![Articles: Der Klang Der Familie: Berlin, Techno and the Fall of the Wall]()

Photos by Oliver Wia

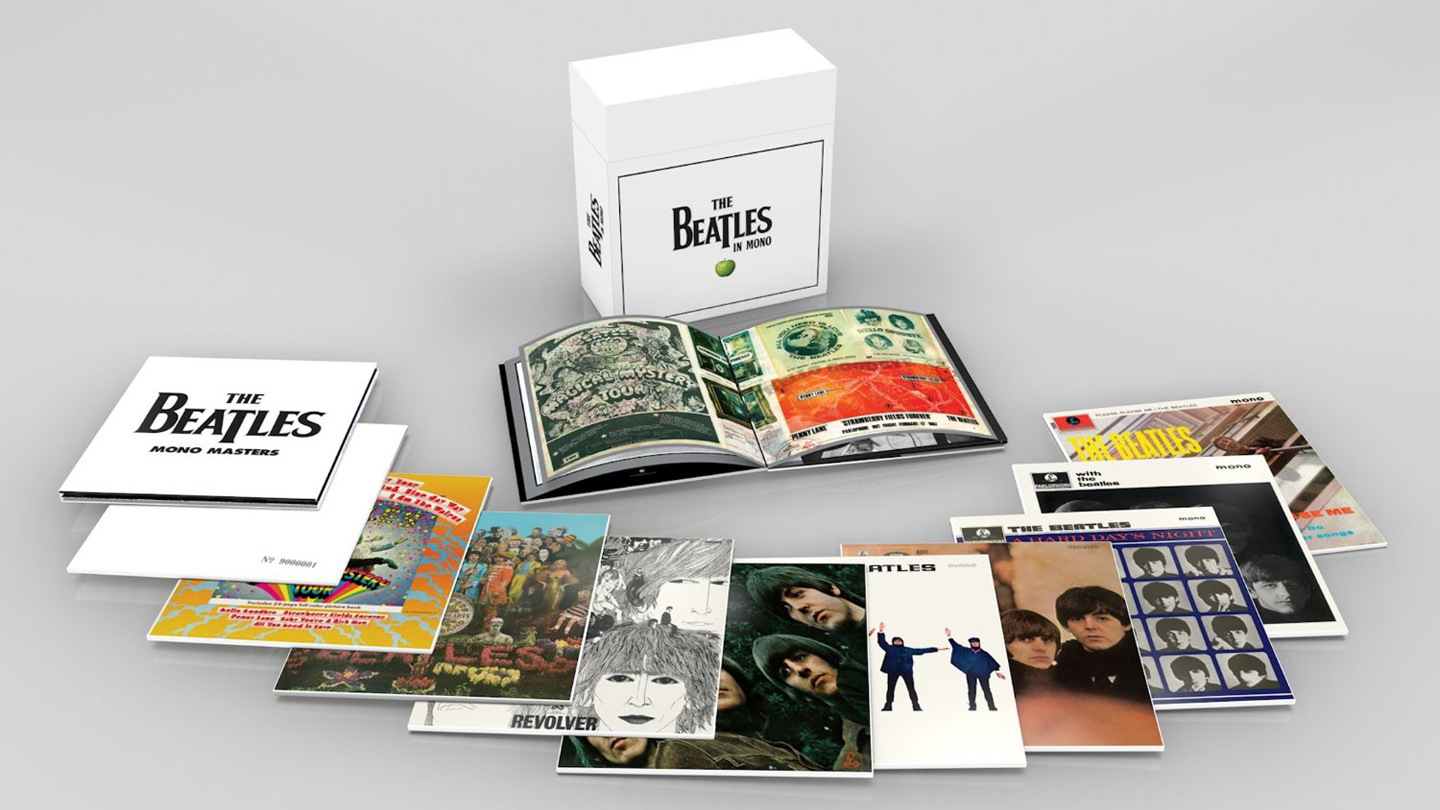

Last weekend, Germany celebrated the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the world celebrated with them. In addition to the obvious world-historical repercussions of the event, the Mauerfall, as it's known in Germany, also had an enormous impact on the state of popular music. The fall of the Wall and the subsequent reunification of the two Berlins (and, moreover, the sudden availability of so much abandoned real estate) set the stage for the emergence of Berlin's techno culture: lawless parties in dank basements with minimal décor and punishingly loud systems. The empathic qualities of MDMA, meanwhile, helped smooth the frictions of reunification, as East partied with West for the first time.

That aesthetic and that ethic, DIY to the core, continue to inspire techno's vanguard the world over, providing a crucial counterbalance to corporate EDM. In fact, Berlin techno has also proved to be very good business. From underground spaces like ://about blank to celebrated temples like Tresor and Berghain, Berlin's array of clubs has contributed to the city's status as Europe's nightlife capital. Tresor founder Dimitri Hegemann is even considering buying the abandoned Fisher Body plant in Detroit, techno's spiritual home, and developing a multi-story club there.

The causal relationship between the Wall coming down and the explosion of techno culture is at the heart of 2012’s Der Klang der Familie, Felix Denk and Sven von Thülen's oral history of Berlin's techno scene, which is now available in English.

"It was basically pure coincidence," they write in the book's preface. "This new, raw, stark machine music appeared—and then the Wall came down. In East Berlin, the administration collapsed; the former GDR capital became a 'temporary autonomous zone.' Suddenly, there were all these spaces to discover: a panzer chamber in the dusty no man’s land of the former death strip, a World War II bunker, a decommissioned soap factory on the Spree, a transformer station opposite the erstwhile Reich Ministry of Aviation. People were dancing at all these sites rejected by recent history, to a music virtually reinvented from week to week."

Piecing together interviews with a wide range of party promoters, DJs, musicians, and scenesters, Denk and von Thülen—editors at Zitty and De:Bug, respectively—recount the story of Berlin techno from the 1980s through the late 1990s: Ufo, E-Werk, Tresor, the Berlin-Detroit connection, Loveparade, and more.

In the chapter excerpted here, those who were there recount the origins of Tresor—Europe's most iconic techno club, hidden behind meter-thick walls in the basement vault of a disused department store in the former East Berlin. —Philip Sherburne

Listen to 30 tracks that got heavy play at Tresor during its early years with this YouTube playlist from Berlin's DJ Rok:

Party at the End of the World

DIMITRI HEGEMANN [Tresor co-founder]: The original UFO [club] had been in a dingy basement. That's where we'd come from and that's where we wanted to return.

JOHNNIE STIELER [Tresor co-founder]: [Co-founder] Achim [Kohlberger] and Dimitri put the idea of starting a club together in my head. That was the dream. I was manic and threw myself into it full throttle, which wasn't easy with those two. They were suffering from the Berlin disease, a kind of particularly absurd punk that could also be electronic—something like Die Tödliche Doris. But it also denoted a particular way of life. Mostly, it consisted of never getting anything done, sitting around somewhere with dirty fingernails and no money hoping that someone would come along with another joint. Complete lethargy. Achim and Dimitri's office—insofar as you could call it that—consisted of two army desks littered with papers. Achim crouched on an old swivel chair on which only he could sit. You had to sit in a very specific position, otherwise you'd fall off. He sat there for years without moving—the epitome of the Berlin disease. Take the fall of the Wall, for example: Dimitri opened the door, saw the Trabbis, closed the door again and lay down in bed, coat and all.

TANITH [Resident DJ, Ufo and Tresor]: When Ufo closed, it was clear that any new club would have to be in East Berlin. Tacheles and Obst und Gemüse had opened right after the Wall came down. Everything was slowly migrating. No one was interested in the West anymore.

DIMITRI HEGEMANN: There wasn't a square meter free in West Berlin.

JOHNNIE STIELER: Achim and Dimitri couldn't really get their asses in gear. It took a huge amount of effort to get them out of the office or even just out of bed before noon. “If we're gonna find something, we have to look,” I always told them. I usually headed out with Achim. We were the first to scour the East for locations. The others intended to, maybe, but they had to watch a little more TV first or explore East Berlin more generally. They had no guide, after all, and when they got out at Friedrichstraβe [subway station], they had no idea where to go. And the way West Berlin scenesters dressed back then, no East Berliner would dream of helping them. They'd take one look at them in their bomber jackets and feign muteness. But from the summer of 1990 on, we were searching systematically. There were plenty of spaces. Old public buildings, former ministries in Stalinist architecture. We wanted to go in everywhere, but there was always some custodian with a Saxon accent. Everything was caught in this tension between reunification and new beginning. There was the D-mark, but otherwise nothing. Nobody knew what was going on. But in Mitte, I noticed even back then, there were these Stasi-type notaries everywhere trading in real estate. They were all sitting around there, selling stuff under the table. They, for their part, knew exactly what was going on.

DIMITRI HEGEMANN: Leipziger Straβe was a single-lane street back then, and there was always traffic. Johnnie and Achim stood there, stuck in their Mercedes on the way to Alexanderplatz, bored stiff until Johnnie pointed to an old storefront and asked, “What about that place?” So they pulled over to take a closer look.

JOHNNIE STIELER: I had to go see a Stasi superintendent for the key. He worked at the East German diplomatic services agency. The old boss wasn't working anymore, so instead, there was this young administrator. From North Rhine-Westphalia, I think. A mid-level pencil pusher in the mood for adventure. I had more than enough self-confidence back then and told him up front that we wanted to rent the place. He sat there at his desk with a look that just said, “Excuse me?” Once he'd recovered, he gave it to us straight: no water, no electricity, no gas, no nothing. What did we want to do there anyway? “A gallery with a bar area,” I said—an elastic gastronomy term convenient for such places. They used it in West Berlin too.

ALEXANDRA DROENER [Tresor manager; E-werk bouncer and booker]: Everyone used that trick. Every phone booth back then was a gallery with bar.

DIMITRI HEGEMANN: The office where we could have applied for a permit didn't exist. It was simply not occupied.

JOHNNIE STIELER: So the administrator guy called the superintendent, and we went right over and checked the place out. When we said we wanted to come back with friends for another look, he just left us his enormous key ring. He'd already checked out. For him, as for so many others, it felt like everything was over. He'd have given me his shoes if I had asked. And so there we were.

DIMITRI HEGEMANN: We'd actually been looking for something above ground. But the basement was the big surprise.

JOHNNIE STIELER: There was a door that had been closed off and painted over and a bookcase standing in front of it. We moved the bookcase aside, jiggled at the door, which was unlocked, and looked down the stairs. I thought, “Well this looks promising.”

DIMITRI HEGEMANN: The stairs led down to the basement.

JOHNNIE STIELER: Then we went down into this slippery stalactite cave with our lighters and after fumbling around in the dark for a bit, we eventually found the door to the vault. It was incredible.

![]() Inside Tresor

Inside Tresor

DIMITRI HEGEMANN: When we came through the open steel door into the vault with those rusty safe deposit boxes, it was immediately clear to all of us: The search is over!

JOHNNIE STIELER: That must be what it feels like to find an Aztec treasure. None of us said a word. We just walked around in silence with our lighters. Then, very slowly, we made our way back up the stairs. It wasn't until we were back in the car that we started talking again.

DIMITRI HEGEMANN: That night, we went back with Rok.

ROK [Resident DJ, Ufo and Tresor]:We drove over, and it was really just a hole in the ground. And then we were standing down there with just a halogen lamp, and he said, “This is it.” Then he asked me what we should call the club. “Tresor [Vault],” I said. Because that's exactly what it looked like. No great flash of inspiration.

DIMITRI HEGEMANN: Johnnie took one of the door bolts with him and used it to create the logo on our computer at the Fischlabor.

![]()

JOHNNIE STIELER: We got a lease pretty quickly. The guy from the agency had got hold of a kind of standard contract. It said it was valid until any sort of construction project began. Outstanding. But then he came with the news that we'd need a security deposit. Achim, Dimitri and I just stood there. We must have looked like the Marx Brothers. None of us had any money. So I asked my mother. She's a professor, and she went straight to her bank and told them that she was Professor So-and-So and that she needed a bank guarantee. And the guy sitting there—he'd probably been there maybe eight weeks—just looked at her and said, “A bank guarantee? Where do we keep that form?” Without my mother, there would never have been any club. They wanted three months' rent for the deposit, a huge amount of money back then. But the guy at the bank set up a guarantee for my mother without batting an eyelid. And so we signed the lease. Rent was 1,600 marks [$1,020, based on current exchange rate].

REGINA BAER [Tresor manager]:When Dimitri showed me the place for the first time, I almost fell over. You weren't expecting anything, and you really had to use your imagination to envision the space as a club. I mean, there wasn't even electricity. We were standing there on the ground floor, and Dimitri pressed a lighter into my hand. Then we went down into the basement, where everything was damp and nasty, and Dimitri was all, “This is the bar, and back there is the dance floor.” I just kept saying, “Leave everything as it is, leave everything as it is. You just have to clear out all the rubble.”

DIMITRI HEGEMANN: Regina was put in charge of the renovation, though she didn't have any more idea than I did how it all worked with building permits and stuff like that. We had these guerilla tactics: just open the door, turn on the lamp, and off you go.

REGINA BAER: Dimitri had wanted to impress me with the space. And he succeeded. After that, we were together.

ALEXANDRA DROENER: When I came onboard, the renovations were already underway. They recruited me because I'd proven myself as a barkeeper at the Fischlabor. My bookkeeping was always right. Or usually right. And I never lost the key. Aside from my reliability, there was a second reason: I was the team raver. Dimitri and Achim knew I'd do everything there anyway because I loved the music so much. At some point, I drove to Tresor with Achim. They all had these RAF Mercedes with a couch up front. When we got there, there were these people standing around with masks and hard hats, totally covered in dust. Someone came out of a hole with a wheelbarrow. It looked like they were undertaking a mission to Mars.

![]() Dancers at Tresor

Dancers at Tresor

TANITH: The walls were over a meter [3.3 feet] thick. Nothing got through them. The world could have ended, an atomic bomb could have been dropped, and you'd still be partying down there.

CLÉ [Resident DJ, E-werk]: Achim and Dimitri had been firing up Terrible and me the whole time with their euphoric talk. When we went over to take a look during the renovation, we were immediately ignited. The space was just screaming to be turned into a club. There was something dark about it, forbidden.

TERRIBLE [Resident DJ, Tresor/Globus]: At the beginning, there were always these jokes like, “Dimitri, we found a tunnel here. It leads to the Führerbunker.”

TANITH: And ridiculous rumors like, “I left that place with a cough. During the War, they stored poison down there. There's fungus inside, it being so damp and all.”

ALEXANDRA DROENER: The Treuhand was across the street, and there were always security guards around. It was a dump. Leipziger Platz was one big wasteland. There was nothing there. Absolutely nothing. Rocks, debris, a fence here and there. You can't imagine it today. The buildings were derelict. The odd tower block built in the '80s. Like a ghost town. Like after World War II. A real zerohour atmosphere.

ROK: It was a desert in the middle of the city. The Wall was right there, and you still felt the division.

TANITH: Achim thought it was well-located businesswise. In the East, but right on the border to the West. Easy to get to.

ALEXANDRA DROENER: Coming to this place from the aseptic Ufo at Kleistpark with its illuminated dance floor—a real disco, you know—was just crazy. It wasn't a question of if but when: When can we start and how loud can we turn up the music? You knew you were underground, in a vault, surrounded by steel walls—it was the greatest. It was a hell of a thrill to be dancing in the ruins of this bank.

REGINA BAER: In the vault, there were these lockers for suitcases. I checked in old phone books at the library to find out what had been located at Leipziger Straβe 126a before the Wall went up.

JOHNNIE STIELER: It was a strange building with a very strange history. Before the War, it was the Wertheim department store. That went all the way to house number 126a, where there was a travel agency. Globus Bank belonged to that travel agency. We even found some Globus Bank stuff lying around. And then those safe deposit boxes where various things were stored. After the War, the aboveground rooms housed the first duty-free shop. As such, it came pretty quickly under the administration of the service office for foreign missions. In other words, it had Stasi written all over it.

REGINA BAER: Next door was this company called Intourist. It was supposedly an East German travel agency, but really it was more of a Russian import-export thing. You could watch as they established themselves and became successful. At first, it was Russian army jeeps and soldiers in uniform—in and out all the time, like clockwork. You always had the feeling you didn't want to know what kind of deals were being made in there or what all was being sold. Later, you'd see the same jeeps, but the guys sitting in them were more casual, dressed in shell suits. Before long, the jeeps were repainted, and you could no longer tell they'd once been military vehicles. And suddenly, the guys were all wearing suits.

JOHNNIE STIELER: Then at some point, they shut up shop. But they must have still been doing something in there because they had an intact phone. It was connected to the so-called S-net, a special tap-proof network, and it worked, too. We used to make calls on it. There were also bags with customs seals, and the attic was littered with bank notes. I discovered them when I went up to check out the roof—1,600 East German marks strewn all over the floor as though someone had simply thrown them away.

DIMITRI HEGEMANN: When we started renovations in December of 1990, we always made sure Regina had enough workers. Whoever happened to be available. The Space Cowboys, for example, Danielle de Picciotto's band. They were coming from their rehearsal room and wanted to know what we were up to. So we put them to work.

ALEXANDRA DROENER: When I arrived with Achim, they put me in some protective gear. Wrap a kerchief, put on a mask, and down we went. The old deposit boxes were covered in a layer of rust as thick as your finger. We cleaned out each one with a steel brush.

JOHNNIE STIELER: I basically never left. Running around the whole time, doing one thing or the other, overseeing the workers. It was freezing down there, sure. But when you're as manic as I was, it doesn't matter. I spent days going over all the rooms again and digging through the debris. The renovations lasted three months. We didn't even have water because the pipes were always frozen.

DIMITRI HEGEMANN: I had this theory that since we were in East Berlin, we also had to contract a company from East Berlin.

REGINA BAER: We thought West Berlin electricians would take one look at the cables and installations and throw up their hands. The power lines were old East German lines; they couldn't handle anything. They fried often—a real fire hazard. You could sit there and watch the sparks fly.

DIMITRI HEGEMANN: So we hired Hummel, this company from Köpenick [in East Berlin], to build our bathroom facilities. We figured they'd just install a water pipe and that would be that. But it wasn't so simple. And Hummel always knocked off early. Very early.

REGINA BAER: What we didn't know was that plumbers in the East were worth their weight in gold. They were even worse than the ones in the West. They promised us they'd finish the job, then secretly cleared out and called it a day around two p.m.—it was Friday, after all. They didn't give a shit that the toilets still didn't work on opening night. And there was no way to reach them either since they didn't have a phone. Neither did we. Everything else worked, more or less, but there was no water.

DIMITRI HEGEMANN: So then we got a check for 150 marks and picked up a hydrant. In the basement, there was a pipe that connected to the main line on Leipziger Straβe. So we tried to hook it up. It was completely hopeless. We desperately needed a pipe wrench, but none of us had one. Tresor almost didn't open because of that pipe wrench. But then I improvised, jamming one pipe into the other to make some sort of construction, then wrapping the whole thing over and over with duct tape. Finally I shouted, “Let it run!” It was leaking everywhere and I looked like hell, but eventually I heard the shouts from above: “Water!”

JOHNNIE STIELER: We were literally tightening the last screw when the doors opened. I think the electrician worked 72 hours straight before the opening. The bar had to be built. We brought in the booze at the end. And finally, the sound system.

![]() Detroit DJ Jeff Mills, Dimitri Hegemann, and French DJ Laurent Garnier at Tresor

Detroit DJ Jeff Mills, Dimitri Hegemann, and French DJ Laurent Garnier at Tresor

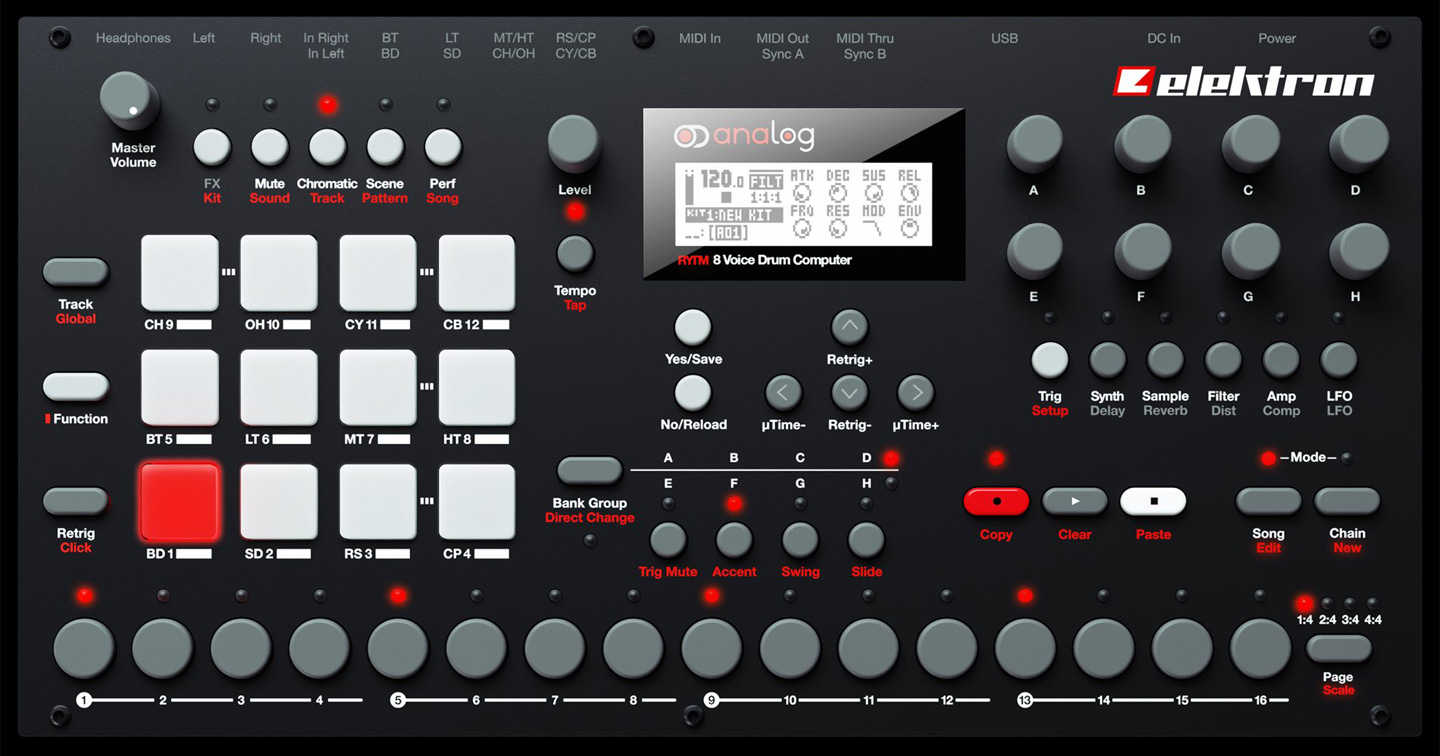

TANITH: We DJs tested it immediately, of course. And it sounded exactly the way I wanted techno to sound. Back then, I wanted to play as hard as possible. Dimitri and Achim wanted it a bit softer; they tried to get me to play house. That's how it had been at Ufo. Rok also played hard when he was allowed to do what he wanted. So for both of us, it was clear right away: house? Here? Forget it. It was hard techno all the way. I played “Little Fluffy Clouds” by the Orb as a test. It sounded like a drone symphony. Nothing fluffy about it.

JONZON [Resident DJ, Ufo, Planet, Tresor]: The first time I dropped the needle on a record there at full volume, I was immediately impressed by the cracking. It was almost scary. We were pretty loud. But that's the way it had to be. The space dictated the brutal sound.

ALEXANDRA DROENER: Later on, there were all sorts of clubs, but none of them had the rawness that became so intertwined with this music.

JOHNNIE STIELER: The sound seemed completely normal and reasonable to me the way it was. But that probably had to do with the fact that I'd spent so much time down there. I practically lived there. When you furnish your apartment, you're not surprised by how it looks in the end. I'd been there from the very first cable and observed every step of the way. It didn't seem all that brutal to me. In fact, I always thought there wasn't nearly enough bass.

REGINA BAER: There's this nice story about Tanith, how he stood on the dance floor and cranked up the system full blast. When his jeans started flapping, he called it 1T.

DIMITRI HEGEMANN: The space was immediately approved. It clicked right away. The music, the intensity, the sweat, the shouting. It was exactly how I'd always imagined the Blue Note in the early jazz days.

JOHNNIE STIELER: We weren't really nervous before the opening. But after a certain point, my anticipation could not have been higher.

ALEXANDRA DROENER: Those were the days when there was nothing. No Internet, no cellphones. Andreas Rossmann alone always had one of those big portable car phones with him. So of course the channels were different. You always had to spread the word. The Fischlabor was Facebook—the bar you went to if you were cool.

TANITH: There were no posters. Monika Dietl announced on her show that something big was coming, but she didn't reveal an address. And then there was the Party Line. Wolle had organized it after Ufo closed. But he didn't have a phone connection in East Berlin, so he abused Roland 128 bpm's phone and connected an answering machine to it. All the dates and times were announced on it.

WOLLE XDP [East German breakdance champion]: The Party Line was supposed to replace flyer distribution. But it wasn't enough if it was just for Tekknozid, which is why anyone throwing a party could use it. The hardest part was recording the message. Submission deadline was Thursday by one p.m.. I would go to a phone booth in West Berlin and listen to the messages, then record one remotely myself. I was always terrified of making a mistake and having to start all over again. Starting at three p.m., the new announcement was available. After that, the line was always busy.

MIJK VAN DIJK [DJ]: When the second Ufo closed, I had no idea where to go anymore. Then Johnnie Stieler hinted that a new place would be opening in two or three weeks.

JOHNNIE STIELER: Every day, there were 20 people who wanted to see the place. Musicians, DJs, their friends. Right away, it was making waves. There was an unbelievable amount of interest. We didn't need to advertise at all, word just got around.

TANITH: For me, the period around '89/'90 was a bit of a leaden time. Aside from Tekknozid, I found it pretty depressing. There were no clubs, the scene was stagnating and stewing in its own juices. I didn't have much hope for the future. But that all changed with Tresor—overnight.

ALEXANDRA DROENER: On opening night, we worked right up to the last minute, painting walls, mounting lights. We opened at around 11 p.m.. Walls wet, black paint on the ceiling. Downstairs, we hadn't even painted at all. I'd wanted to go home first, but I lived in Schöneberg, and that was too far. So we said “fuck it” and didn't change, just stayed in our silly painter's overalls, which you could buy for five marks.

REGINA BAER: We all looked like shit. And Alexandra and I didn't have any clean clothes to change into, just our overalls. So we put them on over our dirty clothes. The next week, people showed up wearing overalls just like those.

ALEXANDRA DROENER: We probably painted each other as well. We were just kids, and we were excited. Achim and Dimitri were grown-ups; they played it cool. I was jumping up and down, hyper. Totally stressed out, happy, raving mad—all at the same time.

REGINA BAER: When we finally finished, much too late, we went out into the dark. Outside, there was just a single light bulb, a dim little thing above the door, and there were all these people standing there waiting. The entire parking lot was full of people, all just standing there politely, waiting for us to let them in.

ALEXANDRA DROENER: There were people in cowboy boots, in sneakers, in suits.

REGINA BAER: Some women had missed the mark and turned up in heels.

ALEXANDRA DROENER: There were some industrial types like Paul Browse. Gabi Delgado from D.A.F. It was a strange West Berlin mix, a pre-reunification mix. And then there were the East Berliners, too. But no casual clubbers. It was eccentrics only. A crazy personality show.

![]()

REGINA BAER: The first ones there, I'd have liked to throw right back out. They were Johnnie's friends, East Berlin hooligans, or at least that's how I immediately rated them. Real bruisers. When I saw them I thought, “If this is my clientele, I'm quitting right now.”

ALEXANDRA DROENER: Johnnie had a lot of legacies we knew nothing about. He'd been very active in East Berlin, something to do with the punk scene. Somehow, we also knew he was a hooligan.

REGINA BAER: I went up to the guys and told them to leave, which of course they didn't appreciate. They got pretty fresh right away—“who did I think I was?” and so on. There was a brief verbal altercation, and then they left.

JOHNNIE STIELER: Some of them, given their political views, would not necessarily have joined the socialist student association in which I was active at university. But they were friends of mine and they were happy when they were at Tresor and didn't cause any trouble.

UWE REINEKE [Raver, EFA Distribution staffer]: I got there very early. Jonzon was supposed to DJ, and I'd given him a lift. There were maybe three other people inside. We were standing around downstairs, and it was freezing cold. No need for a fog machine. I was surprised. What is this place? It looked really grim. Still damp, too.

KATI SCHWIND [Love Parade organizer, EFA Distribution staffer]: I went right downstairs, through the puddles, past the wooden wall, and arrived at this room that glittered with rust. My jaw just hung open. It was at least as great as walking into the control room at the e-werk. You could feel the history of the building.

STEFAN SCHVANKE [Promoter, rave activist]: The space seemed as big to me as an underground garage at first. I thought, “They'll never get this full. They'll put up curtains next weekend so it doesn't seem so vast.”

ALEXANDRA DROENER: At first, there was a lot of standing around, a lot of looking around and a whole lot of talking. And on top of that, the music at full blast. Some people didn't even realize that the actual club was down in the basement. They were in the Globus Bar the whole time, nothing but a boombox up among the glasses behind the bar. A lot of them were part of that lean-against-the-bar generation. Long-haired men in leather jackets, groupies, people in bands, rock‘n'roll people. There were a few ravers too, but not that many yet. The core from Ufo. People who were way ahead in terms of style. They looked like the '90s people in London—flats, Mercedes-logo necklaces, vests, crop tops.

TILMAN BREMBS [Tresor cleaner, photographer]: As West Berlin kids, we were always hanging out at Cha Cha. At some point, a guy came along and said there was a new club at Potsdamer Platz. We took a taxi over, and then there we were in the Globus Bar. Alright. New club—not bad. Then out of nowhere, a sweat-soaked person came along, glowing with heat, and said, “Hey, have you been downstairs yet?” We went down and were completely blown away. And it's not like we were from the boonies. We weren't so easily impressed.

MARK ERNESTUS [Basic Channel/Hard Wax cofounder]: At Tresor, it was immediately clear: This is our place, this is where the music belongs, and everything is defined purely by the music.

TILMAN BREMBS: This unconditional surrender to the music, the soundscape—that's what made the difference. Before, you were always a bystander at clubs. If you listened to hip-hop or downbeat, maybe you were on the dance floor every now and then, but you were worrying about it more the whole time. At Tresor, that simply wasn't possible. You came in and were right in the middle of the inferno. It had a very different intensity. You had to participate—or go home. We went dutifully back to the others at Cha Cha and raved about it. They had no idea what we were on about. In typical West Berlin style, they acted unimpressed and didn't believe a word. Then slowly, one after the other, they came with us. Inevitably, you grew apart from the ones who weren't into it.

![]() Loveparade founder Dr. Motte at Tresor

Loveparade founder Dr. Motte at Tresor

JOHNNIE STIELER: After the opening, I took the subway back to Lichtenberg. Quite honestly, I was glad it was over and that we'd managed to pull it off. Everything at my place stunk of Tresor. A very specific musty smell. It only existed at Tresor, nowhere else. It was because of the thickness of the walls. I mean, we're talking five-foot-thick concrete. The air was unbelievable. Despite the ventilation, it was always the same. It was just the Tresor smell.

ALEXANDRA DROENER: The first night was really, really great. But afterwards, there was a slump. After an opening, you first start to realize everything that still needs to be done. Everything that's not working. The toilets were devastated, of course. That was the everlasting issue.

JOHNNIE STIELER: At the beginning, it was like spinning plates. We ran around trying to make sure the whole thing kept running. A week was like a year. A day was a month. Every day we were open was somehow a different universe. We had our DJ crew together right from the start: Rok, Jonzon, Tanith and Roland 128 bpm. That part was obvious—they had the sound.

REGINA BAER: It was basically just disaster management. Tresor was forever a construction site. Always. We did what we could. The Wasserwerke Ost [GDR waterworks] no longer existed. There was just one waterworks for all of Berlin now, so I had to go to the West German water authority. They said I could definitely get hooked up to the water supply, I just needed to bring them blueprints showing where the pipes ran. I could get the documents at the former East German waterworks.

It was somewhere behind Wuhlheide [park in East Berlin]. Bleak. Nothing but a few GDR trailers standing around. A big open space. I knocked on the door of each trailer—they were all open, but not a soul was inside. Eventually, I found someone who could help me. He led me to yet another trailer and handed me a tube with a big plan of the site. I was over the moon—that is, until I tried to take some pictures of it. There was nothing on it. Completely blank. I thought they were jerking me around. But the place was right on the border strip; not even the GDR waterworks had blueprints. Of course, at the West German water authority, they thought I was jerking them around.

ALEXANDRA DROENER: We had a burst water pipe once a month. I'd stand there with Regina, who liked to come in heels, and we'd mop up. Regina and I basically kept the place running. But I also had a lot to learn. I was 22 and wet behind the ears. I had to go to the wholesaler, get bar supplies. Horribly boring. Warehouses full of glasses, spoons and so on. Achim taught me what you need—which glasses should have measuring lines, which shouldn't. Measures, ice cube trays, plastic cups. Doing inventory, how you calculate drinks. It takes a minute to work that stuff out. At the same time, I was dancing til morning.

JOHNNIE STIELER: I was completely out of order. I basically never slept —and yet, I was happy. If I'd had any obligations, it wouldn't have worked. It was like waging war: You have to focus 100 percent or nothing comes of it.

ALEXANDRA DROENER: Of course there were palpable differences in mentality. At first, we didn't know how to deal with each other at all. Johnnie was an outrageous character with a big mouth and a ton of enthusiasm. We spoke different languages. We Wessis [West Germans] had a kind of unconscious arrogance, and Johnnie wasn't the sort of guy who'd let himself be steamrolled by the Coca Cola thing. He really supported his people, brought in Zappa, Felsen and Arne. Some of them had been friends since childhood.

JOHNNIE STIELER: I'd known Felsen, our bouncer, since I was 14. Everyone respected him. He had no problem with the police or with the tough guys. And he had a unique gift for pedagogy. He would explain to everyone why they weren't getting in. He'd start with their clothes and justify everything on the basis of their outfits. He really educated them. There were these red-light-district types from Hamburg, for example. They turned up dressed in raver gear. Or at least what they thought was raver gear. Bandanas and that sort of thing. One of them was even packing a piece under his leather vest. And Felsen just told them, “Boys, quite honestly, you look ridiculous in those getups. Besides, with that pimped-out car over there, it's obvious where you're from, there's no point trying to hide it. Where do you think you are?” The guys listened, went back to Hamburg and showed up again the next week, this time without the gun and get-ups. And Felsen let them in, too. After that, they were regulars. They were there every weekend because they liked the place so much. Inside, they were perfectly well behaved and also tipped generously. Always with a different chick on their arm. At any other club, they'd just have been turned away. But with Felsen, it was different. And as a result, this incredible social circus evolved.

DIMITRI HEGEMANN: Tresor was like an open street project. All sorts of different people washed ashore there. You'd hang around a while and then sooner or later, you had a job.

TILMAN BREMBS: After a few months, I started cleaning up after the parties. It was good, under-the-table money. Plus you always found things. Keys, pagers, glow sticks, flashlights, water guns, even a bible. Drugs, not so much—they were consumed, after all. And money, of course. Notes of all different denominations that had fallen out of peoples' pockets. That was my tip money. The worst were the beer bottles in all the deposit boxes. It was a really dirty job. Afterwards, you were just covered in dust and grime. Since then, I can clean absolutely anything. I've been immunized. Nothing could be worse than Tresor.

REGINA BAER: Tilman really wanted to spend a night at Tresor. He cleaned. And apparently, that was his greatest fulfillment. That was all he wanted to do. You shouldn't stop people like that; it's best to just let them do their thing. Otto was another castaway. In fact, he was a medical student. He was there a couple times, and then I asked him if he wanted to work as a runner. He wasn't interested. Said he'd do everything else, just not collect bottles. So then he got “everything else” as a job.

ZAPPA [Resident DJ, Walfisch]: At the very beginning, I was the maintenance guy at Tresor. Johnnie brought me in. I installed the first toilets there. During the day, I was the maintenance guy at an elementary school. I was incredibly proud to be part of this thing. I even brought my mother to Tresor, and we danced together. Johnnie proved that with a little tenacity, you could really accomplish something. You just have to do it. For me, that's still a symbol of the reunification.

TILMAN BREMBS: I didn't clean because I liked it so much, but because it was the ticket to the whole thing. Free entry, free drinks, meeting everyone. It wasn't just a job; it was more about self-discovery. Being part of a close-knit community. During the week, we were there often. We'd crack open a beer and solder something out in the courtyard with music on in the background. It was like building our own world. Like in Pippi Longstocking. Dimitri was always telling me that someday, he'd build the Techno Tower. But then you'd also need a Techno Farm where techno chickens could run around freely. And I'd really picture it there on Leipziger Straβe with that big field. It sounded so visionary. I liked that.

Andrew Field-Pickering aka Maxmillion Dunbar. Photo by

Andrew Field-Pickering aka Maxmillion Dunbar. Photo by

Inside Tresor

Inside Tresor

Dancers at Tresor

Dancers at Tresor Detroit DJ Jeff Mills, Dimitri Hegemann, and French DJ Laurent Garnier at Tresor

Detroit DJ Jeff Mills, Dimitri Hegemann, and French DJ Laurent Garnier at Tresor

Loveparade founder Dr. Motte at Tresor

Loveparade founder Dr. Motte at Tresor

Wyatt in the '60s

Wyatt in the '60s

Body/Head: Kim Gordon and Bill Nace

Body/Head: Kim Gordon and Bill Nace

Photo by Ben Pritchard

Photo by Ben Pritchard

Photo by Rune Kongsro

Photo by Rune Kongsro Matthew Mullane

Matthew Mullane Cam Deas

Cam Deas