Photos by Hedi Slimane

Even before she injected 1990s alt-rock with the femme-fury it needed and became a bedroom-wall staple for multiple generations, Courtney Love had the origin myth of a real, if unconventional, star. Her rocky childhood with hippie parents left her abandoned and eventually in juvenile hall, where she discovered punk rock by way of Patti Smith and the Pretenders. She cruised around Dublin and Portland with poetry books; stripped in such far-off locales as Alaska and Guam; acted as a "punk rock extra" in the 1986 film Sid and Nancy. At 24, Love took out a Los Angeles newspaper ad seeking comrades influenced by Big Black, Sonic Youth, and Fleetwood Mac. Hole was born.

"I wanna affect culture in a very large way," she said in the early 90s. "If I fuckin' die without having written two, three, or four brilliant rock songs, fuckin' I don't know why I lived." (See: "Doll Parts", "Miss World", "Violet", "Pretty on the Inside".) Twenty volatile years of ambition, contradiction, and loss later, Hole's definitive 1994 record Live Through This is immortal.

With its anthems tackling eating disorders, rape, and indie elitism, Live Through This bulldozed down all manner of female archetype. The record has now entered its oral-history period—and a reunion of the mid-90s Hole lineup, with drummer Patty Schemel, bassist Melissa Auf der Maur, and original guitarist Eric Erlandson, is highly likely. But revisiting this album feels especially purposeful given the devastating conditions of its release: Live Through This came out the same week that Kurt Cobain took his life, and, just two months later, Hole bassist Kristen Pfaff died of a heroin overdose. Those of us who were too young to fully grasp that in real time (I was only 4) have had the privilege of experiencing these songs with less baggage and considering them for what they are: raw, poetic, undeniable. When I played the record on a recent Saturday night, a friend unfamiliar with Hole summed it up: "This sounds like it came out today."

After spending years in New York, Love is newly settled in L.A. when I call her late last week. The smeared-lipstick alt-rock queen who once proclaimed the absurdity of "worshipping at the altar of beauty" is now entrenched in the fashion world, having done campaigns for Hedi Slimane, Versace, and Diesel. "I have always been vain in some way," Love says of her relationship to image. "All women are dichotomies, with a beautiful, sensual, passive side, and a monster, sexual, aggressive side." Her own line, called Never the Bride, is in the works, as is a memoir, which may require more time (she recently rejected a ghost-written version). Meanwhile, she is toying with the idea of a musical about Nirvana, and filming a highly opinionated YouTube series called "#COURTNEYon". Her new double A-side single, "You Know My Name" b/w "Wedding Day" is set for release this month and, while in L.A., she plans to pick up the acting career she stepped away from after her Golden Globe-nominated performance in 1996's The People vs. Larry Flynt.

As ever, conversation with Love is a roller-coaster, vastly amusing with the occasional feeling of derailed collapse. Her combustible personal life continues to serve a great foil to her wit and intelligence, and when she gets philosophical about feminism, identity, or success, it can still strike like lightning. But even Courtney Love, who turns 50 this July, can only bury the past so far—at a point, she laughs while calling herself a loner who "likes myself better on-stage than in real life." She's primarily blunt to the point of comedy, unabashedly musing on her highest-highs and lowest-lows. As her manager comes on the line to cut us off, he plainly declares, "OK kids! The party's over!" It sounds like a line he probably recycles often.

"To find your female scream and not withhold is so liberating. You can do anything then. It's like you can fly. It gives you superpowers."

Pitchfork: What have you been up to these past couple of days?

Courtney Love: I'm in my sunny rental in fabulous Beverly Hills, California, eating chocolate chip cookie dough and watching the last season of "Downton Abbey". I don't like reality shows. I have a friend in London who lets me stay at his house, a successful art dealer, and I looked at his TiVo list—he hadn't paid his cable—and it was all "The Real Housewives", and I was like, "OK, I can read a book, or I can watch 'The Real Housewives' of whatever." So I got stuck watching "The Real Housewives" of whatever. I tried all the different cities, and it was equally disgusting and awful each time. I can't believe these shows. It's terrifying. It's like, [Network screenwriter] Paddy Chayefsky was right, and here we are.

I did a video the other day, which might come out. It's typical stuff you would expect from me, directed by my friend Maximilla [Lukacs] —who does super high-femme, surreal videos—and it was total Miss Havisham. What am I wearing? A white dress! Of course! But you know what I'm not wearing? A flower crown. I have to tell you, I've never worn a flower crown, except once, in 1985, before you were born, right before Andy Warhol died. He decided I was going to be a star and put me in Interview wearing a flower crown. It was my first big piece of press. I saw pictures of Coachella and all these girls are wearing flower crowns from Urban Outfitters! Flower crowns have tipped. They might be a little bit done. Max's videos have a lot of flower crowns in them, and I said, "Max, no flower crown." For what the video cost, which was nothing, it might be good. It's not going to get 62 million hits, but it is what it is.

Pitchfork: Was there a specific reason you moved from New York back to L.A.?

CL: One was to be near [my daughter] Frances. That's the most important one. And the other is to be closer and more accessible to acting. I have a pretty big agent who's very passionate about me right now, so we're looking at film stuff. And Eric [Erlandson]'s here, so we can work on [Hole], which is a next-year, next-level concern. I'm not a theater rat, so I never got a theatrical agent [in New York] and did a play. I came really close though.

Pitchfork: What play were you going to do?

CL: I don't want to say because I might still get it. The chick won a Tony for it. It was an unknown, out-of-the-blue, very feminist—but sexual—piece. I came so close, and the producer wanted me. But the director had equity and he didn't want me. Not because of acting capacity—I was a perfect fit—but because of reputation. I really want to give a TED talk on "reputation." That is something I'm specifically equipped to discuss—how reputation can affect even your capacity to rent a place. Having good credit is irrelevant in the face of something like getting thrown out of court six years ago. I've really thought this out.

Pitchfork: Your new single "You Know My Name" references that idea.

CL: Yeah. I mean, look, it's not "Hallelujah"—I didn't write a lyric like, "I'm the little Jew that wrote the Bible." I'm not showing off the best of my lyrical capacity, but it's fucking catchy. This is a song kids are going to like a lot. I'm in the middle of writing a letter to a guy I have a crush on about this song, and how he's probably not going to like it because he's a grown-up. He's more of a Dylan type. The B-side is also fast. I think fast songs are harder to write—I set the bar really high for fast songs. We demoed 18 songs, and I threw them all out. I wanted immediate—boom—get in there, punch them in the face in under three minutes, get out!

Pitchfork: At first, I wondered why you released those songs as Courtney Love rather than as Hole, like your last album, Nobody's Daughter.

CL: Well, that was a mistake in 2010. Eric was right—I kind of cheapened the name, even though I'm legally allowed to use it. I should save "Hole" for the lineup everybody wants to see and had the balls to put Nobody's Daughter under my own name.

Pitchfork: So the Hole reunion will be happening then?

CL: I'm not going to commit to it happening, because we want an element of surprise. There's a lot of i's to be dotted and t's to be crossed. It's next year's concern, but we've hung out, we've sat down, we've met, we've jammed. There's some caveats, there's some things people need. We're older—we're all mainlining vegan food, you know what I mean? Nobody smokes other than me. No one's on drugs. Melissa drinks red wine, like me, and Patty's sober. I'd like to make sure that [my current guitarist] Micko [Larkin] stays along for that ride, because we're going to need an extra person if we do it anyway. He's been my guitarist for seven years, we have a good connection.

Pitchfork: If the mid-90s Hole lineup did reunite next year, what would playing with them again mean to you?

CL: It would only mean anything if we did something relevant. Listen, you'll love this conversation, given that you're from Pitchfork: We are the last to the dance. I saw Tom Morello the other night, and I thought Rage hadn't even [reunited], and he goes, "What are you talking about? We did a reunion from 2007 to 2011." I'm like, "Holy shit!" Then we got down to Nine Inch Nails and Soundgarden. Someone asked me to go out with Alice in Chains, and I'm like, "I can't, Layne is dead." And my manager was like, "They've had three reunions." I'm like, "That's impossible! Layne's dead!" Apparently, they had three hits on alternative radio, which there's not much of in the States—in the Nirvana glory years, there were over a thousand stations, and now there's 42.

I would say the low point of my career was in Texas, at Pizza Hut Park, opening [2010's Edgefest] at noon, first on the bill under Limp Bizkit and 30 Seconds to Mars—I didn't even put makeup on. Jared Leto is standing there with his pink mohawk after our set, and he goes, "Hey, pretty lady." And I was like, "Jared, I know you're a rock star." And he goes, "We sold out Wembley!" And I'm like, "You're Jordan Catalano... I'm sorry. I can't stick around to see you play." My daughter isn't a fan. I go by what my kid says. Her boyfriend [Isaiah Silva]—my son-in-law—has an amazing band called the Eeries. It's Oasis-tinged, but so good.

Pitchfork: What would make the Hole reunion relevant?

CL: If we can get two killer songs together and then look at an album. We definitely would be looking at an album. I can't live on the oldies circuit. The band started talking about everyone who's done it. Patty brought up that Jesus Lizard had done it, and I'm like, "Wait, wait, wait—Jesus Lizard did a reunion tour?!" Then Melissa's like, "Yeah, Sunny Day Real Estate did it." And I'm like, "How did Sunny Day Real Estate do a reunion tour?" It's like anybody that ever had a Sub Pop Single of the Month did a reunion tour! I'm like, "Next you're going to tell me that the Dwarves did it." And they did! This is crazy!

I'm the last holdout on this. And the reason it's not happening this year is because I was too late to come to the conclusion that it should be done, and to find the manager we all agree on. To make it have some ass-kicking. No one's been dormant. Patty teaches drumming and drums in three indie bands. Melissa has her metal-nerd thing going on—her dream is to play Castle Donington with Dokken. Eric hasn't flipped—I jammed with him, he's still doing his Thurston-crazy tunings, still corresponding with Kevin Shields. We all get along great. There are bands who reunite and hate each others' guts.

Pitchfork: It does seem like everyone from Hole has been busy: I saw Patty's band Upset earlier this year, and I was at Melissa's venue Basilica Hudson in upstate New York last year, and I read Eric's book a couple of years ago.

CL: Melissa's a real avid Pitchfork reader. Patty knows every single thing that's still going on with Drag City and Razor & Tie and every little label. Brody Dalle from Distillers was telling me how there are lots of cool little labels, which I'm not up on because I don't read Pitchfork every day. I read Jezebel a lot. I've tried to tweet you guys and kiss your ass, but the dude in Portland just doesn't like me. So I'm like, "OK, fine."

Pitchfork: Portland?

CL: Isn't it based in Portland?

Pitchfork: No, we're in Brooklyn and Chicago.

CL: Oh! I see, I see. I mixed it up with "Portlandia".

"The low point of my career was in Texas, at Pizza Hut Park, opening [2010's Edgefest] at noon, first on the bill under Limp Bizkit and

30 Seconds to Mars—I didn't even put makeup on."

Pitchfork: You were recently at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction on behalf of Kurt, and you spoke with Dave Grohl and Krist Novoselic for the first time in 20 years. How was that?

CL: It was such a good night. I'm sad Frances was sick—she had a 102-degree fever, but then went to Coachella three days later? I was like, "What are you doing?" I went over and put eucalyptus candles out and rubbed her little chest. She really missed out on a heavy night.

To us, back in the day, the Rock Hall was cheesy. It's a place where Eric Clapton has been inducted three times. But somewhere in the aughts, Patti Smith demanded to be in, and then R.E.M. got in—either we all grew older, or it became cooler. The E Street Band definitely took over 80 minutes for their induction. [laughs] Unfortunately, there was my slip of the tongue ["My Springsteen problem is just that saxophones don't belong in rock'n'roll"], which was just a stupid thing blown way out of context. I had to write apology letters. I can't go pissing off big rock stars who I like, who are nice to me. But listen to [X-Ray Spex's] Germfree Adolescents—accidents are great in rock'n'roll, sometimes.

Pitchfork: Did you talk to Grohl and Novoselic?

CL: We did. On my way to the bathroom, I saw Grohl, and Grohl saw me, and he came up to me first—which really pissed me off, because I was going to go up to him first. [laughs] I wanted to beat him to the punch. I was like, "All right, no matter what happens, we're not going to be bitches." That was my attitude going in, and obviously his. Not much else needs to be said. We just both knew it was time to let it go, and we were ready to do it.

It's been 20 years—we didn't even talk at the funeral. None of us. And so, 20 years of me getting Yoko-bashed, and Dave bashing, and me bashing and making it worse, all that shit. The legal stuff, the trial. We just buried it. It was really deep. It brings tears to my eyes to even talk about it. There were certain lawyers who called me tearfully and said it was the most moving moment of the night. There were some hecklers who booed me, which was weird and off and scary. I ignored it. I just looked at who was on stage and was like, "Ah, fuck it."

Pitchfork: Did it make sense to you that Lorde and St. Vincent were there singing in Nirvana?

CL: Not at first. Initially, I thought it was sexist, and a little bit ghettoizing. But then I was like, "No, Kurt would have loved this." And there's reality to it. Apparently, no high profile dudes wanted to do it. It's interesting, isn't it? I mean, I don't know where Lorde is going. I like the St. Vincent girl a lot—I looked at some of her YouTubes and I like her look, her attitude, her whole thing. She was pretty cool, especially for being as nervous as she probably was. But I am telling you—the Kim Gordon moment was so punk. Kim gave the punkest performance, the one that Kurt would've approved of the most. It was the punkest thing the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame has ever seen. I was really proud of that.

She came out wearing a striped mini-dress and did this total panty-roll on the floor. She rocked it. It was totally flat. I swear to god, I was watching [Rolling Stone and Rock Hall founder] Jann Wenner's table, and their jaws were on the floor, because everything had been so in-tune all night. [laughs] It was truly a celebration of the spirit of what was subversive about In Utero and [Steve] Albini, and what remains punk about Nirvana. Me and Kim, we're not BFFs, but I was getting my hair done recently, and my hairdresser said, "Kim Gordon was asking how you were, she said to tell you hi." I was like, "Really? We don't really talk, but tell her hi." So we've kind of made peace through our hairdresser.

I went to the afterparty and, at that point, I was emotionally drained. There were people in the room who have stolen vast amounts of money from me. I couldn't have given a shit; I just let it go. Grohl said something good while skirting around the issue of us slamming each other for 20 years: It was just our way of dealing with the carnage we had to deal with. Someone suggested we go into the press room and hug it out, but I was like, "What? Nooo." We hugged privately. We didn't whore it out. It was genuine. I had this long speech, which I worked my ass off on, and then I saw it on the teleprompter, and was just like, "Don't even bother, just get this over with and bury the hatchet." It wasn't going to make great television, in terms of oration. I'm not getting a TED Talk because of a Hall of Fame speech, trust me.

"Kim Gordon gave the performance that Kurt would've

approved of the most. It was the punkest thing the

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame has ever seen."

Pitchfork: It's cool to hear you still screaming on your new single—does that feel as good to you now as it did 25 years ago, when you started Hole?

CL: Of course! I've never worked with Sky [Ferreira], but I've talked to her, and I'm just like, "You gotta scream more, man." Just find it. Find your scream! Even if you don't release it, find a scream. It's so liberating. You can do anything then. It's like you can fly. It gives you superpowers, to find your female scream and not withhold. It's not specifically Sky—just, anyone. I took Starred on tour, and told the singer, Liza, "You've got to scream in pitch." It makes you feel really good. It releases endorphins, oxytocin, dopamine, antidepressants. I wake up in the morning and I'm a fairly happy camper, and I don't get that depressed, but I had the worst experience playing live while I was on normal antidepressants for a very brief period. I was onstage and I couldn't connect with anything, or anybody, or with the music. Nothing reached me. I was like, "These fucking antidepressants…"

I've worked with girls who I've tried to mentor. There's this rapper, Brooke Candy, and I'm on one of her songs. We hung out in Venice. I got a guitar out, and I was like, "OK, but scream." She's got a great little-girl pop voice, too. She's pretty subversive. She's a rapper now, but I think she'll end up singing. Sia is writing her songs. She's going to blow up in that way that they blow up. She has a major label throwing boatloads of money at her—a really intense, good Steven Klein video—but she's dark and twisted. So obviously, I liked her.

I was given this "Vinyl Suite" hotel room [in Venice], and we hung out there. Carly Simon's Greatest Hits was in there, [David Bowie's] Pin Ups, Marvin Gaye's Duets, and that was about it. There was this really good stereo, and I thought, "God, I want to start collecting vinyl again." I have Kurt's vinyl, but I put it in storage, because it's so precious. I don't want to sell it ever. It's such a weird collection. Pitchfork would love it.

Pitchfork: What's it like?

CL: This collection starts at age six and ends at age 27—it's like his soul in vinyl. Yes, there’s AC/DC, some Black Sabbath, the expected stuff. But it’s mostly novelty records like Dr. Demento, and true indie of that period. Maybe we can eventually make an app out of it. Those records are somewhere in London. I felt like Kurt's vinyl was so valuable that I would either start giving them away as gifts, or donate them to be sold for charity. The woman at Christie's said, "Oh, [the collection is] worth 60,000 pounds," and just to prove her wrong, I sold one record for charity, for Mariska Hargitay's rape kit foundation, and it sold for $135,000. It was Talking Heads—I don't think that ruined the collection. I don't know what it was doing in the collection, but I do vaguely remember a Talking Heads argument.

I also gave one record to [actor] Michael Pitt, who came over to my house to find me. I guess he had done a movie [2005's Last Days] with Gus Van Sant, where he acts like he's Kurt or something. I've never seen it. There were four copies of the record, it was a 7" on Kill Rock Stars. It was one of [Kurt's ex-girlfriend and Bikini Kill drummer] Tobi [Vail]'s bands. What were they called, OK Go or something?

Pitchfork: The Go Team?

CL: I gave him the Go Team record, but I didn't give him the one with Kurt's writing all over it. Do you think Michael Pitt understands the context of what that record is at all? I tend to give things away. I give my clothes away. It's not smart.

Pitchfork: Well, you're Buddhist, right? It's in your nature to let go of things.

CL: No, no. That has nothing to do with my religion. When my mother was trying to teach me how to make friends when I was a kid, she'd bring girls over to the house and I'd give them all my clothes. Nothing changes, I still do it. And then I wonder, "Where is that really nice Isabel Marant dress that I spent a fortune on? Oh my god, I gave it to Liza."

"If I were a little girl growing up right now,

there's a lot I would be angry about."

Pitchfork: I was reading the oral history of Live Through This that was recently published on SPIN and...

CL: I didn't read it.

Pitchfork: There's a moment when you're reflecting on why the album has become iconic, and you said that maybe it's because girls don't make angry records as often as they did in the '90s. This made me think of all the places girls could possibly be drawing anger from. Where do you draw anger from now?

CL: There's not a lot of people expressing anger in the culture. They're expressing a lot of hyper-exaggerated sexuality. Like I said, I don't watch reality TV much, but sometimes I'll be on the E! channel and see that show "Total Divas", about female wrestlers. It's like, fake tits are de rigueur. Nose jobs are de rigueur. Exaggerated asses are de rigueur. Twerking is de rigueur. If I were a little girl growing up right now, there's a lot I would be angry about. I have a daughter who's got some reasons to be pissed at the world. Frances is an indie-alternative person. Her favorite band was Dresden Dolls; she's really into Amanda [Palmer]. I respect it, but I don't get it. Anyway, there's a lot I would be angry about, just, uncertainty... the 90s was a better decade, the Clinton-era. How old are you?

Pitchfork: I'm 24.

CL: Oh god. You don't even know what the 90s were like. It was a better decade in terms of punk rock. There's still good music being made, I'm just not aware of it all. Matt Koshak from Starred made me this great playlist with what's new and cool. There was some good stuff on there, like this band Wolf Eyes, or something. Is that right?

Pitchfork: They're great.

CL: I should be able to have a fluid conversation about new music, but I forgot most of the stuff on that playlist. Because there weren't a lot of chicks! If I see a chick playing guitar, I'm drawn to that band immediately. I want to know everything, even if it's completely electronic. But you have to really get my attention if you're male. I can't help it. It's part of my nature.

"I think commercial success is really important—it means you're affecting the zeitgeist. If only a hundred people know

you exist, it's harder to get your message across."

Pitchfork: There's a band called White Lung, and the singer Mish Way references you often, and one of my friends did an art exhibit last year called "Are You There Courtney? It's Me Margaret".

CL: Really?

Pitchfork: In what way would you hope these younger female artists are inspired by your music and personality?

CL: I'd hope they achieve some sort of mainstream success, so people start picking up instruments again. Because there is a reward for it. The beauty of the Nirvana moment was that it was a band succeeding on their own terms. The White Stripes have done really well on their own terms, and Jack White hasn't had to make a note out of place. I was inspired seeing Queens of the Stone Age had a #1 record in the U.S. I think commercial success is really important. It means there are more people listening, and you're affecting the zeitgeist more. If only a hundred people know you exist, it's harder to get your message across. Mainstream success is important—that's probably anathema to an indie publication like Pitchfork, but it's what I believe having experienced it personally.

There's something to be said for being PJ Harvey, too, where you can have a consistent cult following that stays with you, and you can do whatever you want. But early PJ Harvey is still what inspires me and makes me know I'm not there yet. I always knew she was better than me, and I liked that. I like knowing that there is somebody who is a better guitar player, who had it down lyrically, and kicked my ass all over town. That moment with PJ Harvey's first five records—up to White Chalk, and then I don't understand anymore. I mean, I get it: She's on a trajectory that's "cool." But I don't understand. Where is the rock? I need the rock.

Pitchfork: There is an interview you gave in the 90s where you tell girls, "Don't date the football captain. Be the football captain!" At what point did you realize you had become a football captain, that there were more women captains?

CL: I've discreetly dated a lot of people—I once dated a billionaire, mostly because it was fun to say, "I'm dating a billionaire," but we did not have the same taste in music, and it was doomed. Still, I'm a major feminist. There's a real politic in life, where I've been in rooms where real decisions are made, and it's a lot of powerful white men. There are women in those rooms, but not as many as there should be. For a little while, I got really disillusioned.

Bust had a party for Lena Dunham and didn't invite me, and I was like, "When did I get kicked out of the feminist club?" We called up Bust and said, "You're going to sell more copies with me on the cover." And Tavi [Gevinson]'s birthday is tomorrow! She's 18, and I'm going to her party. But tonight I'm going to [Dole Food heir] Justin Murdock's birthday party. Think about that dichotomy: a Murdock birthday party, and then Tavi's. I keep social with everyone because I want to know what's going on at every level. At the same time, if I'm not alone a certain amount of time per day then I'll go nuts, because I can't write and I can't think. I can’t deal with people all the time. I like being alone. I’m a bit of a cat lady in that way.

In terms of being the football captain—that statement was definitively about how there should be a sisterhood. I've been screwed by as many women as I have by men, in terms of lawyers. But lawyers don't count. If you take lawyers out of the equation, you have a more fair playing field. There is a sisterhood now, and it functions pretty well. So you have hope.

Tillman at Avast! Recording Co. in Seattle

Tillman at Avast! Recording Co. in Seattle

Photo by Matias Corral

Photo by Matias Corral Photo by Sebastien Sighell

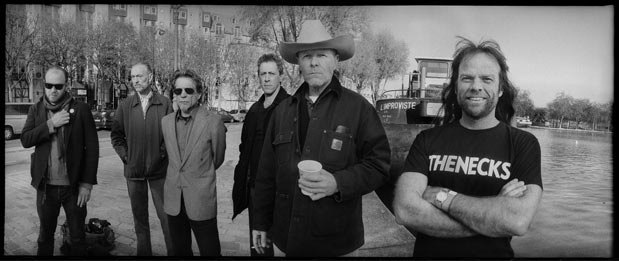

Photo by Sebastien Sighell Swans during the recording of To Be Kind at Sonic Ranch in Texas. Photo by Phil Puleo.

Swans during the recording of To Be Kind at Sonic Ranch in Texas. Photo by Phil Puleo.

Morning Routine

Morning Routine Dream Merch Item

Dream Merch Item

Bobby Sherman:

Bobby Sherman:

Photo by Dale W. Eisinger

Photo by Dale W. Eisinger

Strangest Display of Fan Affection

Strangest Display of Fan Affection

The Mohawks:

The Mohawks: