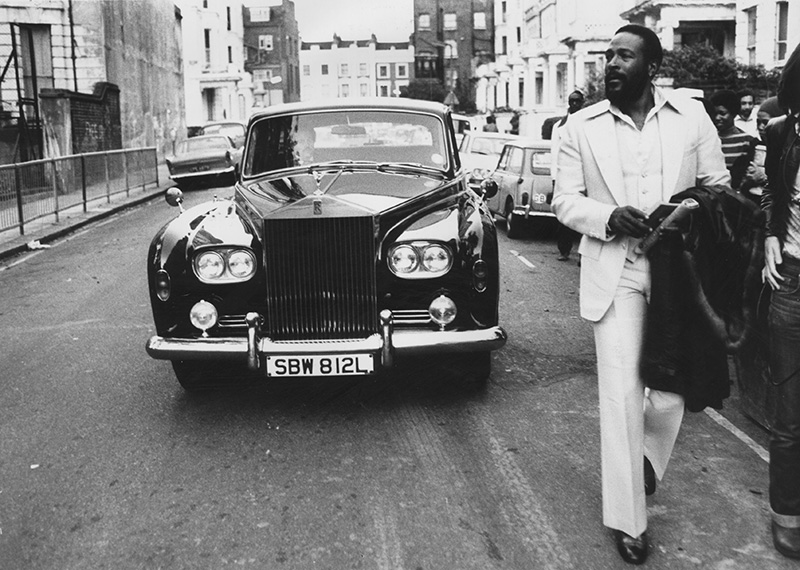

Marvin Gaye’s I Want You was originally released 40 years ago this month, and the timing feels somewhat fitting given today’s essential dialogue about the existential value of black life. You can’t make a convincing argument that black lives matter if you’re not also willing to acknowledge that black sexuality, romance, and love—aspects that have been historically threatened, circumscribed, and limited by the horrors of slavery and legally enforced systems of segregation and brutality—matter too. So as we join in the #blacklivesmatter fight, we would do well to recall that #blackerotics have always been an indispensable tool of community recalcitrance and survival.

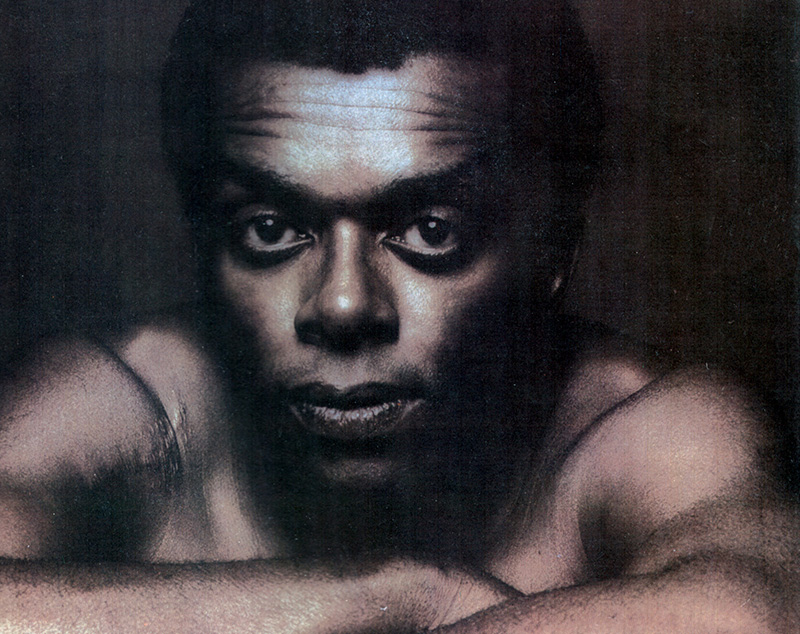

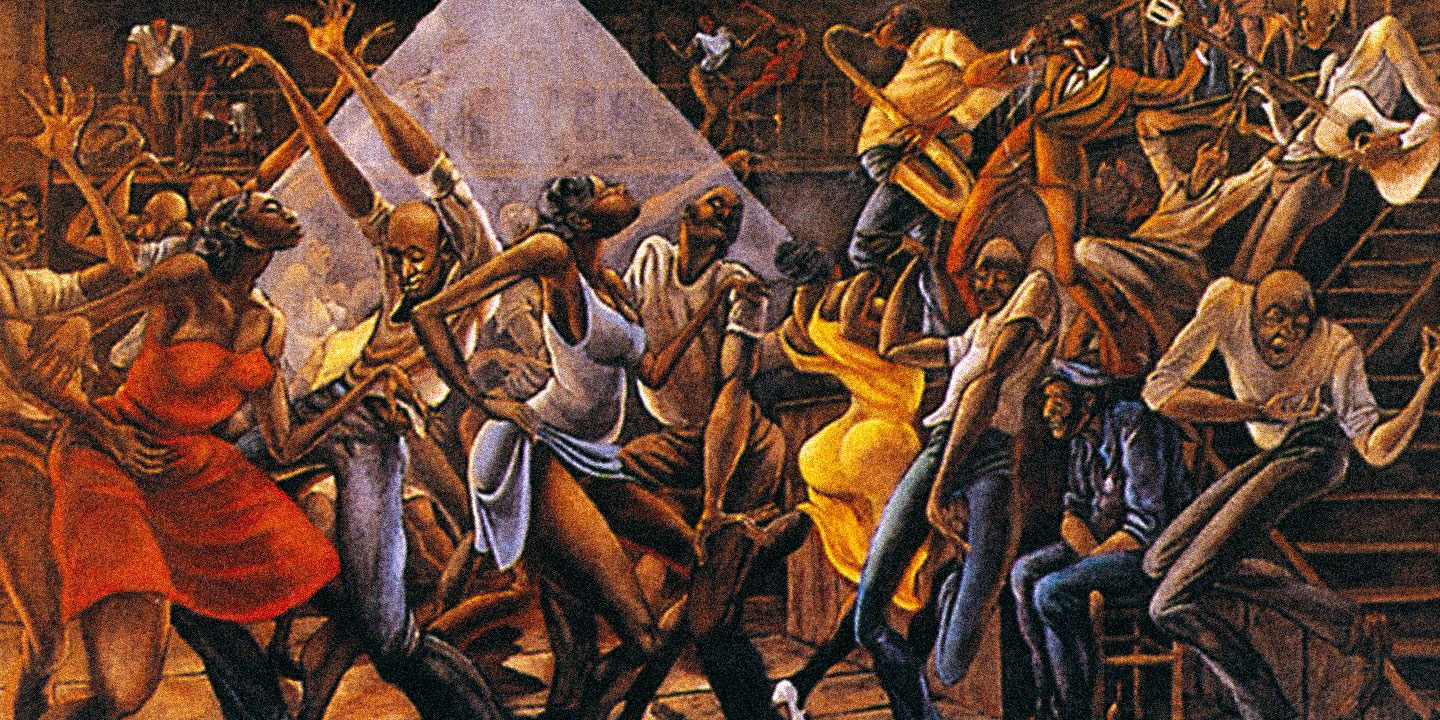

Like no other record before or since, I Want You captures the distilled feeling and aesthetics of black sensuality, sex, and simmering erotic desire—right down to the seductive bump ‘n’ grind cover art by the late great Ernie Barnes. With its ambient soundscapes, yearning melodies, experimental tempos, elegant chord changes, and haunting lyrics, the album is, for my money, the sexiest rhythm and blues record ever made. Sure, pheromone-inducing records like Sade’s Diamond Life, Maxwell’s Embrya, and D’Angelo’s Voodoo are worthy contenders to that throne—but all those albums were directly influenced by I Want You’s languid flow. Anchored by melancholic tracks like “After the Dance” and “Come Live with Me Angel,” I Want You is a gorgeous and delicate ballet of adult romantic desire, featuring a Latin-influenced early-disco-meets-slow-jam sound that remains a staple of Quiet Storm radio playlists everywhere.

Gaye hardly scaled this sensual avant-garde pinnacle by himself: I Want You’s artistic success had everything to do with the outsize genius of the album’s co-songwriter and producer Leon Ware, an underappreciated R&B journeyman. In 2009, when I was the Artistic Director of New York University’s Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music, I curated a series of events to celebrate Motown’s 50th anniversary and asked Ware to fly into New York to spend a week in residence at the school. He gracefully obliged. As part of his brief tenure, he appeared at a special event at the Audio Engineering Society (AES) convention, where he spoke about the making of I Want You. With my colleague Harry Weinger, Grammy-winning reissue producer and Vice President of A&R at Universal Music Enterprises, sitting in as co-moderator, the three of us chatted about the album’s genesis, the difference between sex and making love, Gaye’s unique recording process, and more. Thanks to the generosity of AES, we’re reprinting an edited version of that 90-minute interview; outside of the AES convention room in which it happened, this conversation has never surfaced in print before. I hope publishing it here adds to our collective appreciation of an unparalleled model of musicalized sensuality.

"People like me and Marvin were bringing to the forefront a love that is natural. It is not prefabricated. It is not nasty. That’s why I can tell my granddaughter [about this music] without being ashamed and having her think that her grandfather is a dirty old man."

—I Want You producer Leon Ware

Jason King: By the time I Want You was released in 1976, it had been three years since Marvin's last studio album, Let's Get It On. How did you get involved in the project?

Leon Ware: Marvin was on a religious sabbatical. He had sworn off ever doing another commercial record again. Berry Gordy changed his mind. It started with my co-writer of [the early Michael Jackson hit] "I Wanna Be Where You Are," which was Diana Ross' brother "T-Boy"—we were doing a demo of some songs to get him an album deal. And in the process I had a song called "I Want You" that I wrote completely myself and put on the demo. Berry came into the studio as we were doing the demo for "T-Boy" and heard this song, got very excited, and took it to Marvin, who fell in love with it.

When we finished the "I Want You" single, I was at Marvin's house late one night, and he was in a room listening to some music, and I was in another room playing a record that was never really released that had three duets I did with Minnie Riperton. Marvin heard it through the wall and came into the room and asked, “What's that you're playing?” We listened to it three times, and as the sun was coming up, Marvin walked towards his bedroom, turned around, looked at me, and said, “If you give me that album, I'll do the whole thing.” I said, “That's a good idea, but Berry will never go for it.” In Motown's history, there had been only a few albums with one producer and one writer who did everything. But I kept thinking to myself, Wow, this would be great if it came out.

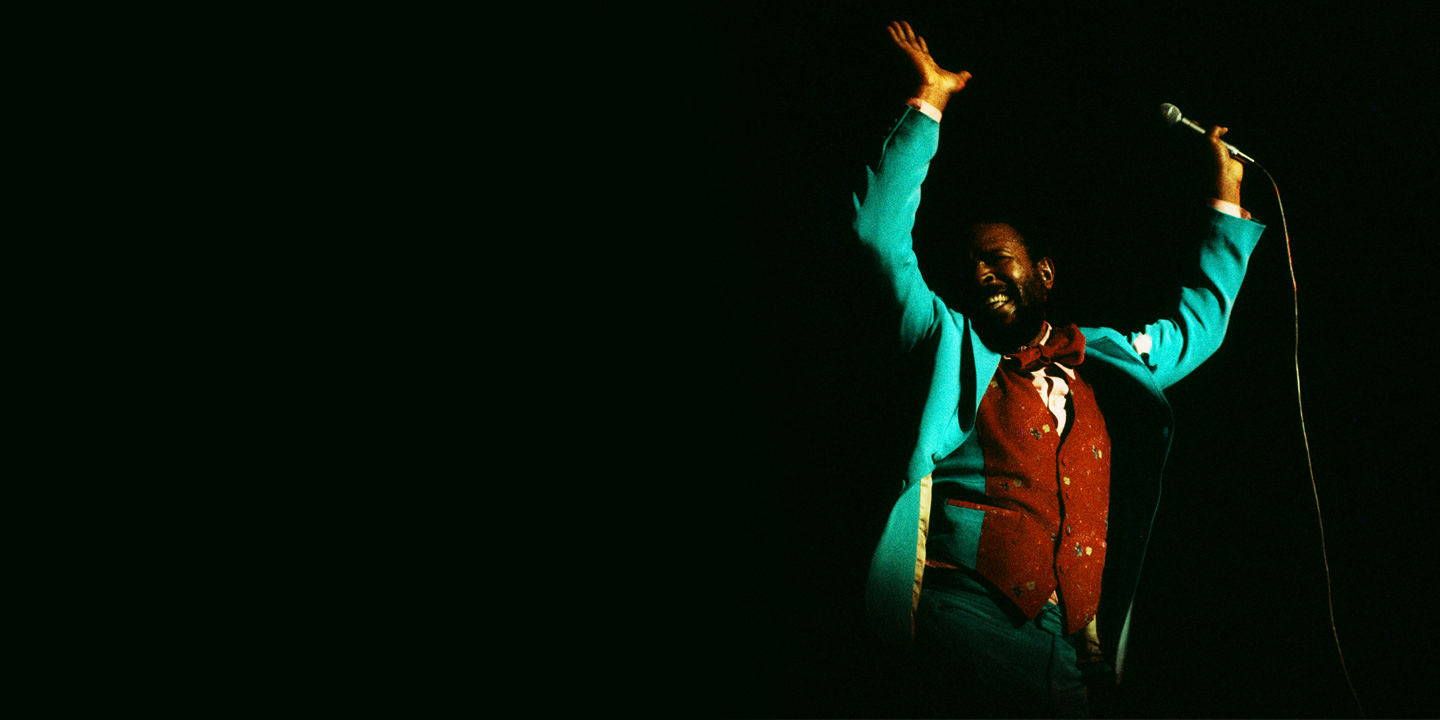

Motown was known for quality control—the world could use a little bit of that right now—and when we played them the album at a meeting after we finished it, the room was so quiet. Berry stood up and turned around to the 30 people there, looking for me. He said, “Leon, I don't know how you did this.” Everybody knew what he was talking about. I did too. I turned to Berry and said, “Look, it wasn't me.” I brought the music, but the magic that Marvin brought with his vocals made it a classic; I had a body, but Marvin and me dressed it together. Being two men sincerely dedicated to sensuality, that was all we ever discussed. All that happened on that project was so innate, so natural. It deserves to be timeless. The aroma that anybody gets from it is real, and you should be feeling it.

JK: Where was Marvin at mentally while making this record? Is it right that his second wife, Janis Hunter, is the subject of the album?

LW: Very much so. The time when we did I Want You had to be the most happy time in Marvin's life, because he was freshly in love, and the album exhibits that atmosphere. When I'm told by different people all over the world how many babies that album has made—the record stands so high in my life. I could not be a prouder man.

Harry Weinger: Did you direct Marvin in any of the album’s vocals or did he really do them all himself?

LW: He did them all himself. I would be singing something or he would sing something, and it would be like we were telepathically communicating—it was the most effortless collaboration I've ever had. It was uncanny how we would wind up with the same thing. For “I Want You,” Marvin did the background, the lead, and the ad lib in one night. It’s three songs in one. That's all Marvin Gaye. He was a genius when it came to backgrounds, what he did with rhythms, and how he would use his voice like an instrument. He was a purist who wouldn't let a phrase or a riff go until he loved it. He would wear you out. Because everything Marvin sung was right to the studio, and he would say, “I could do that better.” And we would say, “Marvin, please don't touch that, because we don't have anymore tracks.”

Marvin is also the only man I have ever seen lay down and sing. I first saw that happen when he was singing a part of "After the Dance." I walked into the studio and could hear his voice, but he wasn’t in the vocal booth. I looked at [engineer] Art Stewart and said, “Where is he at?” Art said, “Right there.” And there was Marvin, with one hand with one thing—I won't tell you what it was, you can imagine—and the other hand with a mic. Believe me, I’ve tried to sing laying down, it's almost impossible. Marvin was singing as though he was on his feet, with as full delivery as possible, but he was as relaxed as I've ever seen anybody.

HW: One of the production details we should note is that Motown had a studio in Los Angeles, but Marvin built his own studio as a real flag for independence—that's why there was no clock. There was a guest room upstairs, and he could go there and take a nap. He really had autonomy.

LW: Out of the 13 months we took to make the album, there was six months of partying. Seriously. We would come into the studio, and Marvin would say, “Let's go play basketball.” And we would play basketball half the day, on studio time. There was no pressure.

I Want You is a testament to people just getting together and doing something. One of the most important things to me, from a professional point of view, is the fact that we could do a project like this and never ever ever speak about percentages; in my whole life in the music business, that was the only collaboration where we never approached “who did what?” or whatever. And it turned out to be my most appreciated work, the nucleus of my life as a producer. When people are working together, especially now, [percentages] are the first thing that's talked about, even before they make the record. And that clouds the issue, which is to write a piece of work that you and the world will love. Me and Marvin understood that a song is not a percentage, and it's important for people in the business to realize the percentage you want is 100 percent acceptance from the world, no matter how many people it takes to do it.

JK: The record was controversial for critics in a lot of ways, because whereas What’s Going On had Marvin using his overlapping voices to offer a prescription for the social ills of the time, he was doing the same thing for the bedroom here.

LW: There’s a very intentional allure; the young artists of today who approach the idea of being sensual have forgotten that there's a process called foreplay which plays a large part of making love. In our approach, me and Marvin were very respectful to the women that we love in our life, and having that respect makes you wanna say and do things that make the final—if you wanna say—climax.

JK: I actually found a review of I Want You from 1976 that read: “I must confess, I’m not a fan on Marvin Gaye. His music has always struck me as being horny without any musical or artistic talent. So… it’s safe to say that there are at least three utilitarian purposes of this horny Marvin Gaye record: You can dance to it, masturbate, or make love to it.” Part of that is a misunderstanding of black erotics and what slow jams are about: the relationship between the sensual and the spiritual and the political, and how being human is to acknowledge the sensual as part of who we are.

LW: I am now an ordained minister, and my ministry is about sensuality, because I feel the first religion should have been sensuality out of the fact that that is how everybody exists. That is what keeps the human race alive. People like me, Marvin, Barry White, Isaac Hayes—voices of the black community that brought to its public an allure that could have been called pornographic—were bringing to the forefront a love that is natural. It is not prefabricated. It is not nasty. It is not wrong to say things that make one want to make love. That’s why I can tell my granddaughter [about this music] without being ashamed and having her think that her grandfather is a dirty old man. I am proud to sit before any group and say, “Embrace where you come from, it’s not a bad place.”

The only thing I will definitely not be a party to is anything that is superficial. I’ve been asked on a couple of occasions to do soundtracks to certain movies that were pornographic. No. I love seeing people make love—not just sex. Because sex is fun, but if you’re using what God gave you, you’re cheapening that spirit. Some could say, “Sorry Leon, let’s cheapen it a little bit.” But for me, the way we are here on this planet is by way of sensuality. That’s the wonderful thing about black music and black artists from me and Marvin to many others—we made it our business and our life to say things that were intent to put people in the bedroom, or wherever the moment struck.

Music is the binding source of humanity. Without music, man would not be here. We would have already destroyed each other. And I’m glad I’m a music person. I like making the music world a richer place, because we need some more love.

JK: Some people also criticized the album for being “samey”—as far as the rhythms and tempos being similar throughout—but wasn’t that part of the point?

LW: It was totally intentional. Though some may have called it “samey,” we were lovers of another word: “concept.” The concept is to take a listener on a ride through the last song; all the songs are connected but each one gives you a different attitude or feeling. I come from a world of writers and producers that believe that you’re supposed to learn from each piece and never ever repeat yourself. I have a history of being in the business for nearly 40 years, and I don’t know how many hits I have, but it’s enough for me to know that you cannot sing one of my songs over the other. Me and Marvin practiced that throughout the whole album; we didn’t want the songs to sound the same. The whole beauty of that particular album was a testament to what a concept means.

JK: Let’s talk about the arranging of the record, because it's so complex and extremely sophisticated, especially on a track like "Since I Had You."

LW: Well, I'll tell you a funny story about that song. The original was written by me and Pam Sawyer, and when Marvin was doing the song, he walked into the studio and pulled me to the side and said, "I like the melody, but do you mind if I change the lyric?" I said, “No, what do you feel?" So we went back in the studio and he started singing. Then Pam arrived when Marvin was halfway through the song and she had this look on her face—being white, she got flush. So I’m standing there looking at her and thinking, What’s wrong? There were about 12 of us in the studio, and we were all totally elated. So she pulls me out to the side and says, “That’s not my lyric.” I said “But Pam, it’s Marvin.” And she said, “I don’t care. My lyric’s not being sung.” And I said, “Pam, you have to understand, if I go out there and tell Marvin that you don’t like what he’s singing…” Marvin had a known reputation—if you said anything in the process of him singing, he didn’t argue, he just left the studio. You’d be looking for him. So I told her, “You’ll have to tell Marvin yourself.” She left. She never said anything about it. Then the song came out. Me and Pam laugh about it from time to time; we came to an understanding after it was done, because she happened to fall in love with it.

As far as the arrangements, I was blessed with some really talented arrangers; there are two songs that I gave the arranger some string lines, but 95 percent of the strings and horns were done by the arrangers. Coleridge Taylor Perkinson was the arranger who brought several people to their knees when we heard the strings on “I Want You.” When people hear something that they love, they close their eyes—and I saw a lot of eyes closed during that session. There were three different arrangers on the whole album: Coleridge Taylor Perkinson, David Blumberg, and Paul Riser.

I love giving people their just due, and that’s one thing a lot of young people today should get into. People are called what they are because they go to school and deserve these titles that they get. In today’s world, something about that doesn’t exist; we give people titles but they have not done the homework to deserve them. It’s important because if you don’t do something well yourself, there are people that do do it well. From Ellington to Gershwin to all of the records that you look back on as well-constructed compositions, there were a lot of professionals involved. They were specialists: the singer, the producer, the arranger, the engineer—all of them were separate people who joined together and did a process. They weren’t just beginners. Professionals working together come up with work that can wind up being timeless. I’m only making a point of it because, in looking at records of the past 15 years, there are really talented people making those records, but they’re forgetting something. Combining your talent with other really talented people isn’t a waste.