In this edition of The Out Door, we talk with father and son Yoshi and Tashi Wada about the politics of reissues and the divide between composition and improvisation, dive into the "the abyss of 78rpm record fascination" with Robert Millis of Climax Golden Twins, and explore the varying styles of solo cellists Helen Money and Julia Kent. But first, we explore the idea of "imagined communities" through the lens of a new, fascinating compilation. (Remember to follow us on Twitter for all kinds of updates on underground and experimental music.)

I: Imagined Communities

San Francisco's Lynn Fister runs micro-press and label Watery Starve Press and makes music as Aloonaluna. The latest release through the label is Taxidermy of Unicorns, a book/double cassette package that features words, art, and music by four different women. In an essay included in the collection, Fister explores the "immediate feeling of a collective consciousness" between herself and other female artists, working in very different musical forms. She clarifies that this doesn't mean she can relate to all females, or that she can't relate to males, or that any two individual experiences are ever the same. But still, as she puts it, "There's something about the female experience that feels shared, no matter how imaginary it may be."

Packaging for Taxidermy of Unicorns

Packaging for Taxidermy of Unicorns

I'm struck by that use of "imaginary." It suggests that if we admit that classifications exist only in our minds, we can discuss them without boxing people into them. And we can define and control them ourselves rather than vice versa. Fister found inspiration for this idea in Benedict Anderson's book Imagined Communities. "His idea was that all these communities are formed and imagined," she tells me, speaking on the phone from her home. "They're not real-- we create those divisions. But they have real consequences because people believe them."

"I feel that I connect to female artists not just because of gender, but that gender does help me connect-- and I don't know why," she continues. "I think it's the way people learn to interact in whatever kind of group they are classified in. Somehow a commonality develops, and I feel I can understand it even if I've never met the person."

Part of what makes Fister's perspective compelling is that she acts on these ideas through her art. Taxidermy of Unicorns is the perfect representation of her approach, filled with singular female voices expressing themselves across the boundaries of artistic media. All four participants work solo, and the release itself is highly individualistic-- Fister hand-packages each copy so that no two are exactly the same. (Mine, pictured above, came with some string, wool, and a bird feather.)

Various artists: Taxidermy of Unicorns sampler on SoundCloud.

More importantly, the work on Taxidermy of Unicorns is varied and personal. Birds of Passage (aka New Zealander Alicia Merz) offers patient music that at times seems to stand still-- yet, as Fister puts it, "it leaves so much room for the listener, [and] it makes you think about so much else." The contribution of France's Felicia Atkinson, who works as Je Suis le Petit Chevalier, bubbles and rolls in intoxicating waves. "It's really elegant and primitive at the same time," says Fister, "which is a really strange combination, and I love it." Spacious, outward-bound sounds come from Rachel Evans' Motion Sickness of Time Travel, whose prolific output continually impresses Fister. "It's never redundant," she insists. "It keeps on expanding, and it's not nostalgic, not sad, not angry... I don't know how to describe it."

The five songs that Fister herself contributes as Aloonaluna deal in drone and abstraction-- she cites the work of Inca Ore as a prime inspiration. But they also make generous use of steady beats, a rarity in this type of music. Often experimental artists seem to fear the constraints of regular rhythm, but Fister finds ways to make it sound expressively open-ended.

"I try to make beats that are adrift even though they're structured. I often will loop a beat so it's a little bit off each time [it occurs]," she explains. "The idea of repeating something over and over and making it slightly different each time has a kind of expansive truth to it. Also, I listen to a lot of drifting music, but also a lot of pop and hip-hop, so that plays into my own way of making music."

As we continue to discuss women's experiences in all those kinds of music, I suggest that talking about this is necessary to get us to a point where we don't have to talk about it anymore. "I wonder if we'll ever get to that point," Fister replies with a chuckle. My immediate thought is that she's right, and that I'm being naïve.

But later I realize that's not necessarily what she means. Perhaps she's saying that even if discussing gender solved all these issues, that would be no reason to stop. We'll still want to explore commonalities, share experiences, and acknowledge or embrace whatever imaginary community we each choose to be a part of. "Knowing how someone got to where they are is so important," she says. "I think it's good to talk about it." --Marc Masters

Watch four videos from Taxidermy of Unicorns here.

Next: Pushing the cello's limits with Helen Money and Julia Kent

II: Resonant body: Solo cellists Helen Money and Julia Kent

Left: Helen Money, photo by Travis McCoy. Right: Julia Kent, photo by Fionn Reilly

Left: Helen Money, photo by Travis McCoy. Right: Julia Kent, photo by Fionn Reilly

There are specific labels associated with music for solo guitar, piano, synthesizer, and vocals, but no such obvious home exists for solo cello music. Consider Arriving Angels and Character, respective new albums by two cellists with extensive resumes and catalogs, Los Angeles' Alison Chesley and New York's Julia Kent.

Kent offered 2011's resplendent Green and Grey through Important Records, a syndicate of the furthest reaches of the avant-garde. But the Leaf Label, a British imprint with a long history of pressing against the boundaries of indie rock with acts like Caribou and Efterklang, delivered Character. Likewise, under the name Helen Money, Chesley issued 2009's In Tune on the now-defunct experimental stable Table of the Elements. But for Arriving Angels, she's made the unlikely switch to Profound Lore, a Canadian metal label better known for six strings of tremolo rather than four strings and a bow. Despite the surroundings, both Kent and Chesley feel strangely and happily at home; taken together, they offer a compelling snapshot of the variety of sounds, processes, and approaches possible with the strings of a cello and some carefully controlled accessories.

Helen Money. Photo by Travis McCoy

Helen Money. Photo by Travis McCoy

"I don't see myself as being experimental, and Table of the Elements tilted more toward that. I don't really see myself as a metal artist," explains Chesley. "But somehow I feel like I have a really strong connection in that community. There's something about metal music that likes what I like. It's visceral, and it wears its heart on its sleeve. I feel like I'm coming from the same place."

On Arriving Angels, Chesley-- a classically trained cellist whose former rock band, Verbow, released two albums on Epic Records-- gets a little help communicating that idea from Neurosis drummer Jason Roeder. Suggested by the record's producer and Chesley's longtime friend Steve Albini, Roeder plays on several of the album's tracks. "Beautiful Friends" finds Chesley looping several passes across the cello, a long and tense melody backed by distorted swipes at the strings. She pauses, dropping suddenly into a darkened sustain that recalls the foundational drone metal of Earth. That's when Roeder makes his grand entrance, drumming a circular pattern with his tom-toms. He goads Chesley to escalate the tempo and the aggression and, ultimately, to pick a barbed rock riff from her distorted cello.

"I don't know why I like dark music, but I like music that takes me to a dark place in a good way," she says, noting that her relationship with rock music started when her brother introduced her to the Who when she was in her early 20s. Punk and indie rock soon followed, and then she joined Verbow. "I never thought I'd play it on my cello, but I ended up playing very aggressive, rhythmic parts on my cello. And that was okay with me."

Chesley originally wrote all of the drum parts Roeder plays as loops and sent them to him to see if he'd be interested in recreating them at Albini's Chicago studio, Electrical Audio. When he arrived, he ended up replacing part of the loop on "Beautiful Friends" with his own ideas. In the brooding and building "Shrapnel", Roeder's drums completely supplant Chesley's loop. That's how she prefers her collaboration: In the past, Chesley's played on records from bands such as Russian Circles, Broken Social Scene, and Bob Mould; those roles are best, she says, when there is a back and forth between the band and the guest instrumentalist. It influences not only the piece she's getting paid to record, she says, but her own music, too.

"I'm always inspired by the music that those people have worked on," Chesley says. "It gives me enthusiasm for the music I'm writing."

Indeed, Chesley serves as something of an ambassador for the cello. She enjoys the thrill and labor of working with a team in a studio to make records, though since moving to Los Angeles last year, she's done much less work as a support player. Instead, she's been writing her own music and teaching cello to children, making sure they learn their fundamentals before they chase her lead of effects pedal chains and extended techniques.

She also relishes her distinct mix of formal classical training and casual rock education, especially the flexibility it provides. When she was recording with Japanese post-rock band Mono, for instance, Takaakira Goto walked into the room of classical musicians playing the string parts and explained that he wanted them to sound as though they were a cloud drifting through the sky. Some instrumentalists rolled their eyes, Chesley remember, but her background allowed her to understand his lack of technicality.

"He's just trying to express in words what a lot of people would put into dynamics," she reckons. "But it impressed me that he cared so much about evoking an image or a feeling."

Julia Kent.; photo by Pedro Anguila

Julia Kent.; photo by Pedro Anguila

Kent is a bit more reserved with her cello, both in composition and collaboration. Kent is also classically trained, though she put the instrument down for a number of years before joining wild-eyed group Rasputina after moving to New York. Where Rasputina and Chesley sometimes push the instrument until its sound only vaguely resembles the general perception of a cello, Kent's records interweave familiar tones in novel ways, with long tones intersecting lithe melodies and loops of plucked strings adding accompaniment beneath bowed shapes.

It's telling that Kent records her music in the isolation of a cluttered spare room of her New York apartment. (Kent described that space in our 2011 interview.) From there, she's able to balance the city outside with her own environment inside, a dynamic equilibrium that has helped inspire the blend of cello, found sounds, and fields recordings that define both Green and Grey and Character. "The energy of New York City is always present in whatever I do," she toldDummy Magazine earlier this year, "even when what I am doing is attempting to block it out."

Green and Grey, as its title suggests, attempted to find a balance between nature and New York, an idea not too far removed from those of Antony Hegarty, the singer that Kent has helped back for the better part of a decade. For that record, Kent wove recordings of cicadas into a fade of gentle pizzicato cello, the babble of a hyperactive brook into agile themes. But Character is more internal, both in its motivations and its sound sources.

"Rather than using field recordings of external atmospheres, I tried to bring the walls into the music. This is a much more self-contained record," Kent explains. She recorded pedestrian events such as lighting a match or wine glasses clinking and then processed them to create intriguing new textures and rhythms within the songs. "Those turned out to be some surprisingly interesting sound sources."

The field recordings of Green and Grey often served as distant bookends or background canvases, but the added elements on Character are much more present throughout each piece. The racing melodies of "Tourbillon", for example, reflect off of distant background percussion, a simple and quick click-clack rhythm affording the strings gravity. The pings (those wine glasses, perhaps?) that flit throughout "Salute" provide a delicate bell-like effect beneath Kent's steady, solemn drones. When the piece lifts in its third minute, growing louder and brighter, those samples serve as the springboard. The record is better for the shift, with the pervasiveness of those smaller samples tying together each piece and, in turn, these elegant and intricate 10 tracks.

"With the field recordings, I was trying to introduce other sounds to what was primarily cello. And now I'm becoming much more free in my approach to doing that, to using found sound and percussion and electronics," Kent explains. "I've been listening to a lot of electronic music, and that's been inspiring in terms of the variety of sounds that are out there and possible to be create. But that's also daunting, because of the infinite possibilities." -- Grayson Currin

Next: Robert Millis on his obsession with 78s, and two new Sublime Frequencies compilations

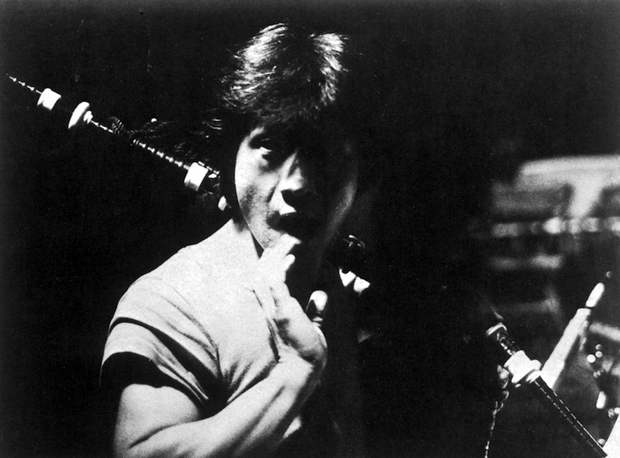

III:Robert Millis: The Spirit of 78

Robert Millis is obsessed with 78rpm records. He admits as much in the liner notes to Scattered Melodies: Korean Kayagum Sanjo, one of two collections of music from 78s that he's recently compiled for Sublime Frequencies. "Hearing this Korean music," he writes, "was the precise moment that I fell down the abyss of 78rpm record fascination that will be my doom."

The music he's referring to is known in Korea as Sanjo, an improvised style developed in the 1890s and played on a string instrument called the Kayagum. On Scattered Melodies,Millis collects Sanjo tracks from the 1920s up to the 1950s, and they're all oddly transfixing. The playing is often subdued and sparse, yet there's a fiery unpredictability to each performance. Even the softest notes leap out from under the scratchy surface noise of the 78s.

The other new 78rpm collection Millis produced, The Crying Princess, is not focused on a single style. Instead, it compiles music made in Burma as early as 1909 and as late as 1960. Heart-bursting harp-and-voice ballads sit next to piano-led pop and winding melodies crafted on electric guitar. Particularly fascinating are pieces by Po Sein, a Burmese legend whose troupes toured the country performing plays and songs, which Millis calls "the popular music of Burma before radio and TV."

Millis' interest in 78 rpm recordings and non-Western music informs his work as a researcher-- he's traveled to many countries in search of 78s-- producer, ethnographer, and musician. Alongside his other Sublime Frequencies compilations (such as Harmika Yab Yum: Folk Sounds from Nepal), he's made films in India, Southeast Asia, and Thailand. He wrote a book about 78rpm records, Victrola Favorites, for the Dust-to-Digital label. All these pursuits have influenced his own work in the long-running duo Climax Golden Twins with Jeffery Taylor (who co-authored Victrola Favorites).

Millis is currently in India on a Fulbright scholarship (pictures from his journey can be seen on his blog). He spoke to us via email about how he seeks out 78s, how time saturates their grooves, and how their sound is "the death cry of tiny insects."

"There is a beautiful mystery in these early recordings-- who were these people? How did it work? Who invented it? Why was it invented at that time?"

Pitchfork: How did you first became interested in 78rpm records?

Robert Millis: Many things one finds out about are an accident and then when the accident happens you think, "Why have I never heard this before? It is familiar, it's like coming home... and I never knew it existed until right now." When I was in high school, accidentally, somehow, in between the old Neil Young and Beatles records I was listening to, I heard a compilation of 1920s recordings by Jelly Roll Morton, and I loved them. There are some great spoken moments on those Jelly Roll records, and the sound of the human speaking voice, coming through this haze of surface noise, sounded like I was being spoken to by a spirit from the ancient past. [And] you can hear the joy they have in working together, feel the heat in the old crowded "studio" as they gathered around the single microphone.

Po Sein and Ma Kyin U: "Romantic Duet" on SoundCloud.

Years later, again accidentally, I heard the Korean music that is featured on Scattered Melodies,and it sounded like I was tuning into a radio station from 10,000 years ago or from a distant universe. Another accident: I found some Chinese Opera 78s in a junk store with beautiful labels that seemed to be whispering "buy me." There is a beautiful mystery in these early recordings--who were these people? How did it work? Who invented it? Why was it invented at that time? I have always loved music and records, loved recording, so here was the origin of that love-- how could I not help but be fascinated?

And then there is the design from that era, pre-Depression: the hand lettering, the typefaces, the illustrations. Even further, 78rpm records have an immediacy. There were no studios at that time-- barely microphones-- so there is very little in between you and the musician except shellac.

Pitchfork: How do you hunt for 78s? Do you contact people before you travel, or do you start looking once you get there?

RM: A little of both. It's nice to have a purpose when you travel, a goal. At the moment I am in India, traveling around meeting musicians and talking to collectors. In two days I am going to visit and stay with a collector who lives outside of Kochi, Kerala. He has such a thick accent I can barely understand him. I am sure the bus ride there will be confusing. He lives in the county, in the middle of the woods, in India. But he has over 30,000 78s and many old players and gramophones. I have no idea what to expect when I get there, or what to expect from getting there, but no matter what happens it will be a wild ride, and the food will be good.

"Shellac is created from the secretions of certain insects, so 78s are not vegan. That surface noise is a steel needle dragging through the effluent of millions of tiny insects. It is their death cry."

Pitchfork: You've written about your fascination with "how sounds are mediated through the equipment used to record them." How does that manifest in 78s?

RM: I have a strong interest in the resonance of objects-- literally in how sounds "sound" when played back through unusual materials or devices. Part of my interest in the 78rpm era is focused on this-- the effects of using shellac as the material from which old records are made and the surface noise this creates. Shellac is created from the secretions of certain insects, so 78s are not vegan. That surface noise is a steel needle dragging through the effluent of millions of tiny insects. It is their death cry. But perhaps I am getting carried away and the insects deserved to die for the shellac.

Also, I love how the old "talking machines" sound. They were designed to be acoustic playback devices-- electric speakers were a long way off in the future-- and so they have interesting resonances. They vibrate, they transmit sound. These early record players were extensions of the techniques of instrument building, and as someone who plays acoustic instruments I am fascinated with this.

"I am interested in the passage of time-- how time accumulates very obviously in the surface noise and wear and tear on records. And less obviously in our accumulated cultural references."

Pitchfork: What do these records say about the times in which they were made?

RM:With my 78rpm research I am not particularly interested in discographical information, or in calculating history scientifically. I am interested in the passage of time-- how time accumulates very obviously in the surface noise and wear and tear on records. And less obviously in our accumulated cultural references-- how we hear old music, nostalgia, and how newer music has appropriated (and improved or ruined) the melodies and harmonies. How imagination and hearing works. How memory works. How memory associates and layers, how we remember, why and what we remember. Music is often very colored by this, and culturally by similarities in song structures and progressions and scales. Architecturally such thoughts are easier to see: old building facades with additions, decay and damage caused by weather and time, new paint jobs on old, etc.

St. Gun Khin May: "Shan Village Part 2" on SoundCloud.

Pitchfork: Do you think it's possible to hear history in the grooves of the 78s you've compiled?

RM: It is possible, but it takes years of ninja training and specially re-constructed earlobes. Both compilations span so many years, from some of the earliest recordings made in Burma (roughly 1909) up well into the 50's. For Scattered Melodies it is perhaps more obvious, as all the tracks are essentially one solo style. Whereas The Crying Princess encompasses so many styles-- theatre, popular, Western influenced, modern. I try to point to some connections, between the Burmese harp playing and modern electric guitar for example, the connection with the Western piano. However, I don't want to be heavy handed about this-- I am no academic and frankly, this is a huge question. You have the history of two countries to contend with in the answer, not to mention the history of the recording concerns that made the recordings, not to mention the history of the music, the history of the musicians... if you want I could write a book about it. But I suggest just listening and it will be fairly obvious. Listen to the Burmese trio on side 1 of The Crying Princess. Is there anything more beautiful? Who needs context when confronted with music like that?

Pitchfork: Do you think there are any modern parallels to Po Sein and the touring troupes of Burma?

RM: Sun City Girls.

Pitchfork: Sanjo music sounds quite experimental, almost avant-garde. Do you know if it was perceived that way at the time?

RM: As far as I know it was perceived this way, though we shouldn't forget that it is not a folk music or urban music style. It was conceived as part of a tradition, as part of the existing court music of the time under royal patronage and developed by an established musician. However, it quickly grew into one of the primary musical styles of Korea. There is a slight comparison here with American blues music or even rock n' roll, which started out as outsider music, and is now more mainstream than [the] mainstream ever imagined it could be. But we shouldn't make too much of that because as I said, it developed under royal patronage as court music.

Shim Sang-Gun: "Chungchungmori" on SoundCloud.

Pitchfork: What do you find fascinating about the Sanjo style?

RM: There are several things I love about this music: it is very textural, it revels in the snaps and pops created through a very visceral style of playing, the vibrato goes on even after the tone or the musical note has died away. The string bends are very deep and exaggerated yet so precise. I love that it is in part improvisation, with shouts of encouragement from the accompanying drummer.

Pitchfork: How has your interest in these older musical forms influenced your work with Climax Golden Twins?

RM: My interest actually grew out of the work I have done in CGT. Initially I and my good friend Jeffery Taylor, with whom I founded CGT, collected 78s together. We used 78s in several CGT compositions; records were broken over each other's heads at some shows. We also cover songs from this era-- mostly American hillbilly and blues numbers. Our record from 2004, Highly Bred and Sweetly Tempered,is completely a reaction to all the music from this era we were listening to, absorbing, and collecting, especially Harry Smith's Anthology of American Folk Music. It might not sound like it, which is as it should be, but it is.

Pitchfork: How did you put together the Victrola Favorites book?

RM: It grew out of the Victrola Favoritescassette series Jeffery and I had been working on. The cassettes were loosely themed collections of 78s played on an old Victrola. After Dust-to-Digital offered us a release we began scanning labels, recording tracks, and working with a fantastic book designer named John Hubbard. It was a slow process-- improv book design, you could call it. Right from the beginning, though, it was conceived as a way to create two separate narratives: one of the imagery, the paper ephemera, the sleeves, labels, photos, etc, with the music being a separate yet connected thing unto itself. So many people expect the two to correspond, but they were never meant to. It was a celebration of the era, of our collections, of the act of collecting, of discovering new (old) music, and of design.

Pitchfork: You've designed covers for Sublime Frequencies and Dust-to-Digital. How do you go about making those?

RM: I have not designed much for Dust-to-Digital, just a few things, or things in collaborations with others (such as "…i listen to the wind that obliterates my traces" in collaboration with Hubbard and author Steve Roden). For Sublime, half the things I have designed are for my own projects. For the rest I draw inspiration from 1960s and 70s LP designs, or work with the great photos collected by the compilers themselves. I do not really consider myself a designer, though. People like John Hubbard are "real" designers. Also Jeffery Taylor has a natural design aesthetic, and of course Alan Bishop [co-founder of Sublime Frequencies] has a great visual style as well. I just learn from them and from keeping my eyes open. --Marc Masters

Next: Yoshi and Tashi Wada on EM's reissues of Yoshi's seminal drone works

IV: Sound reproduction: Yoshi and Tashi Wada

In the last five years, the whimsical and venerable Japanese label EM Records has taken up the task of asserting Yoshi Wada's role as an eminent and innovative drone pioneer through a series of reissues and archival releases. At best, this music originally had an audience of listeners lucky enough to secure original copies of his very few and very limited releases. At worst, however, this material was heard only by the handful of attendees at Wada's performances two or three decades ago.

"I was an ignored guy," Wada says, "an unknown guy."

EM has spared little expense in the effort-- each of the label's four Wada releases have resembled library books. Earth Horns With Electronic Drones captured a four-person ensemble playing the massive steel pipe "horns" Wada built in the early 1970s. Its high-powered and immersive drones came carved into three LPs, accompanied by an essay from Wada, photos depicting the horns in their monolithic glory, and a promotional poster from a subsequent 1975 concert by Wada's "Lip Vibrators", featuring fellow traveler Rhys Chatham on "20' pipe horn." At the time, Wada, an early Fluxus member, wasn't interested in releasing records, diminishing the memory of the work he'd done. These new packages represent that work and reaffirm his place in conversations about drone, minimalism and, quite simply, the sheer power of sound.

The fifth and latest such release is Singing in Unison, which captures Wada's singing trio from the late 70s delivering a series of similarly distended and enveloping vocal drones in the legendary performance space the Kitchen. These pieces were inspired by various folk traditions and the work of two Wada mentors, La Monte Young and Pandit Pran Nath.

The artwork for Singing in Unison

Somehow sinister and gorgeous, the performances presented by Unison are a testament to Wada's pursuit of sustained sound through whatever mechanism seemed most suited. Over the years, he's used not only instruments made of plumbing equipment and creaking voices but also bagpipes of his own construction, the innards of large buildings, and nautical horns to explore systems of musical sustain and decay and, mostly, the magic that happens when those properties are no longer a binary.

We spoke with Wada in San Francisco, where he has lived for more than a decade after spending the bulk of his career in New York City. He talked about his newfound legacy status, the perpetuation of his music, and the divide between composition and improvisation.

"Some of what I did in the past, I don't think people appreciated. And now, people are appreciating the body of what I have done. They feel the value of it."

Pitchfork: The release of Singing in Unison is part of a larger operation to archive many of your works that, outside of their performances, have never been heard. Why now?

Yoshi Wada: I wasn't so interested in merchandising through CD or whatever form. I wasn't really so aggressive about promoting my own work. I had my recordings from the past, but I never thought someone was interested in releasing it. But then EM Records and other people were asking, "Let's do it." I'm a laidback, lazy guy, so if somebody wants to release it, I will agree. That's how it happened in the last five or six years.

I have a DVD project. EM Records is interested in releasing some other recordings, but that's frankly not my interest right now in life. What I am interested in is the DVD form with sound installations. I am working on an archive in a way.

I do have more recordings, but I have to go through them and think about what to release. I don't want to release things too similar to each other. I've been working on selecting something different from my other work. If a piece is still valid today, I will release it.

Yoshi Wada: "March 15 - Part 1" on SoundCloud.

Pitchfork: What makes a piece valid for you two or three decades later?

YW: At the beginning, I felt sort of reluctant about my music from my past. But in the last couple of years, I felt good about what I did in the past. The way I see my work, time passes from the time I performed or recorded a work. When I look at it now, 25 years or 30 years ago, if I see that it has value today, I will agree to release it.

Some of what I did in the past, I don't think people appreciated. And now, people are appreciating the body of what I have done today. They feel the value of it.

Pitchfork: Have you been surprised by the positive reception for these releases?

YW: I'm an old guy. I'm 69. I was surprised, frankly. I was an ignored guy and have been for many years. But I suppose I became well-known after being ignored. After the release of the CDs and LPs, especially the LPs, people like it. I was impressed.

Pitchfork: Singing in Unison emerged as a synthesis of many of your interests and influences, including folk singing and the music of La Monte Young. Can you tell me how the piece came together?

YW: In the early 70s, I studied with La Monte Young, which was more like electronic music. Later on, Pandit Pran Nath came to New York. What he taught me was to be in tune and about intonation. I would sing myself with a tambura and just regular a cappella singing and practicing. I did that around 1973 and 1974, and I finally developed my own style of singing.

The turning point around that time was that I went to an Ethnic Music Expo in Queens, New York. There were Macedonian women singing. It was a small group, and they were singing in unison and in a very high pitch. It was a really piercing and traveling sound. I couldn't understand the words, but it didn't matter anyway about the meaning of the words. What impressed me was that they weren't trained musicians. Rather, they were like farmers and peasants in the region. The meaning came from everyday life.

Yoshi Wada: "March 15 - Part 2" on SoundCloud.

After I heard this singing, I organized a three-man choir. Prior to that, we had a Macedonian woman singer showing us what to sing. After that, we developed our singing in unison. It was all improvisation. It wasn't easy to synchronize because we weren't trained singers ourselves, but slowly we got into it. This was based on my own notation, but still it was improvised completely.

Pitchfork: Listening to the music, the singing presents a strange mix of feelings. It seems mournful and strangely ecstatic, too.

YW: I didn't understand the words, but I don't think it matters because it was much more a sound study. The Macedonian women singers sometimes sing farming tunes, something they have when they're working. I guess they were happy about singing and working at the same time. I wasn't working and singing, but it was a great feeling as a group activity. You're in tune with other people, singing.

Pitchfork: Similar to Macedonian singing, another of your strong interests was the drone of bagpipe music. You moved to New York after being born and going to school in Kyoto, so how did you first discover bagpipe music?

YW: I heard the bagpipes in 1976 or 1977. I went to the Scottish Games. It was outdoors, of course. It was a competition and demonstration, and the first time I heard the whole thing was such a great experience. At the time, I met a bagpiper, Nancy Crutcher. She lived in New York, and I started taking lessons. I went to weekly bagpipe sessions in a church basement in Manhattan. I wasn't interested in marching band music, but I had to focus on that. Then I got into one of the Scottish classical styles called piobaireachd, which is a very old music that started around the 1700s or something. I really got into this music. After that, I started to compose bagpipe music in my notations. Then I started building bagpipes by myself, and then I started to perform with the instrument myself in the 1980s.

Pitchfork: What appealed to you about bagpipe music?

YW: For a long time in the 1970s, I was experimenting to build musical instruments and use them. I did a lot of ethnic music studies and other things, like electronic music. Making homemade musical instruments and performing was my major activity from the time.

Scottish bagpipe has two tenors and one bass-- three drone pipes-- and then the one chanter. If you put bagpipes together, it creates such a fine sound. I had been working on the overtone series from the beginning, so it made sense to me to follow the bagpipes. I felt it was the way to go with the overtone series. I also made a brass reed instrument to go with the bagpipe, and I was also singing with it. After that period passed, I got back to playing Scottish pipes with other people.

Initially, when I was making the bagpipes and reed instruments, it was different from the other instruments. In terms of sound itself, it may not be different, but in performing with it, it was a necessity to build it if I was going to perform and make scores with it. By making the instruments, it helped me compose the way I want.

Pitchfork: You also famously built your Earth Horns, massive pipes that produced low and long notes. What inspired that?

YW: That started in the earlier 70s. I was actually in construction, doing plumbing work to earn money. One day, I picked up a pipe and blew it, and it made an interesting sound. I had to get a much larger size pipes and begin experimenting. It was an unknown thing. I ended up with gigantic pipe instruments called Earth Horns. It was a really low pitch, a very extreme range, like a sheep demon being created. It was 30 to 60 Hz.

I organized an ensemble. It was quite interesting, because nobody had that kind of idea of building such instruments. The title of the piece was Earth HornsWith Electronic Drone. Some of them I had to give up because they were so heavy-- steel pipes, after all. At one point, I couldn't carry them around anymore, so I stopped. The Emily Harvey Foundation in New York has a couple of the instruments, and I have a couple of them in San Francisco, too. In 2009, I did perform at the Emily Harvey Foundation with the Earth Horns.

Pitchfork: With many of your pieces, there is a slight line between composition and improvisation, if any. There seem to be parameters for what will happen during a piece, but the terms of the performance itself seem very fluid. How do you distinguish composition from improvisations?

YW: I don't think I differentiate between composition and improvisation. Improvisation could be a large part of a composition. To me, even for La Monte Young himself, improvisation is composition. It's different from the earlier pieces, but I do think most of his music is improvisation. Most of my music is improvisation, and composition is improvisation. Even if I have a score, it is improvisation. Now that I'm thinking about it, I made score for Off the Wall. I had notation, but improvisation is part of it.

Pitchfork: You've lately been making music with your son, Tashi. Did you ever expect that this music you make would become a part of your family?

YW: At the beginning, I didn't know he was going to do the things I do. He wasn't doing it! It's been about three or four years. He knows much more in musical terms, and he was helping me three or four years ago. We can communicate well, and it's easy for us to perform together. He himself is a very good composer.

In 2010, Tashi Wada released Alignment, a stunning debut that used bowed strings to create waves of microtonal phosphorescence. Wada followed that release last year with Gradient, a similar study that proved that his music is not far removed from the orbit of his father's cohorts in the early 70s. We spoke with Wada about the influence his father has had on his own music and its place in the world.

Pitchfork: When did you first begin to understand the sort of music your father makes?

Tashi Wada: My early associations with my dad's work aren't specifically music-related. I suppose his work had a way of blending in with our family's life in New York City: his loft on Mercer St where we lived, his studio/workshop in the basement, the variety of artists in the building and SoHo in general, Fluxus, his jobs in construction, etc.

But I knew he was up to something. I remember, in elementary school, being asked what my father does and not knowing how to answer. When I asked my mom what I should say next time, she replied, "Just say he's self-employed." I love that.

I began to make sense of what he was doing, and how it fit into the world, as a teenager after we moved to California. Eventually, I ended up going to school at the California Institute of the Arts to study with James Tenney, who happened to be an old friend of Yoshi's. Everything really started to come full circle.

Pitchfork: When did you first perform with your father?

TW: The first time my dad and I performed together was in 2009 at the Emily Harvey Foundation in New York City. Taketo Shimada asked Yoshi to put together a performance of his piece Earth Horns With Electronic Drone after seeing some of the instruments in Emily Harvey's collection. Yoshi no longer had the electronic drone system, so I played the part on reed organ and sine waves. Since then, we've performed together a handful of times. We like to joke it's a family business, but there's no money.

Pitchfork: Many of your father's pieces were specific to the moment and the setting, which make them strange fits for physical media. Do you think the sound-only aspect of a CD or LP diminishes the experience of his music, or is it more important that these records exist for listening, buying and understanding?

TW: I associate Yoshi's music with building and sculpture. He trained as a sculptor in college. Each of the sounds is specific to the thing making it. It has to do with physical presence.

The recordings tend to highlight more of the compositional aspects of his pieces, how things are structured, etc. I approach Yoshi's CD and LP releases primarily as a form of documentation. Most of the recordings weren't made with the intention of releasing them. They aren't the work itself, but they give you an idea of what the work is like.

That's why Yoshi, Koki Emura of EM Records and I have made an effort to include things like photos, scores and notes. We're currently sorting through videos of Yoshi's installations to have them transferred for some kind of release.

Pitchfork: What influence has his music had on your own music?

TW: When I was just getting started making my own music, my dad said, "You should think about art, but also anti-art and non-art."

It's difficult for me to single out the ways my dad and his work have influenced me. There's an unusual emotional quality to his music, which I understand. It isn't so obvious; it's very personal. --Grayson Currin