Longform: How Prince’s Androgynous Genius Changed the Way We Think About Music and Gender

Photo Gallery: Coachella 2016: Pitchfork Radio in Palm Springs

Greil Marcus' Real Life Rock Top 10: Further Reports on the Trump Soundtrack

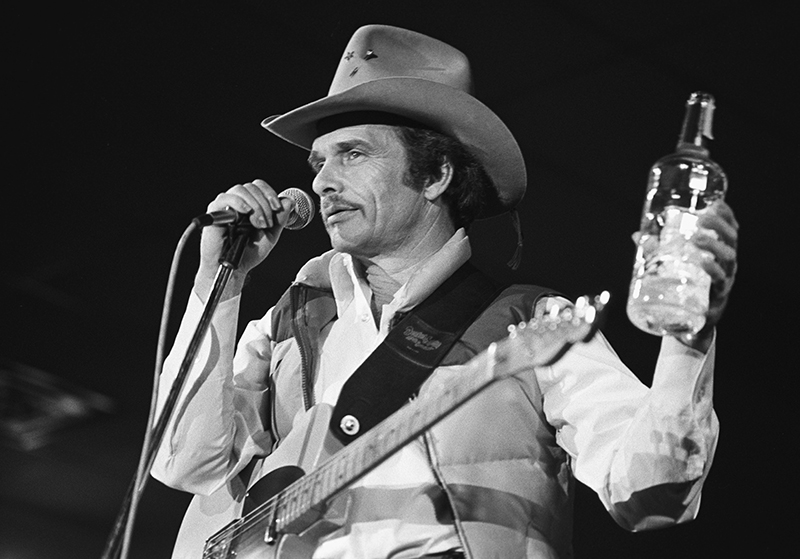

1. My friend Jo Anne Fordham writes in from Jackson, Mississippi, on April 6:“At 15, I saw Mick Jagger at Altamont. I was leaving as city kids lit evening fires in dry grass almost always visited by high winds. As soon as I saw Jagger's face, I knew I was far tougher. Not so, Merle. Never. RIP.”

2. Ensemble Mik Nawooj, The Future of Hip Hop (miknawooj.com) This Bay Area orchestra—guided by pianist JooWan Kim, with MCs Do D.A.T and Sandman, operatic soprano Anne Hepburn Smith, cellist Lewis Patzner, violinist Mia Bella D’Augelli, flautist Bethanne Walker, clarinetist James Pytko, stand-up electric bassist Eugene Theriault, and drummer Lyman Alexander II, with Christopher Nicholas on choruses—play with an elegant severity, which can break up into a back and forth between Do D.A.T. and Sandman that makes you forget the band until they throw the music back to the players like a second baseman completing a double play to first. Behind a music stand, Smith opens her mouth and as high, clear, swirling sounds come out, she makes you realize how much room there is in hip-hop—sonic room, conceptual room—that it’s a language that after more than 40 years remains in flux. The textures swimming through the sound are like the world’s fastest ping-pong game: they can make you dizzy, trying to hear and see everything at once, and you do. They make the Kronos Quartet, perhaps as much a model as Prince’s “When Doves Cry” band or the Roots, feel like they’re afraid of their own voice. No one seems capable of hitting a predictable note.

Ensemble Mik Nawooj: "Last Donut" (via SoundCloud)

3. PJ Harvey, The Hope Six Demolition Project (Island) This album may be about the collapse of the world, soulless capitalism, imperialism, and speaking truth to power—songs, or maybe more fully song titles, include “The Ministry of Social Affairs,” “River Anacostia,” and “Near the Memorials to Vietnam and Lincoln”—but clunky choruses and sing-songy rhythms make it plain that good intentions are not music. An attempt to ground ethereal singing—it all but screams not merely good but pure intentions—in a darker, slowly chanted “Wade in the Water” feels cheap. This album says everything it means to say in the profoundly discordant saxophone Harvey plays in “Ministry of Defence”—the sound she makes, huge plates of metal bending and scraping against each other, doesn’t last long, but the break it makes in the music echoes through the songs that follow, most often an echo of where they fall short. And when you go back to it, to try to feel how the sound was made, how it works, you can feel it: the collapse of the world.

4. William Bell, This Is Where I Live (Stax) Starting with “You Don’t Miss Your Water” in 1961, Bell had many hits on the R&B charts with Stax into the ’70s. This feels like the album he should have made in 1967, but wasn’t ready for: with every smoothly delivered lesson about satisfaction and pain, you sense how hard each one was to learn, and how finding the right words—the right tone of voice to make what you have to say mean anything—is much harder. With the most delicate, modest, contemplative soul guitar: in 1967 it would have been Curtis Mayfield, but it’s producer John Leventhal, who does the same for Rosanne Cash. Can’t Leventhal have Cash and Bell make their next album together?

5. The Rolling Stones, “Midnight Rambler,” from Sticky Fingers expanded edition (Rolling Stones, 1971/2015) A 1971 performance at the Roundhouse in London. On most of the American tour during the fall of 1969, and on Let It Bleed, released just one day before the Altamont finale, the song couldn’t take its shape. As the band played it they hollowed it out. It was there in full on Get Yer Ya-Yas Out! recorded at the end of the tour in New York—but not compared to this, two years later, where near the end Mick Taylor and Keith Richards find a rhythm in the song they’ve never heard before and begin to drive the music for its own sake, taking it right over a cliff. It’s what Richards described as the height of music-making in his Life: “if you're working with the right chord, you can hear this other chord going on behind it, which actually you're not playing. It's there. It defies logic.”

6. & 7. The Rolling Stones, “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” (1969) and Paul Krugman, “Learning from Obama,” The New York Times (April 1) Or, updating the Trump rally staple and why President Obama’s approval ratings have shot up over the spring: “Voters have lately been given a taste of what really bad leaders look like,” Krugman wrote. “I’d like to think that the public is starting to realize how successful the Obama administration has been in addressing America’s problems… Those caught up in the enthusiasms of 2008 feel let down by the prosaic reality of governing in a deeply polarized political system”—even if 10 million jobs have been created, Obamacare is working at a higher level and at a lower cost than predicted by the Congressional Budget Office, significant financial reforms are in place, and major climate protections have been imposed through executive action. “Assuming Democrats hold the presidency, Mr. Obama will emerge as a hugely consequential president—more than Reagan,” Krugman finished up: “The lesson of the Obama years, in other words, is that success doesn’t have to be complete to be very real. You say you want a revolution? Well, you can’t always get what you want—but if you try sometime, you just might find, you get what you need.”

8. The Shangri-Las, “Leader of the Pack” (Red Bird, 1964) Another shot on the Trump rally soundtrack—against the objections of Shangri-Las lead singer Mary Weiss. But really, Trump ought to know the song. He was 18 in New York when the New York group hit the top of the charts. Doesn’t he realize the leader of the pack dies?

9. Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductions, Barclays Center, Brooklyn (April 8) For the record: Ice Cube, the day before, in an interview in The New York Times with Joe Coscarelli. Coscarelli: “Gene Simmons, of Kiss, said a few years ago that rappers didn’t belong in the Hall of Fame, because they don’t play guitar or sing.” Ice Cube: “Rock’n’roll is not an instrument and it’s not singing. Rock’n’roll is a spirit. N.W.A is probably more rock’n’roll than a lot of the people that he thinks belong there over hip-hop. We had the same spirit as punk rock, the same as the blues.” Steve Miller, acceptance speech: “At the University of Wisconsin, I was a member of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. I was a Freedom Rider, and a war protestor.” “I encourage you,” he said at the end of his eloquent eight-minute address, “to keep expanding your vision. To be more inclusive of women. And to be more transparent in your dealing with the public. And to do much more to provide music in our schools.”

Women: the Shangri-Las have never been nominated, let alone inducted. But maybe that’s why Donald Trump doesn’t really know “Leader of the Pack”—they’re losers, and he doesn’t truck with scum.

10. Lonnie Mack, born July 18, 1941, Dearborn County, Indiana-April 21, 2016. Prince, born June 7, 1958, Minneapolis, Minnesota-April 21, 2016. Two guitarists from the Midwest. Who could toll their own bells.

Thanks to Daniel Wolff.

Longform: Blood and Echoes: The Story of Come Out, Steve Reich’s Civil Rights Era Masterpiece

From the Pitchfork Review: New York Is Killing Me: Albert Ayler’s Life and Death in the Jazz Capital

The following story is featured in the latest issue of our print quarterly, The Pitchfork Review. Subscribe to the magazine here.

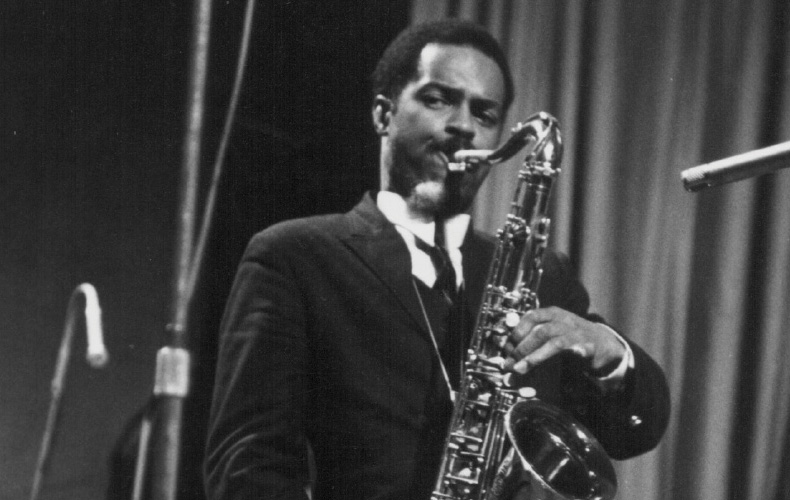

In the summer of 1963, a tenor saxophonist named Albert Ayler moved into a room in a flat owned by his aunt, across the street from St. Nicholas Park in Harlem. It wasn’t the 27-year-old’s first trip to New York City, but this time he’d come intending to stay. Ayler was heading into the New York jazz epicenter as a complete unknown. It was a tumultuous time for a music in the process of splintering into fragments, building on its storied past but unsure where it would go next. Giants of bebop like Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk were alive and well and cutting important records (the latter would in another year be on the cover of Time); Miles Davis was in a transitional period, but was on the verge of making some of his finest work, with his second great quintet right around the corner; Charles Mingus was humming at a creative peak, and Duke Ellington had been canonized but was still busy. If you wanted to be someone in jazz during this era, a time when the music still commanded attention, New York, then as now, was the place to be.

But for all the living history and the legends still making rent playing nightclubs and theaters around town, the real story in jazz in 1963 was the “new thing”—free jazz, introduced by Ornette Coleman in 1959 and codified in 1961 with his album bearing the name. By abandoning chords, the harmonic foundation of Western music, free jazz opened up new avenues for improvisation but also suggested the possibility of chaos. As the decade wore on, the sound and style of free jazz was closely identified with the black liberation movement, serving as both a metaphor—culture that breaks free of oppressive structure—and, through its sound, a direct expression of pain, anger, and redemption. The music developed alongside movements in other mediums. The cover of Coleman’s Free Jazz featured a detail from a painting by abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock; the splatter of paint, seemingly random but suggesting a deeper form, mirrored the approach of the musicians. It was the art of the accelerated moment, reflecting the hum and technological bent of the modern American city, and New York was its cradle. The jazz mainstream, however, was at this point still highly skeptical.

John Coltrane, who’d had a busy career as a sideman in the 1950s and had played with nearly everyone mentioned above at one time or another, was enamored with Coleman’s innovations, and was by 1963 busy shaping them to his own highly personal ends (in another 18 months he’d release A Love Supreme and would begin the fiery, intense march through music that consumed his last few years on Earth.) If the harmonically complex small-group form of bebop had transformed jazz from dance music to art music—sound designed to accompany careful listening instead of movement—free jazz forced listeners to reckon with fundamental questions about the nature of music itself. Naturally, many have no interest in this kind of introspection—they just want something that sounds good. So the life of a free jazz musician has often been a lonely and impoverished one. Albert Ayler, obsessed with the music of Coleman and Coltrane, had an idea that he could do something new with their innovations, a music as far out, and that exploded with energy, but that also had the grounded spirituality of the church.

That Ayler stayed with his aunt in New York was appropriate because family meant a great deal to him. His deeply religious parents, living in the middle-class neighborhood in the Cleveland suburb of Shaker Heights, were still very much part of his life, and he referred to himself as a mama’s boy, someone who “wore short pants” well into his teenage years. His younger brother, Donald, who shared Albert’s interest in music but hadn’t yet demonstrated the same level of skill, had always been a close companion.

Ayler had spent much of the last five years in Europe—first stationed in Orléans, France, during a three-year stint in the army, and then mostly in Copenhagen and Stockholm, where he bounced around, playing in different groups before a landing an on-and-off gig with avant-garde pianist Cecil Taylor that lasted several months. He’d recorded as a leader while in Europe, but few people had heard his records. His first album, cut in Sweden in 1962 and called Something Different!!!!!!, was released on a tiny label, and Ayler was reluctant to even record it in the first place. As he described it, the music he heard in his head hadn’t quite taken shape—he was imagining something beyond what he could reproduce, and he felt he was too early in his development to document his playing. But he did feel like he was on to something, that there was a sound beyond the limits of traditional jazz that he could explore, and he saw how his music could affect people. “When I was in Sweden, the people said, ‘Beautiful!’” he told an interviewer in 1970, speaking about the first time his unorthodox style of playing had been appreciated. “I said, ‘Oh, this is beautiful?’ They said, ‘If this is what you feel, it’s beautiful.’”

Ayler made friends easily. He was charming, soft-spoken, and thoughtful, with a slightly spacey presence, prone to connecting ideas about music to broader ideas about spirituality and the cosmos. The religion he grew up with never left him; in fact, it intensified as time wore on, taking on elements of the aquarian pantheistic New Age spirituality that was emerging in the ’60s. For Ayler, music was about tapping into universal vibrations that existed at a level outside of human consciousness, and he saw his art as a way to access something higher. He never fit the mold of the cool, laconic New York jazz musician; his style was more open and more excitable. As the decade wore on, Ayler’s far-out musings would intersect with the mainstream in unusual ways, even as his music always existed well outside of it.

At first, though, Ayler’s time in New York was all about the jazz scene, trying to fit in and make connections and be heard. The first semi-regular gig Ayler landed in the city was playing the Take 3 coffee house on Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village, working as a sideman with Cecil Taylor, with whom he had re-connected after their European stint. The Take 3, while never notable as a jazz venue, was part of a bustling scene in the neighborhood. Three years earlier, Nat Hentoff had written a piece for The New York Times outlining how the Village had become a hotbed for adventurous jazz. In years prior, the jazz scene had been centered further uptown, first in Harlem, and later along 52nd Street. The coffee house scene in the Village, which nurtured the rise of folk music and spoken-word performance, was receptive to the new music. In 1959, Ornette Coleman’s notorious New York debut had happened a few blocks away from the Take 3, at the Five Spot, where he had extended engagements in late 1959 and early 1960. Everyone had to see Coleman and weigh in on what he was doing; it was a place to be seen and was understood to be ground zero for a radical shift in music. Some of that furor had died down by 1963, but big changes were still ahead.

The shape Ayler’s music would eventually take was some distance from the dense, complicated, often atonal music favored by Taylor. Still, Ayler left an impression on those who heard him. Robert Levin, a jazz critic who wrote frequently for the Village Voice, first heard Ayler at the Take 3 in 1963 and described the sound as “astonishing,” the sort of sound that chased some people out of the room while those who remained were riveted.

Ayler was defined by that sound—when people heard him, they could tell he was something special after just a few notes. In high school back in Cleveland, he’d spent two summers touring with a band led by Little Walter, who had changed the sound of the harmonica in Chicago-style electric blues. Practicing relentlessly since he started playing as a boy, Ayler had developed a big, rich, honking tone, the kind of sound that could cut through a noisy bar and urge people onto the dance floor. Along with the sheer volume of his attack, Ayler gradually began to favor a sometimes absurdly wavering vibrato, which evoked the pathos of gospel music and brought to mind the mournful sound of an early 20th century New Orleans funeral processional. The final piece of his saxophone sound snapped into place when he found a way to integrate his booming tone and gospel-derived emoting in the context of free jazz, with its flowing and forgiving relationship to pitch and openness to screeching and bellowing at the horn’s extreme ranges. Ayler was finding that he could integrate all of these elements into new compositions he was writing, tunes that alternated catchy, sing-song melodies inspired by European folk songs and the propulsive marches he learned in the army band with highly textured and high-energy abstract playing almost completely divorced from form. It was an unusual mix of the cerebral and highly technical and the nakedly emotional.

The New York jazz scene had developed some ambient awareness of Ayler because of his stint with Taylor at the Take 3, but his breakthrough moment would happen uptown in Harlem, just a short walk from his aunt’s place. On Sunday afternoon, December 29, a copyright attorney named Bernard Stollman visited The Baby Grand Café, a club on 125th street that featured music and comedy, in order to hear Ayler, at the recommendation of a Cleveland musician he’d met. Ayler’s playing so impressed Stollman that he rushed to talk to him afterwards to say that he was starting a label and wanted Ayler to be his first artist.

Stollman signed Ayler with a $500 advance and Spiritual Unity, the album Ayler recorded for the new label, was recorded in July 1964. Though ESP-Disk was a tiny imprint with poor distribution, those aware of avant-garde jazz began to follow it closely, as Stollman documented an underground jazz scene that was growing in importance by the day. The group Ayler had assembled for Spiritual Unity, which included Sunny Murray on drums and bassist Gary Peacock, was turning quickly into a unit with an astonishing degree of empathy. Though Ayler was destined to dominate any setting he found himself in due to the sheer boisterousness of his tone and boldness of his ideas, he discovered in Murray and Peacock two expert listeners who truly understood what he was doing. Following the release of the record the group decamped to Europe, this time with momentum behind Ayler’s music.

Spiritual Unity is a classic album by any measure, but it misses something that Ayler would develop in 1965 and fully realize in 1966—how his deeply personal approach to melody and outsized expression could work in an ensemble setting. If Ayler’s bouncy march tunes were memorable when he was the sole melodic voice in a trio setting, they became overpoweringly infectious when played by a larger group.

Sensing the need for a new kind of ensemble while on tour in Europe, Albert wrote to his brother Donald in Cleveland. To that point, Donald had fiddled with alto sax and played gigs here and there in Ohio, but his playing was not particularly notable and he hadn’t developed a distinctive voice in the instrument. Albert told him to learn trumpet and move to New York when he was ready. He had two motivations. One, he and his brother were close, and Albert wanted family near him, and two, his vision for what his music could become was very specific, and required a horn in front who would play differently than anyone else on the scene at that time. Donald, who greatly admired his older brother and was excited by the idea of life as a jazz musician, could help to get him there, and he did as he was told, practicing his new horn every waking hour. Though his mother was devastated that her younger son was also leaving her and begged him not to, Donald prepared to move to New York with his brother.

By March 1965, both Ayler brothers were now living in New York. Albert had assembled a new band, one that hinted at everything his music would become during the next two years. Donald, though he had only been playing the instrument for a few months, was on trumpet. Lewis Worrell had replaced Gary Peacock on bass, and Sunny Murray was still playing drums. On March 28, for a gig at the Village Gate on Bleecker Street, just across the street and down the block from the Take 3, a cellist named Joel Freedman joined the band. It was an important evening for Albert. The new sound he was developing was coming close to reaching its final form, and the music was being recorded by Impulse!, the well-funded label whose marquee artist was John Coltrane. Coltrane was also on the bill on this night, along with astrally-focused bandleader Sun Ra, singer Betty Carter, and others. The evening was a benefit for The Black Arts Repertory Theater, founded by poet and jazz critic LeRoi Jones, later known as Amiri Baraka.

In his liner notes for the live album on Impulse! culled from this evening, The New Wave in Jazz, which featured the Ayler piece “Holy Ghost,” Jones wrote that “Albert Ayler is a master of staggering dimension, now, and it disturbs me to think that it might take a long time for a lot of people to find it out.” In Jones and Coltrane, Ayler was developing important admirers. During interviews in this period, when Coltrane was asked about new players on the scene, he almost always mentioned Ayler. Coltrane loved the younger man’s music, and in the past year, they had become close. Coltrane’s approach to music was one of deep focus and relentless study, and it’s possible that he heard in Ayler’s work a kind of playfulness and intuitive musicality that was harder for him to access. And for the rest of 1965, especially, Coltrane’s sound was deeply influenced by Ayler—it’s impossible to imagine pieces like the grandly anthemic “Selflessness” and the highly melodic themes of Meditations without Ayler’s presence.

Jones’ writing also served to place Ayler’s music, and free jazz in general, in the context of the tumultuous political changes, particularly those pertaining to civil rights. From its structure to its relationship to transition, free jazz was a natural soundtrack to the broader quest for freedom and equality, and Ayler’s music in particular, which was theoretically complex but also deeply grounded in the black music tradition, had a particularly intense relationship to the moment. Ayler himself described what he was doing as the blues, but a new blues, one that fit with what was going on in the world at this time. He was making music to praise God. He thought of it less as a call to arms and more as a soundtrack to the aftermath, a vision of what the world might become when peace and equality ruled the earth.

With Donald on board and the regular addition of strings, Albert’s music was reaching the peak of its power. Unlike the horn players Albert worked with previously, Donald was neither a subtle accompanist or breakout soloist on his own. His role now was something akin to a bugle player in a military band, bleating out the themes and helping to guide the band from one section to the next. When the themes would break down and people would start soloing, Donald was prone to a series of loud trills that generally had little in the way of variation. But his tone was rich and fat, reminiscent of trumpet players from before the bebop era, and he specialized in loud, deeply felt statements of melody that gave the tunes shape. And with strings in the band, Albert’s music was developing a symphonic grandeur to match the busy feel of the New Orleans-style ensemble, the classical instrumentation reaching back to the music’s European roots as the horns stayed rooted in African-American tradition. Another ESP album, Spirits Rejoice, recorded at Judson Hall on 57th Street in September ’65, finds a version of this band—joined by alto saxophonist Charles Tyler, a friend from Cleveland—in full flower.

Through 1965 and ’66, Ayler’s ensemble would gig often at Slug’s Saloon, a small club in the Lower East Side that was especially receptive to the daring jazz being created at the time. Opened in 1964, Slug’s was developing a reputation not unlike that of Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem two decades earlier—a place for the most adventurous musicians to gather and play for each other (in 1966 and ’67, Sun Ra had a regular residency at Slug’s). As heard on the double album At Slug’s Saloon, recorded in May ’66, Ayler’s shows had grown into long medleys where one song segued into the next, and the wild energy of his earlier solos were being channeled into unbearably intense statements of melody. The music was not “free” in the strict sense of the word, but it was open and welcoming and utterly unique, with a deep feeling of joy permeating the whole.

But if Ayler’s music was reaching new artistic heights, gigs at tiny clubs like Slug’s weren’t paying the bills. Ayler’s peak years as an artist in New York were also his most financially impoverished; he was releasing records on small labels like ESP and Debut and playing small rooms, and his band had up to a half-dozen members to pay. He was often desperate, to the point where he couldn’t afford to buy food, and to get by he frequently borrowed money, most often from his father or from John Coltrane. His mentor then did him one better. In the fall of 1966, at Coltrane’s urging, Impulse! offered Ayler a record contract; a gig recorded live at the Village Vanguard in December, with Coltrane in attendance, would form the basis for his first album on the label, Albert Ayler in Greenwich Village.

Trane was able to get Ayler signed to his label, and he was there in the room at the moment when the music from his first album for the imprint was created, but he wouldn’t live to see its release. In July of 1967, Coltrane succumbed to liver cancer at age 40, and one of this last requests was that his funeral would feature performances by Ayler, along with Ornette Coleman. The service, held at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church on Lexington Avenue, featured a performance by Ayler’s band—Albert and Donald, along with Richard Davis on bass and Milford Graves on drums—playing the balcony to open the event, and several minutes of the hair-raising performance survives on tape. Ayler played a medley of three of his best known themes—“Love Cry,” “Truth is Marching In,” and Donald’s composition “Our Prayer”—with an intensity and depth of feeling that almost defies belief; at the end of the segment, Ayler begins to solo on his horn and then he removes the saxophone from his mouth, screaming wildly and wordlessly in the church.

Following Coltrane’s death, Ayler’s life became a series of extremes. For a time, the Impulse! advance afforded him a certain degree of financial stability, but Ayler no longer had the great saxophonist in his corner. And Ayler’s music was on the verge of dramatic transformation, shifting to a more commercial rock and R&B sound. The reasons for this shift have never been clear. Some accounts have Impulse! executives encouraging Ayler to try his hand at more commercial genres in order to bring his music into the broader youth culture. His new girlfriend, Mary Parks, known professionally as Mary Maria, was also having a profound impact, encouraging his mystical pursuits and collaborating with him on new songs that included her lyrics. And Albert’s brother Donald, his increasingly erratic behavior fueled by heavy drinking, was inching toward what would later be described as a nervous breakdown, and was gone from the band by early 1968. That year saw the release of the album New Grass, followed by Music Is the Healing Force of the Universe. Though each has moments of adventurous experimentation remained (see the blistering bagpipe solo on “Masonic Inborn”), the albums were rife with now-dated flower-child lyrics by Parks and some shaky lead vocals form Albert. New Grass even opens with what amounts to an apology, a spoken-word section from Albert which he acknowledges that this music is different from what he’s played before, with a hope that listeners will give it a chance. Baraka’s magazine The Cricket responded with harsh reviews.

As the decade wound down, Albert was suffering from a tremendous amount of guilt about his brother’s unstable condition. His mother had not wanted Donald to move to New York, and now that he was unable to care for himself, she insisted that Albert step up. Albert and Mary wanted Donald to return to Cleveland, to be looked after at home. The rift in the family was causing an increasing amount of strain. For his part, Albert was trying for a quieter life. He moved out of Manhattan and into an apartment with Mary in Park Slope, Brooklyn. Sometimes the couple would play in the open air together in Prospect Park, he on tenor and Mary on soprano saxophone, which he was teaching her. Interviewed in Europe in 1970, Albert was asked about his place in the New York scene of the time. “It’s not for me,” he said. “I stay off to myself.”

The last months of Ayler’s life remain a mystery. The European shows were well received, and while the form of his music lacked the daring and intensity of several years earlier, recordings of two gigs find Ayler playing as well as ever. At some point during the year, Impulse! dropped him from the label. Despite his overtures to the mainstream, Ayler’s records sold badly. Some people describe Ayler behaving strangely later that year, including a report of him wearing a fur coat and gloves in the summer heat, his face covered in Vaseline. Others who saw him during these months noted nothing unusual. Mary Parks said that their precarious financial situation, coupled with concerns about Donald and the declining health of his mother, had pushed Albert into a dark place. Following an argument, he left their apartment and disappeared. She notified the police. Three weeks later, his body was found floating in the East River next to the Congress Street pier in Brooklyn, and the coroner said he’d drowned. Suicide seemed likely, but the circumstances of his death remain a mystery.

If Cleveland was Ayler’s roots and Europe was where he first saw a beautiful vision of what his music could be, New York is where all the threads of his music came together as one. In 1965, tenor saxophonist Archie Shepp, another Coltrane protégé (and a great admirer of Albert), called his new album Fire Music. Four years after Coleman’s Free Jazz, the title caught the feeling of the New York present, when the crackling energy of the music and the pulsing vibrations city met the righteous political fury of the moment. Ayler’s music captured the light and heat of this particular epoch perfectly, but the intensity proved to be too much. For him, life as a musician in New York was like pushing a boulder uphill. “I’m playing about the beauty that’s going to come after the tension and anxieties,” Albert said about his music in the liner notes to Live in Greenwich Village. He never got there, never got to see what the view of the sky looked like from the top.

Longform: Why the Death of Greatest Hits Albums and Reissues Is Worth Mourning

Longform: Grateful Dead Live On: Why the Legendary Band Still Matters

Yearbook: Chicago’s Disco Demoliton, Cheap Trick, and the Rise of House Music

In 1957 the great jazz bassist Wilbur Ware released an album called The Chicago Sound. That recording captured a fleeting moment in the city’s rich musical history, with an emphasis on the brawny and bluesy school of tenor saxophone style indigenous to Chicago, here due to the playing of Johnny Griffin. But applying its titular phrase in any broad sense to the city has always been foolhardy—if anything has ever defined the place, it’s been the variety of traditions thriving within and around its borders.

In 1979, Chicago’s music culture, disparate and expansive as ever, was undergoing a turbulent transition, even if didn’t seem that way at the time. Styx, Chicago, REO Speedwagon, Head East, and Cheap Trick were among the most popular rock bands the city called its own—even if most of them weren’t from Chicago proper—and there was very little that unified them outside of geography. Blues, jazz, and soul remained vital communities, even if shifting tastes weakened their commercial status, and polka, a reeling musical mutt created by Eastern European immigrants, remained vibrant albeit off the mainstream radar.

Unfortunately, one of the things that attracted national attention to Chicago that year was a novelty record by Chicago proto-shock-jock Steve Dahl. In 1978 he was fired by his long-time employer WDAI after it switched its format from rock to disco. Part of his response was to release “Do You Think I’m Disco” on a small independent country label called Ovation; it was a single that parodied the Rod Stewart hit “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy,” fomenting a reactionary revolt against mainstream disco—Saturday Night Fever, Studio 54, cocaine, and polyester three-piece suits—and it reached #58 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. The single was just part of an anti-disco campaign the DJ had been waging all year. When disco singer Van McCoy, who scored a massive hit in 1975 with “The Hustle,” suffered a fatal heart attack on July 6, Dahl destroyed a copy of the record on air.

The DJs efforts culminated in an event his station WLUP cooked up with Mike Veeck, the marketing director of the Chicago White Sox, dubbed Disco Demolition Night. Fans could get tickets to a doubleheader on July 12 against the Detroit Tigers for just under a buck if they brought a disco record to contribute to an ad-hoc funeral pyre. A giant box was set up in the outfield and filled with the records and explosives, and after the first game, which the Sox lost, Dahl, dressed in military camouflage and wearing a soldier’s helmet, drove a jeep onto the field. He told the capacity crowd, “Now listen—we took all the disco records you brought tonight, we got 'em in a giant box, and we're gonna blow 'em up reeeeeeal goooood." And that’s just what he did.

The crowd—dominated by rock-loving kids more than baseball fans—went berserk, swarming the field in a celebratory haze. It took the Chicago police to clear the field, but the damage to the playing surface was so extreme that the Sox were forced to forfeit the second game. The imagined target of Dahl’s song looked an awful lot like John Travolta’s character in Saturday Night Fever, Tony Manero. The DJ has always said that there was nothing beyond the surface of the stunt beyond a love of rock music, but it was impossible to miss how racism and homophobia fueled the mayhem that night, hardening a divide in popular music that has remained to this day.

Pioneering house DJ Frankie Knuckles famously claimed that “house is disco’s revenge”—words that have proven prescient over time. In 1979 what would eventually be known as house music had officially taken root among a largely gay segment of the city’s black population, through all night parties at juice bars like the Warehouse, founded by New York transplant Robert Williams a couple of years earlier. But like several musical communities that would come to define Chicago in the decades to come, it was in a nascent period, finding its way and developing an aesthetic that eventually would rival the influence of the city’s old blues scene in terms of global impact.

The city’s underground rock scene was even less developed, but its seeds were being sown. In a couple of years DJ and fan Terry Nelson would introduce some of Chicago’s most important punk bands including Naked Raygun, the Effigies, Strike Under, and Silver Abuse on the 1981 live compilation Busted at Oz, released by his imprint Autumn Records, which also put out the first records by goth-leaning post-punk band Da! Looking back on the Dahl fiasco he says, “We didn’t like disco, but that whole thing made us laugh because the rock stuff those kids were into was complete shit.” At the time Nelson had a show on WZRD, the long-running radio station of Northeastern University, that specialized in punk, but he notes there wasn’t much of the music happening in Chicago outside of Silver Abuse, the Cunts, Tutu & the Pirates—who were as much joke band as punk combo—and the Nodes.

Cary Baker happened to be the Ovation Records publicist when the Dahl single was released, but he didn’t have much interest in the record or the music the DJ was championing. He’d recently moved back to the city after graduating from Northern Illinois University in 1978. Baker had omnivorous musical tastes, but while in school his adoration for British Invasion rock led him to the burgeoning power pop scene sprouting up around Chicago’s exurbs. In 1975 he caught Rockford’s Cheap Trick in DeKalb and they turned him into a zealot; he befriend the group and wrote stories about them for local music rags like Illinois Entertainer and Rockford’s Lively Times, which he soon edited. He says, “Cheap Trick were the roots of new wave, and they revolutionized power pop in America.”

Baker, who moved to Los Angeles in 1984 to become publicist for a hot new indie called I.R.S., began writing for Creem, New York Rocker, and Trouser Press and worked tirelessly to promote the new pop sound. In 1978 he formed a short-lived indie called Fiction that released the debut single from the Names—the other power pop band from Rockford at the time—and a couple of records by early Chicago new waver Wazmo Nariz, later signed by Stiff Records and then I.R.S. He financed an early EP by Tutu & the Pirates—whose members were classmates of his at suburban New Trier High School—but he balked on releasing it, returning the master and reimbursing them for studio costs. He also wrote about the regional scene for Greg Shaw’s Bomp, and while in school he got a package from Zion, Illinois containing a copy of Black Vinyl Record, the self-released 1977 debut album by the Shoes. His advocacy led them to record for Bomp, which then led to a three-album stint at Elektra.

But for Baker it wasn’t all as new as it seemed. He points to the late '60s Chicago garage bands who mainlined Merseybeat and reformulated it for the working class Midwest—groups like the Buckinghams, the American Breed, Cryan Shames, and the New Colony Six. In a recent Cheap Trick oral history published by the Chicago Reader, Pezband drummer Mick Rains says, “I think it was the Buckinghams' fault. They played in front of that fountain in Grant Park in 1965, it got in the water, and these kids drank it. It turned every garage in the suburbs into a Fender amp store or a recording studio.” Indeed, by 1979 if there was a single sound that characterized the best Chicago area rock it was power pop: Cheap Trick, Shoes, Off Broadway, and Pezband among others. But by and large those bands didn’t see themselves as new wave acts, and Baker notes that Cheap Trick were thrilled to land tours supporting the likes of Journey and Heart. The group’s first three studio albums for Epic didn’t achieve much success, although “Surrender,” from their 1978 album Heaven Tonight, reached #62 on the singles chart.

But, naturally, Cheap Trick was big in Japan. They toured the country in 1978, were treated like massive rock stars, and a Tokyo concert on that tour was soon released as Cheap Trick Live at Budokan, although only in Japan at first. But demand for the import eventually led Epic to release it in the US and Cheap Trick were no longer a regional band—it went triple platinum and produced a pair of top 40 singles in “I Want You to Want Me” and its cover of the Fats Domino classic “Ain’t That a Shame.” Cheap Trick maintained its love of pure pop, but they loved being rock stars more. Meanwhile, several revolutions were heating up: house would soon be recognized as a concrete style rather than the lifestyle sound it was at time, causing a genuine paradigm shift in pop music, while Chicago’s fierce and scrappy independent spirit would produce one of the most creative and original rock scenes in the country, one that spurned the sort of stardom Cheap Trick had finally attained.

Interview: James Blake and the Pursuit of Happiness

It’s easy to understand where James Blake gets his reputation.

In the six years since his career took off with a major label deal, the British songwriter has become a master of his own style of melancholy, dub-inflected songwriting. His distinct falsetto—first used sparingly amid mysterious electronic tracks, now an inimitable hallmark of his sound—is often warped with reverb and digitization to sound hauntingly lonely, or robotic, or whatever else his meticulously assembled elegies call for.After two critically acclaimed albums’ worth of this, a Mercury Prize, Brit and Grammy nominations, and hundreds of worldwide tour dates, it makes sense that he’s now known as one of music’s most somber sad boys. He gets the same jokes that follow Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon around—you know, the ones that suggest they’re actually magical woodland creatures. (No wonder the two men are now close friends and collaborators.) Blake knows his stone-faced public demeanor—or his phantom forest music videos—hasn’t done much to dispel that image, either.

“There are a lot things I thought I was—and that maybe I tried to portray myself as being—and one of those things was ‘serious,’” the 27-year-old says, emphasizing that last word dismissively, like he no longer believes it even exists. “That wasn't me.”

It’s the middle of April, and Blake is sitting in the afternoon sunshine on a restaurant deck at the end of the Malibu Pier. Wearing a mint-colored floral shirt with birds on it, eating salad and drinking iced coffee, and making dry jokes about the toddlers screaming at the next table, he looks like a man who is perfectly comfortable out in the open, among humans. With his small, round, iridescent sunglasses—a pair that can only be described as “groovy”—he might even seem a little goofy if his tallness didn’t also give him an air of unflappability. Based on appearances, it seems like much has changed in the three years since his last album, 2013’s Overgrown.

During that time, Blake has shared studio time with a cornucopia of top-tier talent: Vernon, Kanye West, Drake, Vince Staples, Rick Rubin, and even the elusive Frank Ocean. And Rubin’s Shangri-La Studios here in Malibu was the birthplace of a good chunk of his new album, The Colour in Anything. Blake says the record is the result of some of the healthiest, most productive years of his adult life. His relaxed attitude today is as new to him as it is to me, and he’s eager to dissect the changes he’s undergone.

“For this record, I just decided that I was going to let people in and allow help,” he says of Colour, which features guest spots from Vernon and psychedelic New Zealander Connan Mockasin, as well as songwriting contributions from Ocean and production from Rubin. It still features the singer’s signature harmonies—those poignant tributes to broken relationships and life in the modern era—while adding more acoustic piano improvisations and introspection. Some songs have him sounding more blatantly heartbroken than ever, and it’s hard to miss the naked woman drawn into the gnarled branches of the album’s illustrated cover. But despite being 75 minutes long—nearly twice the size of Overgrown—the record also feels less obsessed-over. This loose quality is perhaps thanks in part to his newfound openness to collaboration and assistance.

After spending nearly his entire adult life in the spotlight, he’s been making a conscious effort to keep everything in perspective, to get out of his own head and live a normal existence. Whether in the studio with Ocean (who he names as Colour’s biggest influence) or Staples (for whom he’s been producing beats), or back in the outside world catching up on lapsed friendships, Blake has spent the last three years consciously removing himself from the dark, moody hole he dug for himself following his instant success.

And if you believe in karma, you might say this personal evolution has rewarded him: Colour arrives directly after his appearance on Lemonade, Beyoncé’s latest world-stopping pop gambit. In addition to helping pen the record’s opening track, he also co-wrote and sang on the song “Forward,” which shows up at the visual album’s most sobering stretch, as images of the mothers of Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown—each holding a photo of her late son—flash across the screen. Blake has now arrived at a moment in his career where his music resonates powerfully enough to soundtrack the cultural moments of the biggest stars on Earth. And he’s never seen more clearly.

“I listened to my old music and I really didn't sound like a happy person. I wouldn't want to be one of those artists that keeps themselves in a perpetual cycle of anxiety and depression just to extract music from that.”

—James Blake

Pitchfork: How did the Lemonade feature go down?

James Blake: Beyoncé came to the studio, and I was sitting at the piano when I met her. She was just lovely. I came up with something to go with an idea she had; I just embellished her melody. I think the idea was to use some of her lyrics, but I didn't realize that—I misunderstood and did something entirely different from what she wanted. But it didn't matter, because she really liked it, and they ended up using [my version]. Blue Ivy was there, too, which was nice. She was singing along to the song, which was a huge compliment, because kids just don't have any pretense whatsoever.

Had you been in touch with Beyoncé’s people for a while before you actually did the song?

Not for that long. She has very nice people working with her. To be honest, in that world of very, very high-profile musicians and artists, it's quite rare to have a personal touch, because by that point it's kind of a well-oiled machine and sometimes experiences like that can be quite sterile. I enjoy working with somebody that collaborates in the traditional sense, where you actually sit down and make music. I was worried a little bit that it wouldn’t be like that, but I was working with material that she'd made and collaborating with it. Getting to chat with her about it was really nice. I guess that's as good as it gets with somebody as brilliant as her. With somebody at that level, you can never really be sure, just because there's so many people involved in a record, but she's such an accomplished writer and singer.

Did you have any idea where or how your song would fit into the album or film?

None at all. I was pleasantly surprised to find that my song came in at the point that it did, and that she harmonizes with me for a brief moment. The first time I heard that, I got chills. And I found the way it's used in the film really moving, seeing the mothers holding up pictures of their sons that have been killed via police brutality. I was honored.

What has the reaction been like for you? Were people in your life surprised?

Yeah. It just shows you the reach that she has—I had cousins of cousins ringing me. I really hadn't expected it. It's just really flattering.

Was that a coincidence that it came out so close to your own album?

Yeah, it really wasn't planned. I wasn't sure when she was going to release anything. But it’s very good timing, indeed.

How do you view The Colour in Anything in comparison to your previous work?

It's bigger in scope and a byproduct of a lot of change and growing up, really, a lot of self improvement and reflection. My relationship was a catalyst for those kinds of changes; the person I’ve been with for the past year or so really brilliantly held up a mirror to me. I mean, I grew up an only child, and then at 21 I became quite famous—you’re in a petri dish, and people are just peering in on your progress. I feel now as if I can identify with more empathy and relate to people.

You've caught up?

I think that's what it is. A lot of what I'm talking about is very normal for everyone else, because they grew up with brothers and sisters, or have had a very active social life. But I think musicians and artists especially risk falling away from the normal growth. I realized there was something worth saving and fighting for, and that meant looking at myself. It's been really great in the long run, but it was painful.

This record is more expansive that your last, in both the variety of styles you’re playing with and in terms of length. Did you set out to make a more ambitious album this time?

No, it was weird. When you’re living an unstructured life, you can quickly develop self-doubt. You haven't learned the same mechanisms for keeping yourself busy or active, and I slipped into a habit of being quite unproductive. I was making music, but I did all kinds of procrastination, trying to live a normal life, basically. I needed to improve my headspace, so I spent a year trying to improve my mental state. And then, just by doing that, I ended up writing a lot of the best music on the record.

You mentioned you were more open to collaboration this time around as well.

In the middle of recording, I felt like I wasn’t going to finish this record if I didn't get some help and start working with other people. Making a record on your laptop is not the most stimulating process socially. You can really fall into the sinkhole if you're not careful. So I thought, Fuck this, I’m going to spend time with other engineers. The idea came from working with Frank [Ocean], who was a huge inspiration for this record: his process, the way he writes, the strength of what he does, who he is. We became very good friends.

When I was working on some of his music early on, there was this chord progression I didn't like in something that we were making, and I had an idea. A producer was in the room when I was coming up with it, and he was like, “Nah, I think the chords are fine.” I was like, “No, no.” Then he basically said, “This is Frank's music.” And that’s exactly what I hadn’t learned by working on my own all these years; it's the first lesson in producing, to let go. Frank's vision was the only thing that mattered, at the end of the day. If the tables were turned, and Frank were to have a particular opinion about my music, I would take it into consideration, but it's about my gut feeling as well. But learning from that made me want to work with other people on my own projects.

But you're also saying this Frank Ocean record going to be worth the wait, right?

Yes, from what I know. It may be subject to change. He is onto something, he really is.

How did your approach change on this album, musically speaking?

I explored sitting at the piano and singing a lot more. I would talk with Justin Vernon, who is a great producer—a lot of people may not know that about him. He's a good person to talk to. Much like Rick [Rubin], actually. Justin is an incredibly warm man. We've become really good friends. When I first met him, it felt like we had been separated somewhere down the line and were meeting each other again. It was a very strange feeling. In the studio, he would say things like, “Oh man, I love the chords in that track,” and that gave me so much confidence. Singing standing up at a mic with someone else recording was new, too; there never was any time to set up properly before.

You once talked about working with Kanye, but he’s not on the record. Did it not work out?

Something was supposed to happen; I don't really know how to describe how that didn't work out. I wanted Kanye to be on the song "Timeless," but the verse didn’t materialize. I think a huge swath of things happened in his life, and I just stayed out of it. Eventually, the mood of the album changed, and in the end I don't think it would have fit. But I didn't say I was working with Kanye just so people would get interested—I really wanted him to be on it.

Did you actually meet up?

Yes, it was hilarious, because I'm just not used to the kind of environment [he lives in]. So he tells me, "Let's meet in the Hidden Hills." I've never been there—it's almost like a celebrity resort, with a gate and everything. That was one of the most frantic car rides of my life. I had put "Hidden Hills" in the [GPS] and ended up in a farm somewhere. And I remembered some experiences I’ve had with people in America being late and kind of unreliable, and I thought, Man, if Kanye's late for me, it's not going to happen.

And then you were late?

I was twohours late. I got there and was like, "I am so sorry." I was frantic. But he was so cool about it. Really lovely. So, you know, socially, it worked out in the end. It just didn't yield any music. And that's OK.

You have a reputation for making melancholy music. Were you trying to get away from that this time?

I listened to my old music and I really didn't sound like a happy person. It was surprising to find out that I had been fairly unhappy that whole time, and people close to me may not have noticed. I'm not saying I didn't enjoy anything, but those first four years of my career—I'm not sure I remember as much of it that I would like to, in vivid technicolor. Some of it is grayed out. I realized that [when it comes to making music], it wasn't important whether I was happy or sad—it's about sensitivity and your reaction to the world. I wouldn't want to be one of those artists that keeps themselves in a perpetual cycle of anxiety and depression just to extract music from that.

It's a toxic way to live.

Totally. With my first two records, as much as I see music I'm very proud of, I also see a headspace I don't want to be in anymore. I’m happy to be sitting out here really enjoying it. It's all in color.

Has your relationship with people in your life changed as well?

Yeah. What I've noticed is, when people see you become famous, they stop asking you how you are—really, deeply, how you are, not just, “How's the career going?” I mean, “Are you all right?” Because they assume you are. And they stop telling you what happened on their weekend. So it takes a little bit of work to get people to remember that you do really care; just because I went to Brian Eno's house for tea doesn't mean that I don't want to know what happened when you went clubbing on Friday night.

I'm not a dubstep person—

Neither am I.

But do you think making music in that world lends itself to more doom and gloom?

Absolutely. It was so funny, when I was making music like that, I heard a lot of people saying, “Oh, I can't really dance to this, it doesn't have any melodies.” At the time, I was like, “What are you talking about? This is the perfect expression of everything I'm feeling at the moment.” But I now understand why they were saying that. Now I kind of get it.

Longform: Internet Explorers: The Curious Case of Radiohead’s Online Fandom

When longtime Radiohead fans saw the words “True Love Waits” on the tracklist for the band’s new album, they collectively lost their shit. “TRUE LOVE FUCKING WAITS THOM ACTUALLY DID IT THE ABSOLUTE MADMAN,” one user wrote online. The song was a live favorite that had been teased for more than 20 years but never properly recorded, and the existence of a definitive version offered the closure of a long-open loop, like finally discovering what was in Pulp Fiction’s golden briefcase. “It’s been a long journey for us and the band,” reflected another fan. “I feel as if this was their way of saying thanks, thanks for it all.”

The communal release came after months of frenzied speculation on message boards and throughout social media, as followers scrutinized mysterious leaflets, the registration of a new company, and totally humdrum in-studio photos. This zealous anticipatory dance has become typical for new Radiohead albums, igniting warm reminiscences, excitement, and even a little anxiety. One diehard named Megan told me that, over the last few months, she would wake up in the middle of the night and immediately check her phone to see if the record had dropped. She even dreamed about its release—a nightmare, in fact, because her fantasy album turned out to be made up of Radiohead-penned songs performed by other artists. “I was just devastated that it wasn’t them,” she said. “It was pretty ridiculous.”

From a distance, such devotion to a bunch of middle-aged British art rockers could seem a little wild. But in the five years since 2011’s The King of Limbs, Radiohead’s reputation as an iconic band that spans generations, continents, and technological eras has only gotten bigger. These fans now have more ways to discuss the cloud of rumors that constantly surround the band’s activity, allowing for stray theories to percolate into near-certainties as sites like Twitter and Reddit exponentially speed up the spread of information. At this point, there are teenagers Snapchatting selfies with their Radiohead concert tickets as their parents get wistful on Facebook about buying OK Computer the first day it came out.

Radiohead isn’t the only band whose mere gestures get turned into news stories, of course, but they’re unique in that the underlying architecture of their internet fan network has been in place for more than 20 years. As the internet developed, so did Radiohead, and an understanding of the long-running relationship between the two helps explain why people are still willing to devote their waking hours to the pale quintet’s every move. Because once you head down the band’s endless internet rabbit hole, digital ephemera starts to gain purpose, and mistakes turn into clues that make a strange sort of sense.

Consider an Instagram picture of a red moon posted by Radiohead visual artist Stanley Donwood earlier this year, which incited much fan speculation after it was hastily deleted. And then consider the new album’s title: A Moon Shaped Pool. Suddenly, Donwood’s erasure seems like a definite—though admittedly vague—portent, a reason to believe.

Throughout the 1990s, Radiohead thought deeply about the approaching technological age in a way that presaged our modern online era, with its concerns about what all these screens are doing to our brains. “Scrolling up and down, I am born again,” Thom Yorke sang on OK Computer’s “Airbag,” which was written about a car accident, but could also describe the experience of using a message board. Their popularity took root amongst the first wave of internet users, back when the web was more anarchic and undefined, and used primarily by people who felt alienated enough to sit in front of an ugly monitor and post under a pseudonym when almost nobody else was doing it.

Nowadays, we know more than ever about our favorite bands and artists thanks to social media; 20 years ago, though, most bands didn’t even have a website. Radiohead were an exception. But their early online hub was incredibly sparse: a few pages of GIFs and seemingly random text, with little in the way of actual information. No lyrics. No tour dates. No news. It was an allusive vacuum, waiting to be filled.

At the end of 1996, Adriaan Pels was 23 years old and working as a hotel manager in Groningen, Holland, where he grew up. He had an internet connection, which was relatively novel: In that year, less than one percent of the total global population had web access. Pels was looking for something to do online, so he decided to start a website. One inspiration came to mind: Radiohead, a band he’d been hooked on ever since coming across a queasy eruption of a rock song called “My Iron Lung” on the radio and hearing its oddly comforting declaration that “If you're frightened/You can be frightened/You can be, it's OK.” (The group’s breakout 1992 single “Creep” had seemed too much like a novelty to him.)

His new site needed a name. At first he called it Pop Is Dead, after an early single, but that sounded a little lame. In the middle of 1997, he thought of a snippet from “Fitter Happier,” a robo-voiced manifesto from the band’s just-released OK Computer, that seemed to fit, and At Ease went live. Considering its jittery subject, the site’s name was a relatively ironic choice. The calm of the phrase juxtaposed neatly against the profound sentiment on OK Computer that everything was definitely not at ease—that modern times were giving rise to a new sense of alienation, and that the bountiful ’90s could not last. And, practically speaking, “At Ease” was short and started with an “A,” which made it stick out among web rings that indexed fan sites.

Pels detailed his new online hub with hard facts about the band, like the particulars of their discography, which were not easily researchable in a pre-Wikipedia era. He also updated At Ease with news about Radiohead’s productivity, meticulously collecting news items and writing them up as straightforwardly as possible. Occasionally, people would e-mail tips to him. He updated the website when he could, and that was good enough.

Sitting in a Brooklyn cafe, the now 42-year-old Pels looks a bit like the lead singer of the National on an off day in a grey hoodie, beard, and square glasses. Thinking back to his site’s beginnings and how things have changed, he points to a car that drives past us outside the window. “If that car crashes, it will be on the internet five minutes later, or sooner,” he says. “That was much different at the time—it didn't go as fast as it does now.” Another cautionary lyric from OK Computer comes to mind: “Idiot, slow down, slow down.”

Ironically, OK Computer’s wary read of technology may have been most engaging to those already spending more and more time online. The surge of interest in the band drove traffic to the fan sites, including one called Green Plastic, which was started by a 20-year-old named Jonathan Percy in 1997. Like Pels, Percy was attracted to the infinite possibilities of the digital era and saw the internet as the Wild Wild West, or a Choose Your Own Adventure book—an untamed space where anything could happen. And soon enough, such sites became prominent, trusted sources in the swirling world of Radiohead fandom.

In 1998, an MTV affiliate in Europe ran a news item about bands and their fan sites that included Green Plastic. (At the time, Percy’s creation didn’t have its own domain name, so MTV flashed its unwieldy AOL web address.) The attention funneled even more curious listeners to the site, as music fans in general began to migrate away from radio, TV, and magazines. “It kept growing,” Percy recalls.

Within a few years, there were dozens of fan sites devoted to Radiohead. Follow Me Around was founded by Toronto’s Beryl Tomay in the summer of 1997, when she was only 15. Her parents noticed she was spending more time in front of her computer but soon realized she couldn’t be discouraged. “The only time I wasn't really checking it was when I was in class,” she says. “I was pretty obsessed.” In 1999, Miro Bzduch started a site that exclusively catered to fans in his home country of Slovakia. “We didn't have too much exposure to the outside world, so the motivation came from being able to be a part of something bigger,” he says. By 2002, the site was popular enough to justify an English language relaunch called Treefingers.

Meanwhile, the band’s official site started to flesh out. In 1999, it switched from a purposefully opaque K-hole of abstract lyrics and graphics meant to drive fans insane with speculation to a more formal, accessible destination. It was still thin on details, though, and keen to outsource the most time-consuming elements of website management. A page titled “News” read: “Well, obviously if you really wanted news about Radiohead you’d be at some other site that is actually updated more than once a decade. The simple truth is that I don't have any news. But I have found out about some people who do.”

The official site provided links to At Ease, Green Plastic, Follow Me Around, and many others. There was a sincerity and gratitude in this acknowledgment, which was something of a surprise coming from a band often heralded for its obtuse chilliness. A version of the site that came in 2000 added a personal note to its list of links: “These sites have… a flavour far superior to the ‘news’ often found elsewhere. Many thanks to the diligent humans responsible for these pages.”

The release of Kid Adovetailed with Radiohead’s intuitive understanding of the nascent internet culture. Ahead of its arrival in the fall of 2000, the record was streamed for free via a player that any website could embed—the first of its kind—further cementing the link between band and fans. Their official site also launched a message board, where band members would occasionally post, their words highlighted in verified blue.

But just because it was Radiohead’s forum didn’t mean fans would be automatically deferential. In May 2000, someone responded to a message from Yorke by mocking him as a “big star” and accusing him of no longer supporting his local music scene. After a short back-and-forth, the fan asked why he had heard stories of Yorke telling fans to “fuck off” on the street.

Yorke’s answer was grammatically curious but candid: “if i cant handle it then yes. if im fucked up in th head then yes. if i see them again then i would apologise. i am not perfect. i am not very good when people prvoke me. i react. when someone is in you face. interupting you when you are talkign to a loved one. if they are rude. insistent. arrogant and i am not in the mood i will react. if they come up to me in a club pissed out of their head and start drawling away to show off to their mates then i often cant think of much to say. this is why sometimes o dont go out. this is why i often leave the message board. like now. Goodbye.”

Today, even with all the direct avenues opened up by social media, it’s all but impossible to imagine Radiohead ever being as forthcoming about their emotional well-being. Looking back, the post might be read as an attempt to stay relatable in light of the band’s growing fame. “I have a real fucking problem with that,” Yorke once said of the mythology that comes with being in a successful rock band.

At the same time, the way they handled their success couldn’t help but stoke the collective imagination. Nearly every iteration of their official site has been marked by cryptic texts and alien imagery: They are puzzles asking to be solved. As Radiohead’s popularity grew, they never deviated from their aesthetic commitment. The internet was just one more medium for those aesthetics, giving fans more to consider in their devotion. Even their attempts to demystify the process, such as a running diary of the Kid A recording process, contributed to their myth. In acknowledging the fan sites, they teased a deeper connection: When you went to At Ease or Green Plastic, you were reading the same thing Radiohead were reading. Their presence was always known, even when the band itself was absent.

At Ease and Green Plastic also launched message boards that became popular around the turn of the millennium. The posting environment was less exclusive than the official site’s board, where users were careful to maintain their credibility in case a band member dropped by. On the fan sites, there were close readings of the band’s lyrics and slightly conspiratorial discussions over their creative direction. Though Pels and Percy didn’t want to encourage any sense of competition between their sites, their supporters weren’t nearly as nonpartisan. Percy would post a news item and then receive a snide email from an At Ease fan about how his site had been an hour slower, which dimmed his enthusiasm for the passion project.

But such petty sniping was out of his hands and more attributable to the peculiar circadian rhythms driving the behavior of any insular online community. (Fact is, internet users have always been kind of rude.) Meanwhile, Pels and Percy became increasingly elevated as figures of importance within the greater Radiohead scene—online and off. They were approached at shows by people who recognized their photos from the internet. Occasionally, Pels was even asked for his autograph and, one time, he approached Radiohead guitarist Ed O’Brien at an R.E.M. show and introduced himself as the guy who ran At Ease. To his amazement, O’Brien said he knew who he was.

There were other benefits to running websites that so many fans depended on. Pels got to hear an advance copy of Kid A, owing to his friendship with a music journalist who followed At Ease. In the buildup to 2001’s Amnesiac, Percy and Follow Me Around’s Tomay were invited to design content for something called GooglyMinotaur, an AOL Instant Messenger bot that spat out Radiohead information when provoked. Their sites became partners with Ink Blot, a San Francisco-based music magazine that was developing a network of fan sites, and Percy moved out to the West Coast to become a webmaster for the company. Tomay received $20,000 for joining the network, money that went toward her college tuition. They also got VIP tickets to some shows and briefly met the actual members of Radiohead in a casual setting. Before a 2000 show in Toronto, Tomay received the ultimate call out: Before performing “Follow Me Around,” Yorke specifically mentioned her request for the song. “They knew I lived in Canada, and before the concert I put in bold letters at the top of the site’s news section: ‘RADIOHEAD PLEASE PLAY THIS SONG AT THE CONCERT,’” she says. “That was a highlight.”

A connection to the band could also function as a safety net. At one point, Radiohead’s publishing company came after a number of fan sites that hosted the band’s lyrics, threatening to sue over copyright infringement. Percy panicked and reached out to one of his contacts within Radiohead’s camp. Within a day, the issue was entirely resolved, and the lyrics remained.

Such support from an arena rock group was hardly a given in the post-Napster era, when animosity toward the internet’s drastic reinvention of fandom and music culture ran rampant. Yorke, however, loved Napster. In a 2000 interview with Time, he said it encouraged enthusiasm for music “in a way that the industry has long forgotten to do.” So while Radiohead’s songs often took a cold, hard look at technology, the band never forgot the importance of intense fandom, even as their public presence became increasingly withdrawn.

The anticipation for 2003’s Hail to the Thieftook root on the message boards, as traffic to the fan sites continued to shoot upward. The server bills for At Ease leapt from $15 to $700 a month, forcing Pels to put ads on the site and solicit fans for money to help with hosting fees. Around this time, Tomay stopped updating Follow Me Around as frequently. She was starting college, and the combined commitments of her course work and social life took hold. Bzduch shuttered his site, too.

At Ease and Green Plastic still flourished, but its founders’ schedules were also growing more complicated. Aside from his work with At Ease, Pels started doing graphic design for the Amsterdam label Excelsior Recordings. Meanwhile, the bursting of the dotcom bubble forced Ink Blot to kill its network of music sites, but Percy used his connections to start working at an advertising agency in San Francisco. Both men were no longer bored young adults with hours to burn. They were in their early 30s. They had lives.

Radiohead have always worn a shroud of mystery, but they became even more unpredictable as the years went on. Their 2007 album In Rainbowswas released with only 10 days notice, and fans were asked to pay whatever they wanted to hear it. Around this time, Green Plastic’s traffic hit its peak, and In Rainbows eventually became the band’s best-selling record since OK Computer, moving three million copies worldwide. It proved Radiohead could release a record on the most secretive terms, basically for free, and still be wildly successful, even as industry profits continued to plummet. They were able to take that risk partly due to the fan sites and their communities, which offered a solid bedrock of support.

As social media started to expand, Radiohead continued to retreat. They did no interviews or touring in the buildup to 2011’s The King of Limbs and teased A Moon Shaped Pool only as it was about to be released. Their popularity became increasingly untethered from the typical formalities of record promotion, placing them on the same level as Beyoncé and Kanye West. They managed to avoid the frivolities of mainstream, corporate celebrity culture, too: It’s impossible to think of Thom Yorke making a cameo on “The Muppets,” or Jonny Greenwood joining in an all-star band at the Grammys.

Around 2010, Percy grew tired of maintaining Green Plastic. The message board was still active, but there hadn’t been regular updates for years. He met the woman who would become his wife in 2011, but he didn’t tell her he had once run one of the biggest websites for one of the biggest bands in the world until a couple of years into their relationship. The site remained partly as a shrine to his past, as well as Radiohead’s. “I’ve had a lot of people offer to buy it from me and I’ve always been hesitant,” he says. “It’s my baby.”

Pels continued to update At Ease regularly through 2013, drawing the site’s highest-ever single day traffic—421,971 pageviews—on February 18, 2011, the day The King of Limbs was released. But his updates ceased, too. A few years before, he had moved to New York City with his wife, who he met through the At Ease message boards. He was working full-time, and there wasn’t much new to say about Radiohead, anyway. “I’m still planning to get things running pretty soon again, but work's been crazy as well,” he told me in March. Weeks later, the site hadn’t been updated.

Even though these homegrown fan sites have largely lapsed, people are still poring over Radiohead’s every move. A general interest site like Reddit now provides a similar service for the nearly 40,000 fans currently subscribed to the band’s subreddit, and the rise of up-to-the-second news sites and social media has generally made fan sites a curio of a bygone age. Instead of a Pels or a Percy curating updates during their downtime at work, there’s a democratic network of devotees contributing what they can in real-time.

Radiohead’s own website eventually stopped linking to the fan sites. The message board remains, but its intentionally archaic drop-down format could appeal to only the most tenured users, who now mostly circulate in-jokes that are impenetrable to outsiders. In this way, the circle of life continues: I spoke with one fan who said he joined At Ease around 2003 because the band’s official message board seemed too tight-knit, while another said he preferred Reddit to At Ease because it’s far more accessible and not as prickly toward newcomers. In fact, At Ease is currently highly selective when it comes to accepting new members. (There was a recent problem with some trolls.)

Both the At Ease and Reddit forums currently contain plenty of discussion about A Moon Shaped Pool, but the difference involves a sense of history: On At Ease, there are allusions made to memorably irritating users, power-hungry moderators, deleted posts, and members who died and are remembered by their usernames. It’s a web of connections woven over nearly 20 years.

In the days preceding the new album’s release, both Pels and Percy began updating At Ease and Green Plastic to reflect the news. Percy wrote, “It’s been a while, hasn’t it?”

A week before A Moon Shaped Pool came out, Radiohead erased their internet presence, whiting out their official site and deleting their tweets and Facebook posts. The symbolism couldn’t be overlooked: It was their attempt at re-emerging from the ether, a fresh start for a band that has surely wondered how to stay restive as its legacy has grown.

But the gesture could only be symbolic. They couldn’t erase At Ease, Green Plastic, or the hundreds of thousands of connections made through places like them. It’s too glib to say Radiohead wouldn’t have become such an institution without the internet and fan sites, but their career trajectory surely would have looked a lot different had they promoted their music the traditional offline way. And even if the band disappeared completely, it’s nice to imagine the message boards continuing to thrive, adding more layers to a shared history that’s gone way beyond what Radiohead might have thought about when they made songs about the importance of staying human in an increasingly digitized world. There will always be someone on the other side of the screen.

5-10-15-20: The Music That Made Diamanda Galás

Rising: Inga: Outsider Jazz for Modern Times

Longform: The Dark Art of Mastering Music

According to many Metallica devotees, the official version of the band’s 2008 record Death Magnetic is not the one worth listening to. Upon the album’s release, fan forums exploded in disgust, choked with complaints that the songs sounded shrill, distorted, ear-splitting. These listeners liked the music and the songwriting, but everything was so loud they couldn’t really hear anything. There was no nuance. Their ears hurt. And these are Metallica fans—people ostensibly undeterred by extremity. But this was too much.

The consensus seemed to be that Death Magnetic was a good record that sounded like shit. That the whole thing was drastically over-compressed, eliminating any sort of dynamic range. That it had been ruined in mastering. Eventually, more than 12,000 fans signed a petition in protest of the “unlistenable” product, and a mass mail-back-a-thon of CDs commenced. The whole episode provoked a series of questions, not just about what had gone wrong with Death Magnetic but about the craft in question: What is mastering, exactly? How does it work? Beyond the engineers themselves, almost no one seems to know.

Generally speaking, an album passes through many hands before reaching yours. Some of them you already know about—the musicians, of course, and the producer, who acts as a collaborator and shepherd through the creative process; the audio engineers who record songs in multiple takes, usually tracking each sonic element separately. These individual tracks are then delivered to a mixing engineer who combines the best takes, adds effects, and puts them back together into a coherent song.

When the mix is finished, and the album is more or less complete, it’s sent to a mastering engineer—which is the point where general knowledge of what’s happening to the music ends. There is the sense that a mastering engineer can save or, occasionally, ruin an album, but even musicians themselves typically know only the vaguest sketches of what’s actually being done. If rock stars are the sex gods of music, mastering engineers are its druids, the ones who work methodically and meticulously, and to whom people come for mystical wisdom and blessing.

“It’s such a dark art,” says M.C. Schmidt, one half of the experimental electronic duo Matmos. His partner, Drew Daniel, agrees. “It’s this mysterious process that a lot of musicians don’t understand, including us.”