![Cover Story: Natural Selection: How a New Age Hustler Sold the Sound of the World]()

One night in 1969, an anxious New Yorker named Irv Teibel discovered the perfect ocean. He couldn’t see it, couldn’t smell it, couldn’t dip his toes in it. But he could hear it, and the sound was all he needed.

Like a lot of searches, Teibel’s had started accidentally, when, earlier that year, a friend asked him to help record waves for a film project out on Coney Island. It was winter, freezing. The men rushed toward the shore and back with the tide, Teibel with a microphone in his hand and a tape player on his back. Even in the off-season, he found the beach loud, sleazy, nothing like the postcards promised.

Later, looping the tape in the editing room to sync with the film’s images, he noticed something: Normally while working with loops, he’d have to turn the volume down to stop the sound from driving him crazy, but this one didn’t bother him at all. In fact, the longer the loop played, the more relaxed Teibel felt. It was like finding a funny little rock on the side of the road, he said, only to take it out of your pocket later and realize it’s a diamond.

Teibel took his microphone back to the ocean in March, but the ocean didn’t comply. He walked 100 feet in either direction of where he first stood. He drove to Sandy Hook in New Jersey and Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts, eventually making his way down the Atlantic coast to Virginia, recording dozens of tapes along the way but never matching the sound rattling around his head.

Still, he persevered—perseverance was his way. He once said he drove Cadillacs because the NYPD didn’t have trucks big enough to tow them. When they did, he bought a bus.

Eventually, a friend named Louis Gerstman suggested Teibel pay him a visit. Gerstman was a professor and neuropsychologist working at the frontiers of speech synthesis, or, how computers might be used to analyze and render speech. A few years earlier he and a group of colleagues had taught an IBM to sing the nursery rhyme “Daisy Bell,” which later inspired the HAL 9000 in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. By the time Teibel met him, Gerstman was helping rehabilitate people after strokes.

The men fed one of Teibel’s Coney Island loops into an IBM 360, a huge, imposing machine that had the aspect of an airplane cockpit grafted to a refrigerator. Gerstman began processing the sound the way he might a sentence, breaking it into increments small enough to replicate and recombine, adjusting equalization settings and compressing dynamic range to make smoother shapes, adding new, synthetic waves with a random noise generator that masked the splices in the original tape, creating something that sounded uniform and continuous but non-repeating—something, in other words, natural.

After two sleepless nights and several hamburgers in and around a Bell Labs facility in Murray Hill, New Jersey, Teibel and Gerstman had not only matched the sound in Teibel’s head, but improved it: the perfect ocean.

By the end of 1969, Teibel had pressed an album called Environments 1: Psychologically Ultimate Seashore, credited to a company he called Syntonic Research, Inc. The name conjured lab coats, clipboards, a world beyond the vagaries of human error—not art, but science.

The album’s cover, a dreamy image of the shifting intersection between ocean and shore, looks like a brochure for an antidepressant; the back is marked by a hash of vague technical language and listener responses, each one in a different font and color—a polyphony of satisfied customers who can’t wait to share their discovery with you. “Better than a tranquilizer!” says one. “Cured my insomnia!” says another. “The hippest record ever!”

The album sold briskly and was written about in all the papers. The San FranciscoChronicle noted that a local freeform radio station played Teibel’s ocean for two weeks straight during a strike. Listenership improved.

In the part of the loop where the waves crested, Teibel had added a brief clip of his own voice making a vowel sound, played backwards. Among the hundreds of listeners who wrote letters to Syntonic over the next few decades, several singled the sound out, some concerned that they’d lost their minds, some accusing Teibel of planting subliminal messages. Teibel, a dry, confident man who liked disturbingly hot food, called it “my little joke.”

Now, Teibel’s concept—the soothing sounds of nature, or at least a synthesized facsimile of it—is quaint, the wallpaper of therapy waiting rooms and spa foyers. At the time, it was entirely new. Here was something you could hear but weren’t necessarily supposed to listen to. It wasn’t a sound effect, but it wasn’t music, either. And while it professed to contain the ocean, it had none of the purity or taxonomic specificity you’d expect from a field recording (never mind Teibel’s contention that the ocean could use a little work). Here was nature not as it is, but as we hope it’ll be, the lullaby of waves without the sand in our trunks.

The album’s novelty proved to be both an opportunity and a burden. Steve Gerstman, one of Syntonic’s first and shortest-lived employees, remembers traveling across the country by train, making his lonely pitch to stores. “The first obstacle is that it’s not music,” he said. “So if it’s not music, why would they carry it, and why would people buy it?”

Teibel’s answer? Stress. Troubled sleep. The existential plaque of modern life. You might shelve Environments with your records, but in conception it was more like a can opener or vacuum: Tools designed to streamline and optimize a task. Someone, somewhere, had tested it, and supposedly, it had worked.

Teibel was born in 1938 and raised in a narrow brick house in Buffalo, New York. (The house, which at the time of writing is in foreclosure, is listed as a “diamond in the rough.”) As a teenager he became fascinated with Gregorian chants, less for their spiritual valence than their efficacy as a homework aid. He studied at the Rochester Institute of Technology and the Art Center of Design in Pasadena, then moved to Stuttgart, Germany, for a job with the Army’s office of public information. “I am well and having a lot of fun doing battle with the Army,” reads a 1963 letter home, tone unclear.

A ravenous photographer with a natural curiosity about the intersection of art and technology, Teibel started experimenting with musique concrète, a term coined in the late 1940s by the composer Pierre Schaeffer for music made from pre-recorded—or physically “concrete”—sounds, as opposed to the abstractions of classical notation. Instead of playing instruments, Teibel learned to edit magnetic tape with razor blades; instead of performance, he learned the sensitivities of microphones and portable recorders—not music but sound.

Teibel enjoyed the process but tired of the product. “You come through with a technological masterpiece, but after listening to it for a half an hour there was a certain sigh of relief when the recording was over,” he remembered. “You didn’t have any inclination to go and repeat it.”

By 1964 he had moved to London, working as an art director for the ad agency Young & Rubicam and renting a flat from a lawyer in the Jewish neighborhood of Golders Green. “Reminds me (unfavorably) of the lawyer who used to live near the Pine Street Shul,” he wrote home. “Rather nosey and somewhat standoffish.” Then, wedged above the typewriting in pencil: “But his family is interesting.”

“Excuse me if I sound a little confused about my ultimate aims,” he continued. “My ultimate objective is to make a lot of money doing something I will be happy doing.”

Teibel made his way to New York, photographing for glossy magazines like Popular Photography and Car and Driver, falling in love with Sichuan and Korean food: pickled things, organ meats, the hotter the better. One friend remembers unknowingly eating a mouthful of chilies while Teibel tented his hands in Mephistophelean delight; another remembers Teibel declaring his love for udders, presumably because he knew it was an opinion in which he could be alone.

Teibel eventually landed an apartment on the 11th floor of an old research facility converted to artists’ housing at the edge of the city’s meatpacking district. The apartment overlooked the Hudson River, with a barber’s chair by the window and a telescope trained on the Statue of Liberty. Also in view was the West Side Highway, whose elevated second level was soon abandoned and repurposed as a de facto shade structure for junkies and cruisers passing through the shadows below. Almost everyone I talk to recalls a party Teibel threw during the 1976 Bicentennial, watching the tall ships sail downriver against time.

“A grand and glorious mess,” said one friend, a retired engineer named Arnold Goldberger, describing the place. “Filled with all kinds of things in vast quantities.” Books on gastronomy. Parking tickets. The occasional marijuana plant. Ray Erickson, a harpsichord player and professor with whom Teibel made a curious, one-off record in 1974, remembers coming to visit one afternoon and encountering a live bat in the hallway, swooping toward him out of the darkness.

The registry for the building listed Teibel as a filmmaker, a title that had more to do with his salesmanship than his artistic practice. As for friends: All of Teibel’s said he didn’t have many.

Syntonic took an office at the top of the Flatiron Building, a wedge-shaped skyscraper in lower Manhattan. Built in 1902, it remains one of the city’s most easily identifiable landmarks, the spatial remainder of a clash between the square intersection of Fifth Avenue and 23rd Street and the aberrant Broadway, which cuts diagonally across the grid at a 45-degree angle, making for a lot shaped like a slice of pie. This is the fever of urban life, architecturally expressed: Whatever isn’t used is wasted.

Miriam Berman, a graphic designer who worked with Teibel for years, remembers the surrounding neighborhood as quiet, almost pastoral. “We had a great view, with a balcony around the penthouse,” she said. “At that point, it was like living in the country.” Teibel, who seems to have been pathologically incapable of relaxing, felt otherwise. “Excuse me,” he said in the middle of a monologue recorded at his desk. “Every once in awhile it sounds like there’s a plane dive-bombing the Flatiron Building.”

In an effort to project an image of rigor and professionalism, Teibel staffed Syntonic with a handful of researchers, consultants, and customer-relations specialists over the years. Most of them turned out to be Teibel’s in-laws; just as many turned out to be Teibel himself. One call to a T-shirt manufacturer starts with Teibel introducing himself as Mike Kron from a non-existent company called SR Traders; on the next call, to another manufacturer, Teibel realizes he’s talking to the same guy he just got off the phone with—two lone hustlers hiding behind layers of corporate pseudonyms. Teibel laughs. The man laughs back.

Teibel ended up making 10 more records in the Environments series, each one a little more baroque in construction than the last. By “Wood-Masted Sailboat”(Environments 8), he was working with 24 separate tracks of sound, including seagulls from the Virginia shore, bell buoys from the Long Island Sound, a boom vang for the creaking mast, and an old chronometer from a clock shop on Lexington Avenue. In a gesture of decadence more in step with classic rock than sound therapy, he claimed to have once filled a soundstage with thousands of crickets because he could get a clearer recording indoors.

Teibel was working at a time when the country’s counterculture was merging tentatively with the mainstream. Vegetarian bibles like The Moosewood Cookbook entered the bestseller list; the last edition of the Whole Earth Catalog—a farmer’s almanac for the computer age that prefigured punk’s DIY ethic by about a decade—won a National Book Award. Yoga, previously an exotic dalliance for people with enough money to care, could now be found on morning television shows like “Lilias, Yoga and You.” Cooking, homebuilding, the general detoxification of self: Peace had become a personal concern.

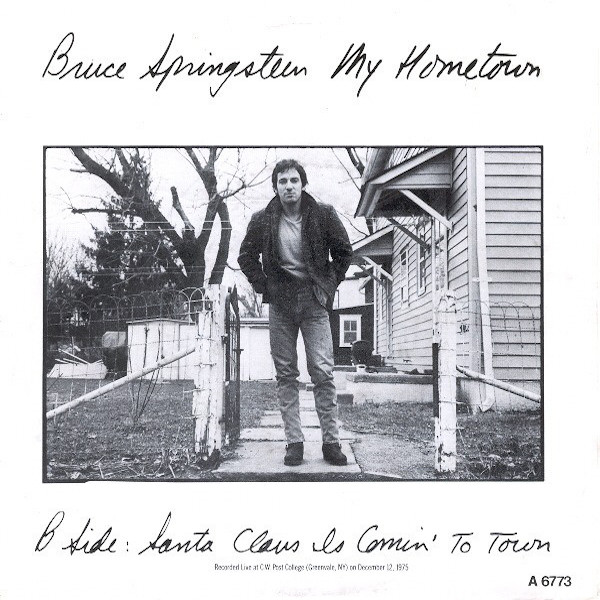

The first three albums in the Environments series were picked up for distribution by Atlantic Records, a label then busy taking over the world with Led Zeppelin and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. Nesuhi Ertegun,an Atlantic executive and one of the most artistically progressive and commercially intelligent figures in 20th century music, wrote Teibel a couple months after Christmas, 1972, to thank him for the umbrella. Business continued apace. The same time next year, Ertegun wrote to thank Teibel for the barometer.

Teibel was no environmentalist. If anything, nature was his obstacle, the raw material out of which he had to sculpt something more appealing. Reflecting on recordings made in Florida’s Okefenokee Swamp, one of the most unspoiled places in the country, Teibel said the bugs bothered him, the frequencies were hard to work with, and his terrier, Farfel, was harassed by alligators. As for the great symphony of night, Teibel slept with earplugs in.

Behind Environments’ hippyish premise—that we are biologically wired to thrive on the heartbeat of the earth—were coarser, more modern notions. By Teibel’s own admission, the series had been conceived not as a way to reconnect with the world but to shut it out. Everything about its packaging and presentation was haunted by the task of coping: of stabilizing in unstable situations, of squeaking through until the next day. The nature we hear in Environments isn’t only altered, but idealized, scrubbed free of machines, people and other hassles of civilization.

And yet Teibel sold these albums in part with the promise that they would help us sleep better and focus more. The moral is a capitalist one at heart: Our best selves and our best working selves are the same thing. That we have to twist mother nature’s arm in order to stay on top is collateral damage.

In 1970, about a year after Environments 1 came out, the biologist Roger Payne released an album called Songs of the Humpback Whale, which ended up going multi-platinum and fueled preservation efforts worldwide. (Payne’s work also ended up on Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan’s so-called “Golden Record,” which was shot into space with the Voyager craft in 1977—a distinction Teibel claimed for his ocean but which nobody at NASA would corroborate.) Teibel, a fast-talking cosmopolitan who probably could’ve sold water to a river in a rainstorm, didn’t seem half as concerned about what we could do for the whales as what the whales could do for us.

In some ways, Teibel’s project was an extension of exotica, a 1950s fad that blended Asian tonalities and Latin rhythms with ambient natural sounds, designed to transform the wood-paneled living rooms of postwar suburbia into the jungles to which its listeners would probably never go. One promotional snippet for Environments tells of a Miami resident who kept the windows of his beachfront apartment shut and Teibel’s ocean on the stereo because the humidity from the real ocean made his wall-to-wall carpet damp.

Like exotica, Environments was closely tied to the development of recording and home stereo technology, particularly the idea that a stereo’s quality is measurable by its ability to fool you into thinking the music is actually in the room with you—to conjure something “real.” Teibel himself was borderline obsessed with the issue, writing about speaker setup and listening conditions with the specificity and concern of a doctor outlining prescription dosages for a patient. If misused, the logic ran, the album’s intended effect was lost.

On learning that Environments albums were being broadcast at certain self-help seminars by holding a microphone to a speaker and feeding its signal through the building’s PA system, Teibel sent a sternly worded letter in all caps, assessing the practice as “QUITE FRANKLY… THE ABSOLUTE WORST WAY TO UTILIZE OUR RECORDINGS.”

The lecture continues for the remainder of the page, concluding by adding that of course Syntonic restricts all commercial use of their recordings, lovingly, Mike Kron.

Environments also marked an early expression of what we now call ambient music. Though synonymous with the 1970s, the roots of the concept could be traced back to 1950s composers like John Cage, who eschewed the scripting of specific sounds in favor of creating conditions in which sound—chancy, spontaneous sound—could occur.

In taking stock not just of the spotlight but the periphery, Cage argued, the audience could step into a state of meditative inattention, porous and dreamlike, wherein art was defined less by what it is than by the attention we pay to it. Suddenly even the clang of the elevator shaft sparkled with aura, the specific identity of something that happened without intention or event but would never happen again.

Still, even this was the echo of an older idea, advanced by the French composer Erik Satie. A pianist working in Parisian cafes during the 1910s and ’20s, Satie noticed that people almost never listened to music in the sanctity its composers had intended. They were drinking, they were talking, they were occupied by the stream of externalities we call life. Music, like good lighting or a decent chair, was less the object of experience than an accompaniment to it. Twenty years before the advent of elevator music and 60 years before the Walkman turned people into their own private theaters, Satie envisioned a world of continuous sound, inescapable and yet ignorable—as transient as the breeze.

One of his earliest experiments involved a group of musicians scattered around a gallery, playing incidental sound between theater pieces. Every time the musicians started, the audience would return to their seats. Satie scrambled around the gallery like a party host frantically micromanaging his guests. “Talk!” he yelled. “Move around.” In other words, don’t listen to the sound—be with it. “Furniture music,” he called it. If Cage argued that our surroundings could be music, Satie argued for music that disappeared seamlessly into our surroundings.

The question of science dogged Teibel for years. Despite broad and varied claims about the psychological benefits of Environments, Teibel never produced the kind of independent research that would’ve allowed him to be taken seriously in an academic forum. A firmly written letter from an editor at PsychologyToday, dated October 1976, bristles at Teibel’s insistence that Environments is of any concrete or measurable value, concluding that stories are nice but evidence is preferable.

In the absence of peer review, there’s always the theater of public opinion. As the series took off, Environments came packaged with customer feedback surveys, inquiring into everything from demographics and occupation to the make of one’s stereo system and speaker placement in their house. People responded at length, often appending typewritten commentary to the forms, digressing into their lives, their worries, their ailments and their solace—a patchwork of anxious, disconnected souls strung together with form stationery.

A blind man in Chicago wrote to say he played Teibel’s “Alpine Blizzard” at Christmastime. A lonely housewife in Soddy-Daisy, Tennessee, would retreat into Environments when her son and husband abandoned her for TV. A migraine sufferer says his doctor introduced him to Environments to miraculous effect, though he, like Teibel’s terrier Farfel, found the alligators of the Okefenokee Swamp unnerving. A Dairy Queen employee in Laurel, Delaware liked getting stoned and listening to “Night in the Forest” but wished the crickets weren’t so loud, while ABC News anchorHugh Downs worried the recordings were making him too sane, “rendering me unfit for my profession.” One fan professedly into “alternate life styles” suggests that Teibel receive a Nobel Prize.

My favorite piece of correspondence, from a Phoenix resident named Sherry January, approaches the naïve rhapsody of Gertrude Stein: “last nite I was reading the album cover & fell asleep I dream of the water the tree, the sunsat, the wind, and sky, that was on the cover in all its colors it all came to life, I was so chill from the wind and water, I woke up, I say what a dream.” Like a lot of new age tonics, Environments seemed to work in part because its consumers so deeply needed it to.

Environments kept Teibel relatively busy, but he still made time for extracurriculars. In 1973, he released a recording of President Nixon’s speech about Watergate, edited and rearranged to make it sound like an admission of guilt. The gesture wasn’t meant as protest so much as a demonstration of how illusory recordings can be. Or, in Teibel’s huckster aria, “a tour-de-force of sophisticated editing techniques which will undoubtedly send a chill up your spine.” Customers included Ted Kennedy and the National Intelligence Agency, a forerunner to the modern CIA.

In the wake of the Nixon recording, Teibel’s services were retained by Alan Berry, who, in the course of roaming the Sierra Nevada, claimed to have captured the sound of Bigfoot. The men exchanged no small volume of mail, but Teibel couldn’t offer much in the way of encouragement.

At one point, Syntonic even tried to break into book publishing with an offshoot called Simulacrum Press. Their sole publication was a reprint of a 19th-century book of arcana called The Complete Compendium of Universal Knowledge, which lingers over such subjects as how to occupy one’s self on a farm during every month of the year and how long it takes to digest an apple in microscopic font for about 500 pages.

I ordered a used copy from Amazon for a few dollars. Written in Sharpie on the inside cover was an inscription: “To Carol and Charlie, with gratitude, Irv Teibel.”

The spine remained unbroken.

Teibel hadn’t meant for Environments to preserve nature and yet, in its strange way, it did. Coney Island, where Teibel made his first ocean recording, was ripped up by Hurricane Sandy. The Bronx Zoo aviary, where he recorded “Optimum Aviary” for Environments 1, collapsed during a snowstorm in 1995. The Manhattan apartment where he recorded “Ultimate Thunderstorm” is still there, but the view is different, the dead zone between the West Side Highway and the river’s desiccated piers converted into a long, pastoral green belt where people jog and walk dogs.

Teibel’s old apartment building, Westbeth, is still there too, complemented by a pair of multimillion-dollar glass towers around the corner on Perry Street, designed a few decades later by Westbeth’s renovation architect, Richard Meier, in a neighborhood Teibel would not recognize.

I spent a large part of my childhood in a building across the street from Westbeth, watching the high heels of drag queens stride fabulously past the egress window on their way to the river during Pride Week, hitting tennis balls against the courtyard walls, growing up in a New York that, like all New Yorks, faded inevitably into the future.

Now when I hear Teibel’s thunderstorm, I picture him overlooking the upper level of the West Side Highway, taking in a view that no longer exists. Several years after making a serene, bucolic recording he called “Dusk & Dawn at New Hope, PA” Teibel went back to the site only to find an apartment building. “There weren’t any sounds around there,” he said. “Literally, those sounds had disappeared forever.”

Teibel died in 2010, after a long struggle with diabetes punctuated by cancer that killed him within weeks. I’m listening to his disembodied voice on a series of old tapes exhumed from storage by one of his daughters, Jennifer, who remembers him as a kind man, a funny man, restlessly creative, never without a camera dangling from his neck—an adult who still had it in him to sit down in the middle of a toy store and play.

Like Teibel, I’m faced with the job of creating the illusion of continuity from scattered tape. Unlike him, I give up: As much as I admire his perfect ocean, I prefer the vision of Teibel standing on the shore and waiting for planes from JFK to pass, cursing the ice cream truck as it stalks the boardwalk, its incessant jingle weaving through the beachgoers and the sunbathers and all the people capable of enjoying Coney Island for the noisy, saturated place it is, not for what it might be without us.

Within his archives is a simple, three-paneled comic of Teibel trying to record a single snowflake on its journey to the ground. In the first panel you can see him holding his microphone to the sky, uncertain if the signal is coming through. In the second, he’s smiling, following the flake at eye level, a child lost to the world outside his headphones. In the last panel we see a flurry of snow gathering over Teibel’s head, but he doesn’t seem to notice: He’s too focused on his single flake—a portrait of obsession and naiveté, of wonder we can’t cultivate but instead are born to lose.

The image was made by Miriam Berman, Syntonic’s graphic designer. The two had been a couple, which nearly everyone I talked to besides Miriam Berman chose to bring up. Her tone is weathered, bittersweet, edged by the laughter of someone practiced in keeping the past where it belongs. She accompanied Teibel on a lot of his little field trips, she said. He was fussy, obsessive, maybe a little brilliant, never quite satisfied. I asked in particular about one recording of a heartbeat, the only instance in the Environments catalog where Teibel acknowledges the presence of human life. “That was my heartbeat,” she said.

Teibel ended up marrying a woman named Rosanne in 1980. The ceremony was at Windows on the World, at the top of the North Tower of the World Trade Center. A small group of musicians played medieval repertoire in period dress. It was Sunday. The couple soon packed up and moved to Austin, Texas, where Teibel became a father twice over, got involved with the local Jewish community, and never made another recording for commercial use again.

Not that he gave up on Environments. The series was pressed onto cassette, and later onto CD, but Teibel’s primacy in the marketplace had been diluted. There was Songs of the Humpback Whale. There was a series called Solitudes. There were any number of budget-priced new age tapes of flutes or balalaikas or Celtic harps accompanied by the sound of rain and thunder that my mother bought at Pymander Book Shop in Westport, Connecticut, as part of her guided meditation to help try and assuage my childhood fear of death, and there’s the HoMedics SoundSpa sleep machine that my son drifts off to every night, programmable to replicate the ocean, the campfire, rain, and the Everglades—all ways we shut the world out in name of bringing it a little closer.

Teibel’s last employee was a hapless young musician named Bill Averbach. They met in synagogue sometime in the mid ’80s. By his own admission, Averbach couldn’t sell anything, let alone something nobody seemed to want, but he gave it a shot. He said Teibel didn’t reflect much on his legacy. Then again, it was such a short appointment, and so long ago, and Teibel wasn’t doing so well health-wise. Averbach’s clearest memories are of riding through the hills of west Austin in his boss’ Cadillac, Teibel smiling, leaning into every curve.

“You take a tenth of a second of an idea and suddenly it’s 10 years later,” Teibel said on one of his tapes. He pauses, then laughs. Then suddenly it’s 30 years later, and you have diabetes, then cancer, and you’re so mistrustful of doctors that your friends say you tried to treat yourself with diets, plums, fruits, healthy things, and none of it works, but at least you spent the time with your family, your camera, your daughters, taking pictures, documenting your secret, favorite subject: people.

More recently, the Chicago label Numero Group has been working on retrofitting Environments for a contemporary context. When Teibel first started out, he was limited by the half-hour side of a vinyl record. In several cases, he calibrated the sounds to make sense at various speeds, meaning that a listener for whom 30 minutes of the ocean was not enough could slow the album down and cruise for an hour. Then there was mobility. In dreams, Teibel envisioned a continuous, portable experience, something that could be adjusted to fit the rhythm and space of our lives rather than the other way around. He was a beat or two too soon. His daughter Jennifer tells me he had a smartphone toward the end of his life, and that he liked it.

Aaliyah performs in 1998; Photo by Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

Aaliyah performs in 1998; Photo by Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images