piggybacked on her sibling’s social cachet, despite their nerdy preoccupations: Jean-Marc buried in sketchpads, Nathalie in the ballet studio. “The thing with being a popular kid is you can do what the fuck you like,” Wainwright recalls, smiling, as she taps a Marlboro Gold into an ornate ashtray. “But he wasn’t like a mad painter—he made pen and ink drawings, things like that.” She rolls up her sleeve to reveal a floral tattoo based on one of her brother’s incomplete sketches.

On June 7, 1997, Jean-Marc and his friends descended on a happy hardcore rave at the Zoo, a nightclub in an amusement park roughly an hour’s drive from home. Like his friends, Jean-Marc dropped his pills early and kept going. Nobody is sure what happened in the club, or when Jean-Marc consumed an extra batch, but Wainwright believes, at around 2:30 a.m., he had taken eight pills and “a load of speed.” By that time, his friends were urging venue staff to call an ambulance, because he’d fallen ill after an apparent overdose.

There’d been a similar incident in the Zoo the week before, when Daniel North, a 16-year-old from York, collapsed after taking ecstasy and died 12 hours later. Local police, who had arrested nearly 50 ravers in a previous raid at the club, urged them to tighten health and safety. But the threat from law enforcement proved counterproductive. Wary of the Zoo’s image, staff refused to call an ambulance for Jean-Marc, reassuring his friends he’d recover shortly. Without cell phones, they had little choice but to trust them.

Half an hour later, as a friend cradled him in his arms, Jean-Marc had a seizure, then another. Alarmed, the friend noticed Jean-Marc had swallowed his tongue, which he extracted from his throat. Wainwright says the ambulance took 40 minutes to arrive. By the time he got to the hospital, Jean-Marc had suffered lung failure, which led to blood clotting. His cause of death was fluid on the brain.

Wainwright pins much of the blame for Jean-Marc’s death on the club’s amateurish health and safety protocol. “There’s no way that fluid would’ve developed if he’d been responded to straight away,” she says. “I know it must’ve been really, really bad, because—and I should never have looked but I did—when they returned his stuff to our parents, his jeans were cut all the way up here”—she points up her leg—“and his top was cut all the way up here”—she runs a finger along her stomach and chest, to her throat. “And it was covered in blood.”

While Wainwright fiercely fights for new drug policy, she’s sympathetic to bereaved families who rally against club culture. But she’s also found a community for whom losing loved ones prompted a conversion toward liberal thinking on drugs. Wainwright recently wrote a letter urging politicians to reconsider the Fabric decision, and her own dad offered testimony. “To shut down cultural institutions in the name of families like ours, who have lost loved ones in such a tragic way, is shameful,” he wrote. “You do not do so in our interest, you dishonour the names of those who have tragically lost their lives by no longer providing them with a safe space to enjoy the music and culture they love.”

The Zoo closed days after Jean-Marc’s death. Owner John Woodward, the millionaire behind several caravan and entertainment sites, invited press to photograph him smashing its quirky driftwood sign. The tragedy sparked a local press campaign against ecstasy, which police unquestioningly cast as the villain—despite claims from Jean-Marc’s friends that the club had switched off cold taps to sell bottled water. “Our message to the young people is that you are playing Russian roulette with a 50-chambered gun,” detective inspector Martin Bontoft told one paper. “How many more times do you have to be told about the dangers of the drug? If you take ecstasy you are dicing with death, you are going to die.”

Fabric, which employed two trained medics a night and a respected security firm in Saber, was held up nationally as the gold standard for club management. The club’s diligence could be seen in 2014, when a security guard found a student named Keith Dolling seven times over the limit for recreational MDMA use, with a life-threateningly high body temperature. The club’s medics packed his body with ice, suctioned his airways, monitored oxygen levels, and, when his breath shortened, ventilated him and prepared defibrillators. They couldn’t save Dolling, but the incident forced the Met to acknowledge Fabric’s above-average medical care. “I’m tremendously impressed by that,” senior coroner Mary Hassell told an inquest. “It was really quite advanced care. Care like that gives a person the best chance they could have. ... [It’s] quite extraordinary that a nightclub would have that level of expertise and would be delivering that level of care to the clubbers.”

When I read the report to Wainwright, her eyes widen. “That’s fucking incredible, if you ask me,” she says. “If Jean-Marc had been in Fabric, this would never have happened.”

Wainwright now believes in policies of harm reduction to make drug culture safer. Advocates argue that authorities should accept that drugs aren’t going away and, instead, use methods like drug testing—whereby experts analyze powders and tell you exactly what’s inside—to promote safe practice among users. In 2013, then-Home Secretary Theresa May spoke about the possibility of introducing drug testing in British clubs, after a teenager died at Manchester’s Warehouse Project. May, now prime minister, said, “If somebody has purchased something that the state has deemed illegal, it is not then for the state to go and test it for you.”

While opinions collide over how and where drugs should be tested, nightlife hubs across Europe broadly agree that harm reduction saves lives while zero-tolerance endangers them. “The first obligation of a government is to keep people safe,” Mirik Milan, the Amsterdam night mayor and self-proclaimed “rebel in a suit,” tells me over Skype one afternoon. “I understand people say, ‘It’s illegal so we’re not gonna test it for you,’ but the outcome is that people will do it anyway, and that people are dying.”

With such inconvenient truths in mind, Amsterdam provides daytime drug-testing facilities in labs around the city. In late 2014, when a bad batch of “Superman” pills circulated, Amsterdam caught it and issued a televised warning. There, nobody died; in the UK, only the fourth “Superman”-related death prompted authorities to issue cautions. In the liberal Swiss city of Zurich, where festivals provide on-site drug testing for attendees, seven years have passed without party drug deaths.

Recently, UK charity the Loop, which offers to test drugs for deadly adulterants like PMA, has been installed, experimentally, at Manchester’s Warehouse Project and festivals Secret Garden Party and Kendal Calling. Outside of the Met, which says drug testing sanctions drugs, London authorities have some appetite for such facilities. After Fabric’s license was revoked, Islington Council leader Richard Watts told BBC Radio 1 that front-of-house testing in clubs “would be pretty sensible. As a council, we would consider those kind of approaches. I am personally pretty convinced that the current approach to drug laws isn’t working.”

Berlin perfectly illustrates that drug tolerance and political common sense can revolutionize an ailing club scene. To discuss how, I meet Lutz Leichsenring, a leading nightlife advocate, at a café the German capital’s Mitte district. As his dog Lola runs laps around his ankles, Leichsenring, an affable firebrand, fluently criticizes Britain’s focus on so-called “night time industries.” “It includes a lot of bullshit,” Leichsenring sighs. He argues dedicated clubs define a city’s nightlife identity.

In Berlin, Leichsenring adds, “We just know young people in the music scene take drugs. You don’t want to criminalize people who go into clubs, even if they take drugs—they’re not criminals. We want to make it hard for the criminals to sell them drugs.” When I ask about the chances of security parading sniffer dogs along Berlin club queues, he laughs into his lap.

Berlin’s ascent as a nightlife superpower began after reunification, in 1991. Radical artists and squatters swarmed into abandoned banks, warehouses, power plants, and shopping centers in the East. In 2000, a spate of zealous police raids struck the club scene they’d established. Six nightlife figures allied and formed the Club Commission to protect their culture. Leichsenring, a former promoter and club owner, was elected spokesperson in 2009. “We haven’t had any raids since the Club Commission was founded,” he tells me, “because the police know now that there is a voice—somebody who can work on problems.”

In the face of aggressive gentrification, the commission plugs clubs, local government, and developers into one network. In recent years, they’ve fought planners to preserve club heartlands; linked venues with government culture and planning sectors, via a funding body; and drawn up a map of Berlin music venues, which incoming developers must consult before pitching authorities.

The benefits of that work—enjoyed by the city’s loose workforce of artists, musicians, and other creative freelancers—provide the backbone of Berlin’s unique night culture. Financially stable venues foster experimentation, while reverent clubbers embark on sessions that sprawl across liberal opening hours.

Shanti Celeste is one of many UK-bred DJs who’s upped sticks for Berlin in the last decade. In Bristol, the twenty-something helped put on nights at the Island, a renovated court complex with underground holding cells, where she and a few mates would throw intense parties lasting several hours. But Berlin is different. “Here, there’s so many more clubs to go to, and they open from god knows when until god knows when, so your window to rave your tits off is way bigger and more spread out, which gives you a more relaxed attitude,” she says as we sit in her roomy Neukölln flat. Despite that, Celeste doubts London could adopt the model wholesale. “I don’t know how well 24-hour clubs would do,” she admits, “because it’s a hard place to live. People work 9-to-5. People struggle.”

“There needs to be a bit of edge in life, otherwise there’s no sense of individuality in civilization. It is a question of finding the balance between giving people freedom and protecting people.”Fabric lawyer Philip Kolvin

On November 21, as Fabric’s fundraising campaign hit £320,000 ($390,000), it was announced that pre-hearing negotiations with Islington council had succeeded: In a seemingly unprecedented move, the council reversed Fabric’s license revocation. But while greeted with relief, the agreement—which saved both parties enormous fees—wasn’t quite a fairytale ending. For Fabric, the price of avoiding an appeal was a strict license rewrite they might have defeated in court: ID scanners, lifetime bans for those seeking drugs, new lighting and CCTV on dancefloors, and a raise on the age of entry to 19.

A week after the agreement, Fabric’s lawyer, Philip Kolvin, welcomes me to his office in central London. He wears a suit, jacket open, and speaks with the regal English accent of a ’50s radio newsreader. While he can’t discuss the Fabric negotiations, Kolvin, who recently became chair of Sadiq Khan’s new Night Time Commission, is diplomatic towards the deal’s critics.

Club purists argue that ID scanners are invasive, vulnerable to identity thieves, and terrifying to those with drugs in even trivial quantities. They speculate that lifetime bans will encourage users to swallow pills excessively before coming in; that 18-year-olds will take drugs elsewhere, without Fabric’s gold-standard medical team; and that abundant CCTV turns a club from a pocket of escapism into Big Brother’s venus fly trap.

“I’d hate to think that Fabric set a precedent,” Kolvin admits, after sipping his tea. “I’ve picked up from the blogosphere this idea that you should be able to go to Fabric and express yourself as you want. I’ve still got some sympathy with that—there needs to be a bit of edge in life, otherwise there’s no sense of individuality in civilization. It really is a question of finding the balance between giving people freedom and protecting people.”

I ask whether he thinks Fabric found that balance, or if it was tempting to put the funds towards a full appeal. Kolvin furrows his brow and, with some awkwardness, slides a hand inside his shirt to clasp his shoulder. “Fabric was in a situation where it needed to reopen,” he says finally. “In the perfect world, would that be the prescription? I don’t know. But if somebody’s carried into the emergency room about to die, you can’t scratch over every little thing that happened by way of treatment. They were in an emergency situation.”

At 2 a.m. on January 6, Fabric’s reopening night thunders ahead. Earlier in the day, club co-founder Cameron Leslie told the BBC there was no “pleasure or relief” in the reopening, but punters, it seems, leave their reservations at the heavily staffed door. At one point, hundreds dance under a neon-red “#yousavedfabric” sign as the “Stranger Things” theme mixes into a drum’n’bass salvo. Men part the dancefloor, hoisting up rounds with wobbly hands; the recipients greet them like returning war heroes, all but forgotten in their absence. Strangers offer lone dancers stoic fist bumps, acknowledging their euphoria. Out a side exit, a loose-tongued clique hovers around the club’s new medical tent; beyond it beams the smoking area, which, to pupils attuned to the dark club, appears floodlit.

It’s 2:30 a.m. when I step outside, just as security lead a resigned-looking man and his friend indoors by their arms. Beside me stands Tom, a Fabric patron of 14 years. His friend Dave traveled from Manchester to celebrate the reopening. “It’s a music culture that’s not available anywhere else,” Tom tells me. “Fabric is the pioneer. There’s no club like it.”

Both drug-free, Tom and Dave roll eyes at the suggestion tighter rules will constrain clubbers. Neither seems concerned by the lighting or ID scanners, saying longer queues were tonight’s only quibble. “If you can’t have a good night without drugs, then you’re here for the wrong reasons,” Dave says.

As we speak, a group of 19-year-olds tumbles outside, angling for smokes. One tells me his name is Benny, and I offer some Extra for his hectic jaw. His friends, whose gum was confiscated on entry, eyeball the packet in disbelief, as if I’d produced a handful of magic beans. “I started coming up [on MDMA] in the queue, freaking out,” admits Benny, gratefully taking a piece. “But I didn’t want to risk a lifetime ban.”

This younger clan backs its philosophy—that government drug stigma critically endangers users—with impressive screeds on policy nuances. Animated, they wax lyrical about harm reduction, citing arguments mainstreamed in publicity around Fabric’s closure. “When people drink, they go out to get fucked,” concludes Benny. “We come out to enjoy the music—that’s what it’s all about. We’re a family.” With bowed heads, they drop their cigarette butts and approach the entrance. A faint grime beat emerges from within, and the security guard steps aside, smiling, to permit their return to the night.

Greil Marcus' Real Life Rock Top 10: The Secret of Jack White’s Success

1. and 2. Mats Gustafsson and Christian Marclay, In Hindsight (Vinyl Factory) and Okkyung Lee and Christian Marclay, Amalgam (Northern Spy) Marclay’s work has been so powerfully visual over the last few years—his 24-hour film The Clock, the comic-book inspired Actions aka Onomatopoeia paintings, his sidewalk animations videos—that you can forget he started out as a turntablist in New York art-punk clubs in the early 1980s, sometimes running eight records at a time. These live recordings from two shows at Café Oto in London with the saxophonist Mats Gustafsson (2013) and the cellist Okkyung Lee (2014) are proof Marclay hasn’t lost a step. He’s invented new moves, because he has to.

Gustafsson’s sound is so big and harsh it feels as if he’s shoved Marclay off the stage; with the music chasing the STOMP FOOM FWHAM ZWEE NOOOOHS BLECH words of the Actions paintings (collaged on the sonically blank back side of the In Hindsight 12"), it can take a while to realize that the echo in the music is Marclay scratching his way into the saxophone. With Lee, the excitement again comes when you can’t tell the musicians apart—when Lee separates her own tone at the end of a movement, the pleasure is like the absolutely satisfied relief you feel when a solo ends and the singer takes back the song. What could be a voice could also be a needle drag, a sample, or even the cello itself; you don’t want to decide. This is less of a tour de force than the show with Gustafsson, and far richer: much longer, meandering, teasing out holes and hollows in the cave the musicians seem to be building inside the club they’re playing. On side two, as Lee makes an almost industrial noise—now it’s she who’s scratching, Marclay keeping her time—you could be listening to the Rolling Stones’ “Goin’ Home”: the momentum is that fierce, that free. The music seems to have dropped from a low sky, as if Marclay and Lee caught it and ran, got lost, slowed down, and stopped.

Okkyung Lee & Christian Marclay: "Amalgam" (via Bandcamp)

3.Passengers, directed by Morten Tyldum (Columbia) On a 5,000-passenger spaceship on a 120-year voyage to colonize a planet (Earth having become, among other things, “overpriced”), Chris Pratt wakes up in his hibernation pod. He doesn’t think much about why no one else is waking up, follows computer directions to his cabin, changes into regular clothes, and in the bathroom the piped-in music is playing “Like a Rolling Stone.” It sounds tinny and small, with the band inaudible; it sounds like a folk song, a 78 from the 1920s or the ’30s, with the vocal never sounding more hillbilly, but the muscular rhythmic lifts in the melody are still there, and they still give that complete and subtle thrill. Pratt isn’t really listening, but he catches that; possessed by a spirit of confidence, even bravado, with an unstressed but unmistakable change in the way he carries himself, he steps out of the door and into the plot.

4. Arrival, directed by Denis Villeneuve (Paramount) The alien ships descend around the globe, apparently at random: the best explanation anyone can come up with is that wherever they landed, Sheena Easton once had a hit.

5. A. O. Scott and Manohla Dargis, “Big Statements from Smaller Films,” The New York Times (January 8) One of the Times’ faux critical conversations, which usually seem like a lazy alternative to actually composing something (he writes a statement, emails it, she writes a statement, emails it back)—but with the piece focusing mostly on race, racism, and “unexamined assumptions,” in this case not at all. If Moonlight and The Birth of a Nation and Barbershop: The Next Cut are films about race, Scott asks, why aren’t Manchester by the Sea and La La Land and Sully—and by the way, why does La La Land feature “a white pianist as the savior of jazz and a black musician as its corrupter”? Nothing about Elvis’s birthday, though.

6. Sleater-Kinney, Live in Paris (Sub Pop)“Start Together,” “Jumpers,” “Dig Me Out,” and especially “Turn It On” seem to leap off the stage, but it’s the last number, the light, breezy “Modern Girl,” that makes it all stick. When Carrie Brownstein exhales the line that keeps coming up like someone coming up for air—My whole life—you can hear a whole life. You can hear tiredness, regret, dissatisfaction: a thin sigh of wanting more. Next, in a fan’s world, Covers Live—this band has always been a jukebox. Start with “Rockin’ in the Free World,” go to “White Rabbit,” “Tommy Gun,” “The Promised Land,” “Fortunate Son,” “More Than a Feeling” (from their first recording session, in 1994), end with “Faith,” which along with “Rebel Rebel” closed their San Francisco show on New Year’s Eve—or whatever funeral they cover next, because they’re fans before they’re anything else.

7. Brokeback, Illinois River Valley Blues (Thrill Jockey) Tortoise bassist Doug McCombs has always been more relaxed, more unconcerned, with his instrumental Brokeback side project (vocals by Amalea Tshilds are noted, but the credit ought to read “texture”), and Tortoise is a pretty relaxed and unconcerned band. This starts slowly and it ends that way, a fantasy soundtrack for Once Upon a Time in the West, a western Quentin Tarantino hasn’t made yet, or one of the forthcoming episodes of “Twin Peaks,” or even a Tarnation album without Paula Frazer. It’s music as weather when there really isn’t anything else to talk about. It’s impossible to pick one song over another; if it’s “Cairo Levee” today it’ll be “Spanish Venus” tomorrow. If you’re certain McCombs has found what he’s looking for with “Andalusia, IL,” with “Night Falls on Chillicothe” you hope he never will.

8. Pete Wells, “Making Way for the Tried and True at Cut by Wolfgang Puck,” The New York Times (December 20) On entering: “It’s how you’d imagine a sexy downtown bar if you’d never been downtown, gone to a bar or had sex.

9. Why Jack White Has So Much Money (College Football Playoff National Championship, Alabama v. Clemson, ESPN, January 9) Because a snatch of a martial-anthem trumpets-and-tubas version of “Seven Nation Army” is used between every pause, between plays, at time outs, with what sounds like an instant of the real thing to introduce every commentary, to signal every commercial. In the course of a single game, hundreds of times.

10. Bob Dylan, “Once Upon a Time,” in Tony Bennett Celebrates 90: The Best Is Yet to Come (NBC, December 20) After Lady Gaga, Elton John, Stevie Wonder, k.d. lang, and nearly countless more, it was the last performance before Bennett’s solo final: a no-happy-ending song recorded by Bennett in 1962. There were notes Dylan couldn’t hit—as the song was written, but not as he thought it through, felt it out, sang it. He used the mike stand as a kind of mast, or harpoon: shifting it from one side to the other, moving it higher or lower, he dramatized all the unknown directions a song beginning Once upon a time might take. He made the song interesting, unsettled—“He made it about America,” said one person watching.

Lists & Guides: The 50 Best IDM Albums of All Time

PARTY IN MY MIND: THE ENDLESS HALF-LIVES OF IDM

By Simon Reynolds

At the outset, it needs to be said that “Intelligent Dance Music” is—ironically—kind of a stupid name. By this point, possibly even the folks who coined the term back in 1993—members of an online mailing list mainly consisting of Aphex Twin obsessives—have misgivings about it.

For as a guiding concept, IDM raises way more issues than it settles. What exactly is“intelligence” as manifested in music? Is it an inherent property of certain genres, or more about a mode of listening to any and all music? After all, it’s possible to listen to and write about “stupid” forms of music with scintillating intellect. Equally, millions listen to “smart” sounds like jazz or classical in a mentally inert way, using it as a background ambience of sophistication or uplifting loftiness. Right from the start, IDM was freighted with some problematic assumptions. The equation of complexity with cleverness, for instance—what you might call the prog fallacy. And the notion that abandoning the functional, party-igniting aspect of dance somehow liberated the music and the listener: a privileging of head over body that reinforced biases ingrained from over 2,000 years of Western civilization, from Plato through St. Paul and Descartes to more recent cyber-utopians who dream of abandoning the “meat” and becoming pure spirit.

And yet, and yet... Dubious as the banner was (and is), under that aegis, some of the most fabulous electronic music of our era came into being. You could even dance to some of it! And while its peak has long since passed, IDM’s half-lives echo on around us still, often in the unlikeliest of places: avant-R&B tunes like Travis Scott’s “Goosebumps,” tracks like “Real Friends” on The Life of Pablo, even moments on “The Young Pope” soundtrack.

You could say that the prehistory of IDM was the ambient chill-out fad of the first years of the ’90s, along with certain ethereal and poignant tracks made by Detroit producers like Carl Craig. But really, it all kicks off in 1992 with Warp’s first Artificial Intelligence compilation and its attendant concept of “electronic listening music,” along with that same year’s Aphex Twin album Selected Ambient Works 85-92 (released on Apollo, the ambient imprint of R&S Records). Warp swiftly followed up the compilation with the Artificial Intelligence series of long-players by Black Dog Productions, Autechre, Richard D. James (operating under his Polygon Window alias, rather than as Aphex), and others. Smaller labels contributed to the nascent network, such as Rephlex (co-founded by James) and GPR (which released records by The Black Dog, Plaid, Beaumont Hannant). But it was Warp that ultimately opened up the space—as a niche market as much as a zone of sonic endeavor—for electronic music that retained the formal features of track-oriented, rave floor-targeted dance but oriented itself towards albums and home listening. ELM, as Warp dubbed it—IDM, as it came to be known—was private and introspective, rather than public and collective.

Phase 2 of IDM came when other artists and labels rushed in to supply the demand, the taste market, that Warp had stirred into existence. Among the key labels of this second phase were Skam, Schematic, Mille Plateaux, Morr, and Planet Mu. The latter was the brainchild of Mike Paradinas, aka μ-Ziq— one of the original Big Four IDM artists, alongside Aphex, Autechre, and Black Dog. (Or the Big Six, if you count Squarepusher and Luke Vibert, aka Wagon Christ/Plug). Most of these artists knew each other socially and sometimes collaborated. All were British.

The two stages of IDM correlate roughly with a shift in mood. First-phase intelligent tended to be strong on melody, atmosphere, and emotion; the beats, while modeled on house and techno, lacked the “oomph” required by DJs, the physical force that would cause a raver to enthuse about a tune as bangin’ or slammin’. Largely in response to the emergence of jungle, with its complex but physically coercive rhythmic innovations, Phase 2 IDM tended to be far more imposing and inventive with its drums; at the same time, the mood switched from misty-eyed reverie towards antic excess or whimsy. Often approaching a caricature of jungle, IDM tunes were still unlikely to get dropped in a main-room DJ’s set. But by now, the genre had spawned its own circuit of “eclectronica” clubs on both sides of the Atlantic, while the biggest artists could tour as concert acts.

You could talk about a Phase 3 stage of IDM, when the music—not content with borrowing rhythmic tricks from post-rave styles like jungle—actually moved to assimilate the rudeboy spirit of rave itself: the original Stupid Dance Music whose cheesy ‘n’ mental fervor was the very thing that IDM defined itself again. This early 2000s phase resulted in styles like breakcore and glitchcore; these had an international following and, for the first time in IDM’s history, a strong creative basis in the United States. Drawing on an array of street musics from gangsta to gabba, upstart mischief-makers like Kid606 and Lesser made fun of first-wave IDM’s chronic Anglophilia, releasing tracks with titles like “Luke Vibert Can Kiss My Indie-Punk Whiteboy Ass” and “Markus Popp Can Kiss My Redneck Ass.” Around this time, IDM pulled off its peak achievement of mainstream penetration when Radiohead released Kid A—an album for which Thom Yorke prepared by buying the entire Warp back catalog.

Seventeen years after that (albeit indirect) crossover triumph, the original IDM crew continues to release sporadically inspired work. Autechre’s discography is quite the feat of immaculate sustain, Richard D. James unexpectedly returned to delightful relevance after a long silence, Boards of Canada remain a treasure. Label-wise, there’s Planet Mu, who appear to be unstoppable, hurling out releases in a dozen different micro-styles. Overall, though, you’d have to say that IDM as a scene and a sound doesn’t really exist anymore. But its spectral traces can be tracked all across contemporary music, from genius producers like Actress and Oneohtrix Point Never, to the abstruse end of post-dubstep, to Arca’s smeared, gender-fluid texturology. Its reach goes way further: I’m constantly hearing IDM-like sounds on Power FM, the big commercial rap/R&B station here in L.A. At the end of the day, stupid name though it may be, IDM has given the world a stupefying immensity of fantastic music. And its reverberations have yet to dim.

Simon Reynolds is the author of the techno-rave historyEnergy Flashand, most recently, the glam chronicleShock and Awe.

Jason Forrest

The Unrelenting Songs of the 1979 Post Disco Crash

Sonig

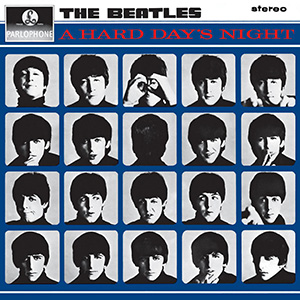

It’s unusual to find glam-rock in the genealogy of an IDM album but, with The Unrelenting Songs of the 1979 Post Disco Crash, breakcore artist and disco DJ Jason Forrest exuberantly weaves together samples from the likes of Elton John and Starship. It’s sort of a loving tribute but, while the odd bombastic drum solo or Beatles sample is left whole enough to be recognizable, these snippets of sonic excess combine into something singular and otherworldly. The sounds themselves are familiar, but they’re arranged in wild forms, the compositions often twisting in directions that are disconcertingly abstract.

Tracks like “180 Mar Ton,” with its frenetic chopped-up guitars and shout-along interludes, summon an infectious kind of hyperactivity, which can just as quickly give way to the noisy disintegration of “Big Outrageous Sound Club” or the blown-out psychedelia of “An Event (helicopter_passing—(edit)—251001.mp3).” Elegant it’s not, but Unrelenting makes for an energizing listen. –Thea Ballard

Listen:Jason Forrest: “180 Mar Ton”

Kid606

Down With the Scene

Ipecac

Whether it was his young energy (he was 21 when Down With the Scene was released), his San Diego upbringing, or, more likely, all of that combined with his own omnivorous curiosity, Kid606 helped upend IDM’s stereotype of bloodless astringency. Everything from noise-rock blasts to hip-hop’s world-conquering bravado to jungle’s hyperspeed breakbeats fed into his chaotic, fragmentary, and compelling collages—works of experimentalism utterly unafraid to laugh at themselves and the world.

Down With the Scene is a kaleidoscopic effort and a half. There’s smooth swagger on “GQ on the EQ” and gentle sweetness with “For When Yr Just Happy To Be Alive” slamming up against frenetic compositions like “Punkshit” and “Two Fingers in the Air Anarchy Style.” As for the scene in question, titling the second song “Luke Vibert Can Kiss My Indie-Punk Whiteboy Ass” and throwing in samples from CB4, among other sources, creates its own perverse salute. –Ned Raggett

Blectum from Blechdom

Haus de Snaus

Tigerbeat6

Blectum from Blechdom’s impulsive, glitchy electronic music is simultaneously challenging and unpretentious—fun, even. Kristin Erickson and Bevin Kelley, aka Kevin Blechdom and Bevin Blectum, met at Mills College in the late 1990s, and Haus de Snaus collects two of the women’s first releases, 1999’s Snauses and Mallards and 2000’s De Snaunted Haus. It charts an evolving—or maybe unraveling—sound built from a healthy dose of unhinged theatrics and fairly rudimentary software. (In an interview with Tara Rodgers in the book Pink Noises, Kelley recalls using a free, early version of ProTools that limited the number of times you could “undo.”)

The album’s first half is more reserved, establishing a tinny, raw sonic aesthetic and loose improvisational leanings on tracks like “Shithole” and “Cosmic Carwash.” It’s on the Snaunted Haus section, however, that Blectum from Blechdom’s personality comes to the fore in a series of spoken-word skits shot through with impenetrable mythology (with the snauses and mallards as recurring characters). Campy horror-film narratives punctuate the squelching electronics in what feels like gleeful defiance of experimental music’s self-seriousness. “What use is music that revolves only around having ‘chops’ and being ‘good’? Why feel obliged to wrap your body around some anachronistic sound vehicle?” Kelley asks Rodgers in Pink Noises. There’s something both libidinal and liberating in Blectum from Blechdom’s approach. –Thea Ballard

Mira Calix

One on One

Warp

When Chantal Francesca Passamonte’s full-length debut landed, she was 30 years old. That’s creaky by dance standards, yet youthful for institutional art music—in other words, the juncture suited her perfectly. By then, the U.K.-based Passamonte, who was born in South Africa, had already been releasing tracks for almost half a decade under the name Mira Calix, but it wasn’t until One on One that she committed to IDM’s native format: a proper album, the listener’s domain and wallflower’s autonomous zone.

Calix was an employee of Warp, and so she knew IDM’s hallmarks well. But on One on One, shepushes at those tropes. There’s metric play aplenty—like the scattered, anxiously looping “Skin With Me”—but the rhythms of “Routine (the Dancing Bear)” are decidedly un-digital, coming from a children’s metal toy. In the boys’ club of IDM, Calix made her female presence clear on “Ithanga,” mining her voice for tonal resources. Here, you can also peer into her future ambitious sound art, thanks to the infusion of classical instrumentation amid “Sparrow”’s textural irritants. –Marc Weidenbaum

Listen:Mira Calix: “Skin With Me”

Isolée

Rest

Playhouse

There was a moment, around the turn of the millennium, when IDM-aligned figures like Matthew Herbert started to embrace the slinky sensuality of the house template while weaving in glitches and clicks from the Oval/Fennesz world. The term “microhouse” was yet to be coined in 2000, but this is the undefined zone into which Rest slipped to wow the cognoscenti.

As the name hints, Isolée is a one-man-band, Rajko Müller. A German who spent much of his childhood in a French school in Algeria, his music is suitably cosmopolitan and border-crossing, connecting house and techno with ’80s synthpop and discreet touches of hand-played world music, like the Afro-pop guitar figure that flutters intermittently through “Beau Mot Plage” like a darting-and-dipping hummingbird. Müller’s sound works through the coexistence and interlacing of opposites: spartan and luxuriant, angular and lithe, crispy-dry and wet-look sleek, mechanistic and organic. Sensuous, ear-caressing textures juxtapose with abrasive tones as unyielding and chafing as a pair of Perspex underpants.

“Text,” the absolute highlight, is mystifyingly only available on the original 2000 compact disc. It’s an Op Art catacomb, a network of twisting tunnels, abrupt fissures, and pitch-shifted slopes that’s deliriously disorienting but never loses its dance pulse. Other tracks offer an exquisite blend of delicacy and geometry, like origami made out of graph paper, or echo the Fourth World electro-exotica of Sylvian-Sakamoto and Thomas Leer. We Are Monster, Müller’s 2005 follow-up, was excellent but a little too busy, losing the balance between minimal and maximal. So the debut remains Isolée’s true claim to acclaim, laurels on which Müller could Rest forever. –Simon Reynolds

Listen:Isolée: “Beau Mot Plage”

M:I:5

Maßstab 1:5

Profan

It’s difficult to name an area of electronic music that Wolfgang Voigt hasn't touched, either via his many production aliases or his hugely influential labels, Profan and Kompakt. His M:I:5 project ran through the mid-’90s, concurrent with his more famous work as Studio 1 and before he began his seminal ambient work as GAS. Maßstab 1:5 collects some earlier EPs and augments them, landing on the edges of the IDM scene largely due to a squiggle factor and textural vagueness not commonly associated with Voigt.

This being Voigt, Maßstab 1:5 still makes many other records on this list sound like New Orleans jazz, so committed it is to small tonal shifts and pinprick percussion. Grainy samples are mangled into new and shifty forms, such that even a sound as short as a snare hit seems to morph three times before it passes. Voigt also subverts techno paradigms by keeping much of his percussion slyly off-grid. This material was a formative text for the minimal techno movement on the horizon, and one wonders if the record’s title—translated “Scale 1:5”—wasn't already prophesying dance music's shrinkage.–Andrew Gaerig

Listen:M:I:5: “Maßstab 1:5 2”

Arovane

Tides

City Centre Offices

Germany’s Uwe Zahn made a handful of IDM-leaning records as Arovane, but none were as satisfying or as perfectly formed as this 2000 album. Because of its gently ebbing synths and hip-hop undertones, detractors might argue that Tides owes an obvious debt to Boards of Canada’sMusic Has the Right to Children—but Zahn’s innovations are significant enough that they don’t quite resemble anything else.

Much of this stems from Zahn’s frequent use of the harpsichord, which gives the music an uncommon, baroque stateliness. Elsewhere, Christian Kleine’s bright and uncomplicated guitar lines move things further away from the early Warp axis of influence by evoking the languid post-rock of Chicago’s Thrill Jockey. Combined with Zahn’s knack for plaintive, keening melodies and Tides’ succinct run time, that inventiveness makes for a low-key gem that’s still as functional and as evocative today as it ever was. –Mark Pytlik

Listen:Arovane: “Theme”

Bola

Soup

Skam

Manchester’s Darrell Fitton has all his IDM bona fides: a track on Warp’s Artificial Intelligence Vol. 2 comp, an assistance credit on Autechre’s debut album, a hand in Gescom’s shadowy productions. But even without that history, his 1998 debut album as Bola puts him in the upper echelons of ’90s electronic music.

Soup hovers somewhere between his mates Autechre’s clanging, mechanized rhythms and the warm reveries conjured by Boards of Canada—which is only fitting, as Bola shared a label with those Scottish brothers. Still there’s something about Fitton’s handiwork here that strikes a different set of nerves: He never pretends to be post-human like the former, and he never sets about conjuring that lost sense of childhood innocence like the latter. Instead, Soup stakes out its own sonic space, at once poignant, bracing, and cinematic. –Andy Beta

Listen:Bola: “Forcasa 1”

The Black Dog

Spanners

Warp

The Black Dog emerged in early 1990s, during the heyday of Aphex Twin, µ-Ziq, and the like: a world ruled by grinning electronic pranksters, jokesters, and clowns. Spanners, the trio’s third album, is their cheekiest entry into the lexicon of dance music, and proposes a scenario for its listeners: What if you entered a club and it was just a never-ending hall of funhouse mirrors?

Throughout Spanners, sounds are in flux, stretching into strange and hilarious shapes without warning or reason. The 10-minute epic “Psil-cosyin” feels like dozens of micro-songs combined as whistling synths morph abruptly, like Flubber flying through through the air haphazardly. Yet amongst all their jokes, the group (which is comprised of Ken Downie, Ed Handley, and Andy Turner) also offers a studied survey of global vernaculars, retrofitting Latin rhythms, Middle Eastern scales, jungle, hip-hop beats, and more into their Rube Goldberg machine. Spanners was the last time they worked in this configuration, and their final brainstorm still teems with rollicking energy. –Kevin Lozano

Listen:The Black Dog: “Psil-cosyin”

Anthony Manning

Islets in Pink Polypropylene

Irdial

Before IDM became a nation of Aphex and Autechre cosplayers, the genre was less defined by aesthetics than by a shared ideology. Here was a loosely connected axis of post-rave kids, united by little more than a shared willingness to subvert the tools of their techno idols and create sounds that hadn't previously been imagined.

No record of the era better embodies this find-a-machine-and-freak-it ethos than Islets in Pink Polypropylene, the otherworldly debut by British producer Anthony Manning. Built entirely on a Roland R-8, a chunky digital drum machine then celebrated for its realism, Islets is a meticulously crafted, multitracked flurry of kicks and hi-hats pitch-shifted into unrecognizable bubbles and squelches. For Manning, it was as if rhythm and melody had never been distinct elements to begin with, and his fusion of the two set an early precedent for the digital signal processing abuse that would come to define IDM at the turn of the century. –Andrew Nosnitsky

Listen:Anthony Manning: “Untitled”

Caribou

Start Breaking My Heart

Domino

On his 2001 debut album, Ontario’s Dan Snaith imagined how IDM might sound if its usual iciness and austerity thawed, just a little. Although still a fundamentally cold-weather record, Start Breaking My Heart hums with traces of the same acoustic textures and percussive abandon that Snaith would later dial up on future Caribou outings—and they introduce some much-needed warmth into the genre.

That sense of humanity extends beyond the instrumentation. With personal references in the song titles (“Paul’s Birthday,” “James’ Second Haircut”) and cover art depicting Snaith’s hometown of Dundas, Ontario, the extra-musical aspects of Start Breaking My Heart stand in direct opposition to the computer-generated artwork and hexcode-inspired track names of IDM’s antecedents. To Snaith’s credit, these bright-eyed and confident songs largely resist the urge to wallow in nostalgia, evocative as they are. –Mark Pytlik

Listen:Caribou: “Paul’s Birthday”

Leila

Like Weather

Rephlex

IDM, for all its love of the obtuse, has produced a number of fabulously esoteric pop songs over the years, from Squarepusher’s “My Red Hot Car” to Aphex Twin’s “Come to Daddy.” Leila’s “Won’t You Be My Baby, Baby,” the penultimate track on Like Weather, is another fine example of this art, the suck of a backward sample rubbing up against sun-shrivelled horns and an admirably lusty soul vocal.

It is this modus operandi that typifies Like Weather, the debut album from the sometime-Björk collaborator Leila Arab. Over 13 tracks, she subjects pop music to the kind of open-minded mangling that sees the excellent “Knew” cut off mid-chorus, the vocal on “Don’t Fall Asleep” pitched and shifted to an eerie whisper, and “Underwaters (One for Keni)” submerged in aquatic filters. Leila’s singular vision makes Like Weather a tough record to classify, falling somewhere between the dusty soul of trip-hop, the sensual elegance of R&B, the sugar rush of pop, and the fiddly experimentalism of IDM. But for the gorgeous swirl of strings and electronics on “Space, Love,” the tortured amen breaks of “So Low… Amen,” the astral synths on “Melodicore,” and the hissing hi hats and curdled chords on “Away,” the album deserves a celebrated place in IDM’s ranks. –Ben Cardew

Pan Sonic

Vakio

Blast First

IDM often emphasizes complexity over simplicity: tangled textures, intricate details, and convoluted rhythms. Finland’s Pan Sonic (née Panasonic, before the Japanese electronics giant got wind of their name) took the opposite route on their debut album, 1995’s Vakio. They don’t merely eschew software and other digital tools; they even forgo traditional polyphonic synthesizers in favor of rudimentary oscillators, noise generators, and hand-soldered behemoths that crackle with electrical currents and seem to breathe pure fire. Techno’s steady, four-to-the-floor pulse serves as the music’s rhythmic baseline, but the nuanced textures of their syncopated bleeps and sandblasted noise bursts tilt them away from club contexts and toward headphone listening. That said, abandoned meat lockers or frozen Soviet nuclear bunkers might be the most appropriate places to experience their chilling electronic minimalism. –Philip Sherburne

Listen:Pan Sonic: “Virhe”

Jon Hopkins

Immunity

Domino

A key slots into a door somewhere in East London. Just as quickly, the door shuts, and all signs of human presence—the trickle of traffic in the background, foreboding footsteps—are sucked into a crisp whirlpool of synthesizer pulses. The interdimensional portal Jon Hopkins opens at the start of Immunity leads to a space that feels and sounds a lot like our world, but it’s darker, more private, and wildly mercurial. His palette of noises was distilled from common domestic objects—the vibration of a piano string, fingers drumming on the side of a desk, the shuffle of salt and pepper shakers. Hopkins applies these found sounds onto commanding analog synths, violent drums, and cold pianos, creating a soundscape both opulent and engulfing.

The arc of Immunity is supposed to resemble a night out, with moments of plaintive rest, anxious activity, and endorphin-fueled release. Hopkins’ hour of music creates a lifelike nocturnal diorama by merging pastoral ambient, backbreaking dance music, and even contemporary classical forms into a new electric world. –Kevin Lozano

Plaid

Not for Threes

Warp

IDM is rich with instrumental counterpoint, so it makes sense that many of its best practitioners come in pairs: two instrumental perspectives heard in tandem, and often at cross purposes. There’s Autechre’s Sean Booth and Rob Brown, Matmos’ Drew Daniel and MC Schmidt—and also Ed Handley and Andy Turner, who as Plaid made their Warp debut in 1997 with 16 tracks of perplexing beats and floral melodies. (The duo began as two-thirds of Black Dog, ceding the name to Ken Downie after becoming Plaid.)

What makes Not for Threes rewarding, even 20 years after its release, is the breadth of Plaid’s references. Sure there’s the Tron-like intro to “Seph” and the dubby techno of “OI,” plus plenty borrowed from hip-hop. But listen as the simulated chamber music of “Milh” gives way to hyper-detailed syncopations, and dig the jazz underpinnings of “Getting.” They can also be chipper: There’s no nihilism, or rose-colored nostalgia, in the delightfully upbeat “Fer.” And while female voices in IDM often surface from inside samplers, Plaid invited actual humans to sing—including Nicolette, on the sultry breakbeat of “Extork,” and Björk, whose “Lilith” set the stage for Vespertine four years later. –Marc Weidenbaum

Listen:Plaid: “Seph”

Jlin

Dark Energy

Planet Mu

The history of IDM is, in part, the transformation of functional dance styles into forms that are weirder and more personal, with some of their rhythmic utility abstracted in the process. Acid, electro, and drum’n’bass are the styles that fueled IDM’s ’90s heyday, but more recent forms like dubstep and footwork have also followed this path. Footwork—a mutation of ghetto house that was born weird and inscrutable, with arrhythmia—was a particularly likely candidate to be put through the IDM blender next.

So arrived Jlin in 2015, a Gary, Indiana, resident isolated from the churn of Chicago’s battles and parties. On Dark Energy, she took a spark she found in 2010—when her track “Erotic Heat” appeared on the seminal Bangs & Works Vol. 2—and let it smolder for a half decade. Here, footwork’s manic template remains, but Jlin has vacuumed out the style’s irreverent roughness and replaced it with something far denser and more severe. Dark Energy’s rhythms and architecture mean it’s still recognizable as footwork; it’s everything we don’t recognize that makes it IDM. –Andrew Gaerig

Listen:Jlin: “Guantanamo”

Pole

1

Kiff SM

As the story goes, Stefan Betke was working as a mastering engineer and DJ in mid-’90s Germany when he broke a Waldorf 4-pole filter module and liked the sounds that resulted. His 1998 full-length debut as Pole, simply titled 1, had a similar immediate appeal to IDM listeners worldwide. 1, and much of Pole’s initial work that followed, could almost be summed up as “dub meets glitch,” but that’s too reductive: From the opener, “Modul,” 1 feels like an accumulation of layers around careful, pinpoint precision and a dreamy, floating mix of elements that ebb and flow. Tics and crackles (courtesy of said damaged filter) often nervously sit up front in the mix—like a nagging insect, but with a quality that draws you in rather than prompts recoil—while bass tones, keyboard loops, and more emerge at points from swathes of reverb. If there’s an underrated quality to 1, it’s in the album’s sequencing: Consider how “Fragen” feels like a gentle acceleration and rise near 1’s start, or how a song like “Tanzen” in the middle keeps the energy pulsing perfectly. –Ned Raggett

Listen:Pole: “Fragen”

Burger/Ink

[Las Vegas]

Harvest

[Las Vegas] marks a moment for IDM in which ideas were coalescing and new conversations were arising. Some of its influence is circumstantial; few predicted the globally prominent rise of Cologne’s dance music and Kompakt Records soon after its release, or that Matador’s issuing of the album in the U.S. two years later would open its indie-rock listeners to electronic beats. Yet it’s also true that the music made by Jörg Burger and Wolfgang Voigt (aka Mike Ink), two of the city’s techno lynchpins, was gorgeous and unlike anything that preceded it.

Featuring track titles high on Roxy Music and Americana pop, the trio of prior EPs that were collected as [Las Vegas] offer relaxed, melodic ambiance and warm, dubwise thump. They’re stoned rather than ecstatic, adult without being stuffy. Almost accidentally, the package strikes an LP’s balance and flow. Some tracks seem composed for the home, like the gorgeous “[The] Jealous Guy (From Memphis),” with a downtempo drum-machine pace and emotionally overwrought keyboard lines. Other songs, like the endlessly reverberant and percussive “Twelve Miles High,” are readymade for sunrise trance states. Then there’s “Do the Strand,” which gathers ideas from multiple strains of then-current German dance music (Basic Channel’s dub, Roman Flügel’s minimal house, sometime-partner Jürgen Paape’s disco deconstruction) into a glorious blueprint for Kompakt, the label Voigt would help launch in ’98. –Piotr Orlov

SND

Atavism

Raster-Noton

When Mark Fell and Mat Steel released Atavism, it was their seventh album as SND, as well as their first in seven years. The hiatus wasn’t one of inactivity, though; their return—largely heralded by the triple-12” 4,5,6—was a blossoming of ideas. What once has been accomplished glitch electronica was now mesmeric, algorithmic shimmering punctuated with crisp percussion. A severe and reduced sound palette zeroed in on rhythms that were sometimes quite erratic, creating a transfixing listening experience.

SND were clearly influenced by house, techno, continental experimental electronics, and a lineage of British post-rave, including Autechre and Warp Records. (They’re from Sheffield, original home of Warp, and have toured with Autechre.) Still, Atavism creates a world that is starkly individual. It’s considered SND’s last album, although they’ve never formally disbanded or retired the group moniker, and Fell has gone on to mine this territory in gorgeous, forensic detail with his solo career. Their imprints are all over a new generation of artists—including Lorenzo Senni, Gábor Lázár, and Fell’s own son Rian Treanor—who have incorporated their reductionism and digital pointillism into their own work. –Lisa Blanning

Listen:SND: “2”

Mouse on Mars

Glam

Sonig

Glam is an odd record, even within the catalog of the German electronic experimentalists Mouse on Mars. Initially recorded and rejected as a soundtrack fora Tony Danza comedy of same name, it went largely overlooked upon its initial release in 1998, and was issued only on vinyl in America during the peak era of CD sales. It wasn’t until a 2003 reissue on CD (with three bonus tracks) that Glam finally began to get the broader recognition it deserves.

This loping, sedate record is drastically different from the band’s first records, four beat-driven exercises in wonky, pseudo-dance music; it also sounds less dated and more timeless than anything else they’ve done before or since. The stately, seven-minute opener “Port Dusk” provides a nice thesis for the album’s form and approach, forgoing the group’s usual bouncy, off-kilter rhythms in favor of slow, droning synths laid over over skittish electronic bubbles. “Tankpark” and “Litamin” sound like futuristic takes on Ennio Morricone, while “Tiplet Metal Plate,” “Glim,” and “Hetzchase Nailway” pack a noisier, industrial patina. Glam the film may not have done anything for Tony Danza's legacy, but Glam the album has certainly helped cement Mouse on Mars as one of the most significant acts in the history of IDM. –Benjamin Scheim

Listen:Mouse on Mars: “Litamin”

Seefeel

Succour

Warp

On Seefeel’s 1993 debut album, Quique, the British quartet navigated a course between shoegaze and ambient dub—but by 1995, the electronic undercurrents of their sound had carried them to a very different place. Maybe it was the influence of Aphex Twin, whose remixes had honed in on the clean-lined rhythmic skeleton lurking beneath the group’s atmospheric swirl: The rolling, distorted drums of Succour’s “Fracture” and “Vex” are straight out of his playbook, and the beatless, bookending tracks “Meol” and “Utreat” both evoke Selected Ambient Works Vol. II at its most ethereal.

While the album’s textures and titles are often reminiscent of Autechre’s Amber, which came out the year before on Warp, Seefeel never entirely cast off their post-rock roots; squint through the fog of songs like “Extract” and “Cut,” and you can just barely pick out the familiar silhouettes of guitar, bass, drums, and microphone against the murk. Still, there’s no mistaking the common cause they make with the era’s knob-twisters and brain-dancers. Despite the echoes of other touchstones of the time (“Gatha” sounds like Massive Attack being dragged deep into an underwater cavern), it’s a singular album that has no equivalent—a sound so elemental, it’s no wonder the Designers Republic chose the cover they did. –Philip Sherburne

Listen: Seefeel: “Utreat”

Carl Craig

More Songs About Food and Revolutionary Art

Planet E

It might feel counterintuitive to think of a forward-looking, nebulous genre like IDM as having “roots revival music,” but if anyone had the means to make it, it would be a disciple of the Belleville Three. Carl Craig picked up the torch from the Atkins/May/Saunderson founding school of techno and carried it into entirely new territory. A fan of avant-electronic composers like Morton Subotnick and Pauline Oliveros, Craig proves an artist capable of merging multiple subgenres within a single song.

More Songs About Food and Revolutionary Art is IDM’s reckoning with techno, and vice versa. On “Televised Green Smoke,” layers of melodic mutation twitch into a Manuel Göttsching-worthy epiphany. On the oscillator-addled “Red Lights,” downtempo foot-drag beats evoke Giorgio Moroder in film-score mode, then get him woozy on ether. The mid-album stretch of “Dreamland,” “Butterfly,” and “At Les” is as cosmic as classic 4/4 techno gets, and the acidic, tension-building braindance of closer “Food and Art (in the Spirit of Revolution)” is the manic punctuation at the end of a stirring manifesto. On a record that treats the phrase “Intelligent Dance Music” as both a hijacking and a redundancy, Craig reclaims its identity on Detroit’s terms. –Nate Patrin

Listen:Carl Craig: “Dreamland”

Jim O’Rourke

I'm Happy, and I'm Singing, and a 1, 2, 3, 4

Mego

With its screwed-on eyes, button mouth, and metallic thread of a mohawk, the cover star of Jim O’Rourke’s foreboding 2001 glitch excursion is a human simulacra, a choirboy faceplate chanting hymns for the future. The music inside I’m Happy and I’m Singing and a 1, 2, 3, 4 follows suit, with the restless avant journeyman tuning his laptop in search of soul. The three long instrumental pieces that make up the record, which was recorded in the lead-up to Y2K and released months after 9/11, sound like the inner workings of a particularly modern robot. Yes, there is computerized repetition, but there’s also dread and joy and aimlessness and confusion. The record isn’t a warning cry for the incoming robo-pocalypse as much as a view inside a metal mind. Turns out, it’s a tumultuous place, full of synthetic breakdowns and droning despondency—all that noble compliance can be wearying. This is an album that will make you look at your computer—or your air conditioner, or your fridge—in a new light, and maybe feel a little bit bad for it. –Ryan Dombal

µ-Ziq

Lunatic Harness

Planet Mu

Mike Paradinas’s Planet Mu label has discovered and nurtured so many vital artists and scenes over the past 20 years—including Hrvatski, early dubstep producers like Benga, and Chicago footwork at large—that it eclipses Paradinas’ own body of work as μ-Ziq. Hyperactive through much of the ’90s, μ-Ziq’s discography can vacillate wildly, but with Lunatic Harness (his fourth album in five years), μ-Ziq struck the perfect balance between manic drum programming and gorgeous songs.

Lunatic Harness gobbles up the beats of the day—jungle’s chaotic drums, hip-hop’s beatboxing brio, the cerebral spasms of “braindance”—and weds it to lullaby-like melodicism. It’s a mix that only Paradinas’s good friend Richard D. James had previously attained, though Lunatic Harness is arguably the stronger, more sustained album that Aphex Twin never bothered to make. –Andy Beta

Listen:μ-Ziq: “Hasty Boom Alert”

Polygon Window

Surfing on Sine Waves

Warp

It’s tough to discuss the music of Richard D. James without also mentioning the more puckish elements of his persona. The man best known as Aphex Twin wasn’t merely one of the great electronic musicians of his generation; he also owned tanks and spun sandpaper records and trolled journalists and purposely snuck his music to market under a bevy of bizarre aliases. But he adopted the Polygon Window alter ego for a more utilitarian reason: a contractual workaround that enabled a move from the Belgian techno imprint R&S to the more adventurous British label Warp.

Surfing on Sine Waves is an appropriately transitional record in James’ discography. He had already begun to zoom in on the peripheral genre elements that he would later explode—acid squelches, crunchy hardcore kicks, synth washes, echoed-out whispers—but he seemed uninterested in any intentional stylistic deconstructions, let alone grand pranks. He was just knocking out some intuitively warped and melodically rich ambient techno because that’s what he did best. These days, Surfing doesn’t get mentioned as often as the louder, more ambitious, “proper” Aphex records that would follow, but it’s easily as refined on a technical level—and maybe even more emotionally rewarding. There’s something to be said for catching a genius in that sweet moment when their skillset is close to fully formed, but their ego is still in its infancy. –Andrew Nosnitsky

Venetian Snares

Rossz Csillag Alatt Született

Planet µ

One of three full-length albums that Aaron Funk released in 2005, Rossz Csillag Alatt Születettremains the most powerful and neatly conceptualized work of his career. Conceived while a heartbroken Funk was on tour in Hungary and found himself ruminating on the lives of the pigeons that populated Budapest’s Royal Palace, it is suffused with a very European melancholy. The Winnipeg native scaffolds his hypercomplex drum programming around samples of some of the giants of European composition: Bartok, Stravinsky, Mahler.

This manner of sampling can often feel ephemeral, a way of attaching exotic flavor or false gravitas to a project, but Funk brings a very authentic heaviness of spirit. The title translates to “Born Under a Bad Star,” and Funk embellishes these borrowed string quartets and operatic arias with his own violin and trumpet playing. Two particularly mournful tracks, “Galamb Egyedül” and “Második Galamb,” pay tribute to Budapest’s avian population, while the astonishing “Öngyilkos Vasárnap” (“Gloomy Sunday") is a cover of a 1933 ballad by the Hungarian composer Rezső Seress, and samples a version sung by Billie Holiday. Seress wrote it for his former fiancée, who later killed herself; he, too, ended his life in 1968, and the song is is now nicknamed “The Hungarian Suicide Song.” It is honored properly here: In Funk’s hands, the song and his other breakcore moments are elevated to high art. –Louis Pattison

Squarepusher

Hard Normal Daddy

Warp

Squarepusher mastermind Tom Jenkinson established himself as a prankster early on, through adventurous stylistic experiments that veered between jazz-tinged opuses and collages inspired by musique concrète. The reputation was cemented by Hard Normal Daddy, an entry in the drill’n’bass subgenre that upped the percussive ante of earlier styles, with some sincerity, too.

In a recent interview, Jenkinson sounded pure enough in his love for vintage, funk-infused scores like Herbie Hancock’s Death Wish soundtrack—which Jenkinson saidserved as an inspiration for Hard Normal Daddy. His claim holds up under scrutiny: “Cooper’s World” imports a stark and suspenseful two-chord theme ripped from ’70s genre cinema, and supports the riff with jungle-style beats. Toward the end of the lengthy “Papalon,” Squarepusher’s way of drawing out sustained tones over chaotic, clattering rhythms has an audible relationship to Hancock’s “Suite Revenge.”

On other tracks, Squarepusher twists away from the ’70s influence, letting his chords become more severe in their production style. The result isn’t anything that winks at you. Instead, the album feels playful in an innocent manner that is similar to a famed, subsequent experiment by André 3000—an avowed Squarepusher fan. On The Love Below, the rapper-producer adapted John Coltrane’s interpretation of “My Favorite Things” by outfitting it with a drill’n’bass percussion track: a choice that reveals the wide reach of Daddy’s influence. –Seth Colter Walls

Listen:Squarepusher: “Papalon”

Farben

Textstar

Klang Elektronik

Four-to-the-floor rhythms and IDM tend to be mutually exclusive, but that’s not always the case. In 2002, the year after Jan Jelinek sampled his way through stacks of vintage vinyl to create Loop-Finding-Jazz-Records, he applied a similar aesthetic to the first album released under his Farben alias. “Farben” is German for “colors,” but here, in shadowy tracks sourced from scraps of soul and mottled with digital grit, it’s the textures you notice first: dusty, sticky, slick as graphite, lumpy as a frog’s back. House music’s steady pulse runs through nearly every track, but it’s what he does around that taut guy-wire that makes the music tick: Tiny fizzing and clicking sounds flex and sigh in loose, elliptical rhythms, and soft, squishy synth tones lend a sense of elasticity to the quartz timekeeping. The references in a number of track titles—“Live at the Sahara Tahoe, 1973,” “Farben Says: Love to Love You Baby”—only add to the music’s mystery. –Philip Sherburne

Two Lone Swordsmen

Stay Down

Matador / Warp

Two Lone Swordsmen’s Andrew Weatherall can be credited with bringing electronic music to the mainstream in the 1990s, first with his transformative production on Primal Scream’s classic Screamadelica (which, in hindsight, sounds as much like his music as it does that band’s) and then with his remix work for My Bloody Valentine, Björk, and New Order. But it’s Weatherall’s late-’90s output with Two Lone Swordsmen that most impacted IDM. While his previous efforts as the Sabres of Paradise drew largely from acid house and dub, Two Lone Swordsmen created fluid, genreless compositions that mixed synthesizers, live instruments, and samples in a way that teased the many directions that experimental electronic composition could take.

On Stay Down, the band’s apex, the music moves from the delicate, melodious, vibraphone-driven “Ivy and Lead,” to industrial spy music (“As Worldly Pleasures Wave Goodbye...”), to what might be considered more traditional IDM (“Alpha School,” “Mr. Paris’s Monsters”). Stay Down showcases a group exploding with ideas that feel only loosely grouped together by taste, sensibility, and Weatherall’s love of the deep low end. –Benjamin Scheim

22. Listen:Two Lone Swordsmen: “Ivy and Lead”

Various Artists

Clicks + Cuts

Mille Plateaux

If terms like “IDM” and “glitch” seemed to be shrugworthy jokes or overused PR buzzwords by the turn of the millennium, Mille Plateaux’s remarkable 2000 double-disc compilation Clicks + Cuts made a great case for such experimental electronic music’s necessity. Sascha Kösch’s liner notes frame the release as exploring a new kind of minimalism, and the theme as such is of deep focus, centered around rhythms that don’t pound so much as pulse, throb, and skip. It’s music for both computer speaker setups and portable listening; within that framework, there’s astonishing breadth, from hyperactive activity to cool contemplation. The roll call of artists, and the quality of their contributions, is a master class in getting the right people at the right moment in time: Pole, Vladislav Delay, Pan Sonic, Kid606, Alva Noto, Reinhard Voigt, Farben, Sutekh, and more. Other striking moments: Dettinger’s “Strange Fruit,” with its early Kompakt label aesthetic; Neina’s beautifully hazy “Clairvoyance”; and Thomas Meinecke’s Framus Waikiki’s nervous, jittery “Rechanneled from Stereo.” –Ned Raggett

Listen:Neina: “Clairvoyance”

Urban Tribe

The Collapse of Modern Culture

Mo' Wax

Nineteen years after its release, too few people know The Collapse of Modern Culture. Even when it was new, the debut album by Detroit’s Sherard Ingram (best known today as the electro-leaning DJ Stingray) and a handful of the Motor City’s finest—Anthony Shakir, Carl Craig, and Kenny Dixon Jr., aka Moodymann—was too unusual a proposition to find a wide audience. It seemed too slow to be techno, too broken to be hip-hop, too electronic and vocal-free for most to recognize it as soul music. And the majority of the long-defunct Mo Wax label’s catalog never made its way to streaming services, which means this sumptuous, prescient slab of beat music has been relegated to the rarities bins. The drum programming and sampled breaks bridge boom-bap, Detroit’s slow-paced “beatdown” style, and the snapping grooves of Warp artists like Boards of Canada and Autechre; the mood throughout is melancholy and elegiac, with lyrical synthesizers poking through rumbling percussion like green saplings pushing through the rubble of a dead city. –Philip Sherburne

Matmos

A Chance to Cut is a Chance to Cure

Matador