LUH: "I&I" (via SoundCloud)

The origin story of Ellery James Roberts and Ebony Hoorn’s romantic and artistic partnership is too bloody to be a meet-cute. They first crossed paths in October 2012 at a party in the sketchy part of Manchester, where Roberts was living at the time. As Hoorn tells it: “I was just sitting in the kitchen watching a movie and Ellery came in, having just cut his wrist.” Roberts laughs. “Not on purpose,” he clarifies.

Turns out Roberts had just taken part in a fight that involved the other guy smashing a wine bottle across his arm. “It gave me a nice scar there that was a bit of a mess for a while,” Roberts says. It also led to him running into Hoorn, a Dutch artist with a background in photography and film, and starting a new project with her called LUH. Best known as the impossibly craggy voice behind short-lived indie rockers WU LYF, Roberts describes that first encounter with Hoorn in characteristically dramatic terms: “Suddenly all that was once so concrete fell to sand again.”

The 25-year-old singer seems partial to entropy; he warmly reflects on WU LYF as “always being in a state of free fall.” While that band’s lone album, 2011’s Go Tell Fire to the Mountain, was a fully realized work of cavernous, cathartic riffs and howls that made good on the feverish UK-mag hype, their litany of inscrutable proclamations, PR hijinks, incomprehensible lyrics, and combative live performances made them seem built to flame out in a flash. (And for those who always thought Roberts voice veered dangerously close to overwrought Scott Stapp territory, you’re not alone. “I hadn't listened to [Go Tell Fire to the Mountain] for 18 months and I was really surprised because the vocals are fucking brutal,” Roberts tells me. “It's ridiculous.”)

Following WU LYF’s dissolution in 2012, Roberts emerged the following year with the bombastic, Clams Casino-sampling “Kerou’s Lament” (later renamed “Lament”). He describes the solo record he was working on at the time as a caustic statement inspired by Death Grips and hefty political tomes—which probably explains why he decided to shelve it. “I basically got to a point where it was giving me no joy,” he says.

LUH: "Lament (V01/2013)" (via SoundCloud)

Then, in 2014, while trying to figure the chorus of a new track with the working title “LUH Song #1,” Roberts enlisted Hoorn to sing it. Her lush tone offered a perfect complement to his inimitable growl, completely transforming the song. “That was a moment where the whole ‘thing’ of LUH started to become clear,” says Roberts, who put up that track, retitled “Unites,” on SoundCloud in the fall of that year.

LUH: "Unites (V01/2014)" (via SoundCloud)

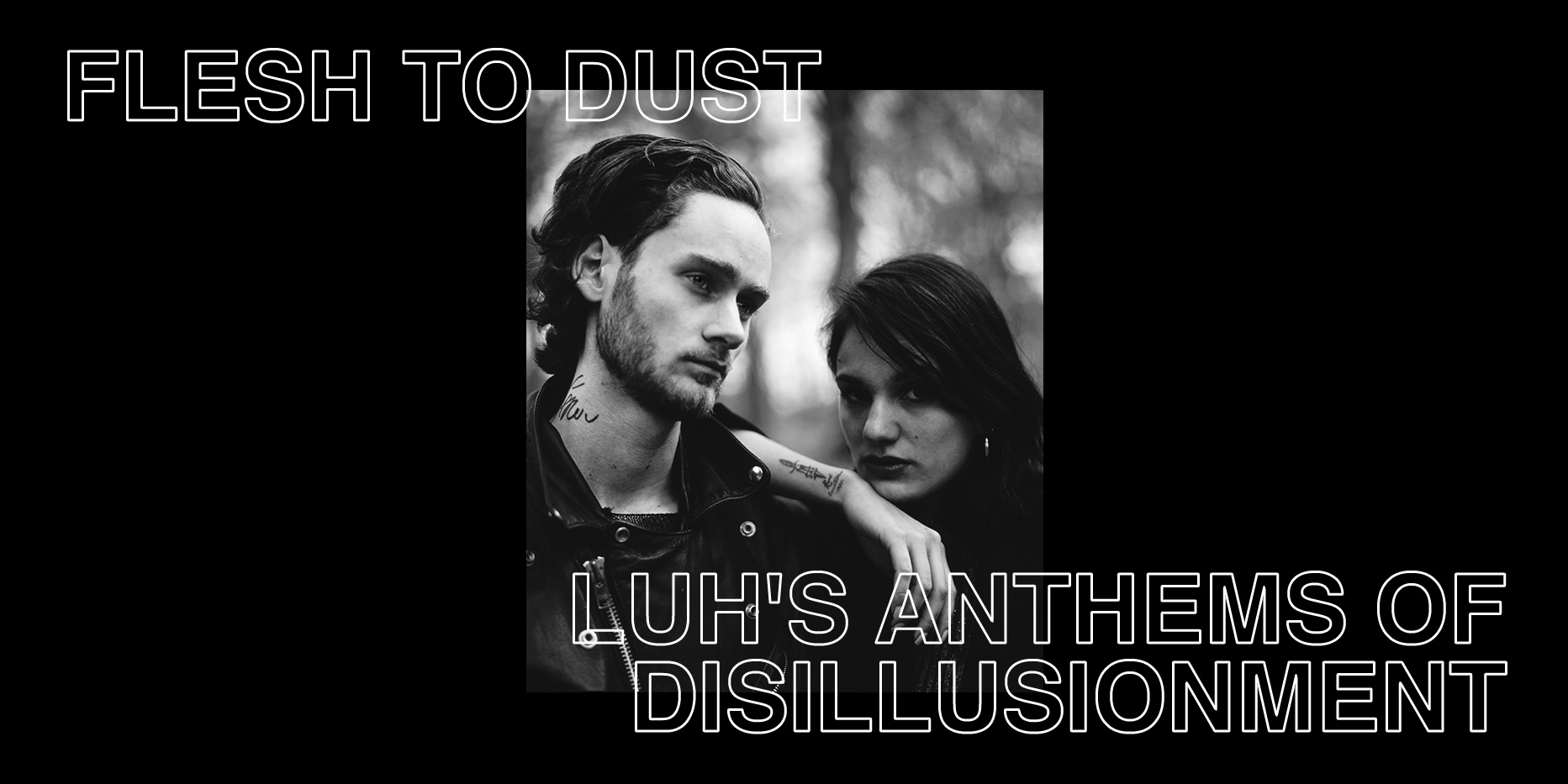

It’s around that time when I first spoke with Roberts and Hoorn via Skype. LUH stands for Lost Under Heaven, which sounds like a Young Adult Fiction novel title waiting to happen—you can instantly picture the film adaptation’s two star-crossed, gorgeous idealists fighting for their hopes and dreams against a world that is crumbling around them. Which pretty much sums up LUH in real life; when we connected, the strikingly attractive, young European couple were sitting in a Manchester flat that looked to be stuffed with books and art and little else.

At that point, near the end of 2014, LUH was in its free-form start-up phase: Hoorn and James were researching DIY and Kickstarter funding, dreaming of having their own label, and imagining expanding LUH to a seven-piece band that combined elements of Spiritualized and Fugazi. “We've got no money so we need assistance with the creative process,” Roberts admitted. To get by, Hoorn simultaneously tended bar and moved forward with her audio-visual degree as Roberts worked odd construction jobs for his father. They were staying with their friend in order to save up some money… to move back into the attic of Roberts’ childhood home, which is where they were living when they began recording their debut album last year.

The record, due out on Mute later this year, shows that their message has gotten much more loud and clear since those early demos, partly thanks to the deep, dark production of Bobby Krlic, aka the Haxan Cloak. LUH and Krlic became fast friends after a trial session and then decamped for two weeks to a cottage on Osea Island, off England’s southeastern coast, working 24/7 in a secluded studio. The producer and duo turn out to be a perfectly strange pairing, as they both have grand ambitions that go in equal and opposite directions; whereas Haxan Cloak made his name on plumbing the depths with unprecedented sub-bass, the LUH LP bursts through arena ceilings to let the heavens in, as heard on first single “I&I” as well as upgraded versions of “Lament” and “Unites.” Simply put, the whole thing sounds fucking colossal.

The couple moved to Amsterdam after completing the record, though they’ve made it a point to be just as isolated as they were on Osea as they plot their upcoming LUH tour as a four piece including DJ/multi-instrumentalist Oliver Cooper and drummer Steven Hermitt. When I catch up with them again recently, their Skype picture features Hoorn with a raised middle finger obscuring her face. They currently spend most of their time in a recouped practice space with no wireless access. “The Internet is far too wild to keep at home,” Roberts says. This decision also helps Hoorn, 24, focus on her thesis, which she says explores “solitude and times of hyper-connectivity.”

As for the thesis behind LUH, Roberts makes his case in typically lofty language, saying the band speaks to the desire “to sustain a self-sufficient culture and be able to reject the status quo, because we've got a more fulfilling thing going on away from it.” (The following Q&A is culled from both interviews with Roberts and Hoorn.)

Pitchfork: When WU LYF imploded, were you tired of the traditional rock band setup?

Ellery James Roberts: There was always a split [in WU LYF]. When we were starting, I was really inspired by the KLF and Situationists—this whole wayward troublemaker [ideal]. And then it was also just a simple band making good time rock’n’roll, like the Replacements. When we were touring, there was a conflict between those two sides, and it became a stagnant and negative relationship that was quite harmful. It made me disillusioned with the whole creative process and the power and joy music can give.

Pitchfork: Was there a specific low point?

EJR: We finished playing shows, and I went to Spain with with two old friends. We were living on a remote beach, which was really freeing, but the nearest place we could drink or do anything was an hour's walk along a cliff and through a forest. So I'm in a small shop in a provincial town along the coast of Barcelona and I hear this song. And I'm like, “Fuck, why do they play this annoying indie music?” It sounded so familiar, though—and then my vocals started. That was really the point where I was like, “This isn't what I want.” I love so much that is on the [WU LYF] record, but that just took away the momentum. It wasn't the sound of the feeling that I loved, you know?

Pitchfork: How did the idea of LUH originally come to be?

EJR: Me and Ebony went to southeast Asia for two months [in 2013], where we had no connection to the world around us, in a desire to be away from it all. When we were in Thailand, she said to me, “LUH.”

Ebony Hoorn: There was this big thunderstorm outside, and the name just popped into my head.

EJR: We made this tongue-in-cheek conceptual lifestyle brand and had this manifesto that was picking up on the cheesy spirituality in Thailand, where all these people [like us] try to find themselves and feel like they're buying the package of a spiritual journey.

Pitchfork: When you describe "Unites" as being a love song for modern times, how do you think the disillusion of now differs from the past?

EJR: What's interesting about disillusionment now is that we genuinely live in an environment where, in 30 years time, there is going to have to be significant cultural change to the social, political, and economic systems because you’ll need 70 planets or something to sustain the current lifestyles. The endgame for me is getting a house in the mountains and being able to live and create without having to take part of something. I don't enjoy making entertainment for hedonists.

Pitchfork: But after having played festivals like Coachella with WU LYF, do you see any upside to having that kind of mass outreach to spread your message?

EJR: If you look at the way Fugazi existed, for instance, that's incredibly inspiring to me.

EH: That's what you see more in hardcore.

EJR: Ebony was much more involved in hardcore growing up. That's what I aspire to: Self-sufficiency that’s not self-reliant. You're in a greater community.

"I don't enjoy making entertainment for hedonists."Ellery James Roberts

Pitchfork: Do you think the world is in a better place now than it was a couple of years ago, when you started LUH?

EH: No. And it's only becoming worse. We're very lucky to have our own platform to express ourselves and talk about things and make people aware and hand out information.

EJR: Protest music is relevant but it’s not always constructive in a sympathetic way. I feel like a constructive output is just bringing this shared experience with a community and people, like, “These are my experiences. This is what I've felt and seen in the world.” If everybody expressed what they believed in and made a conscious effort, there would be a lot more positive things in the world. Be mindful of what your belief is. Challenge it. Why do you think that? I challenged myself about going into an intellectual hole rather than being really naked and disclosed emotionally. We get in fights, and sometimes I feel like I'm turning into Woody Allen.

Pitchfork: A lot of last year’s most prominent records could double as protest music, and most of it came from hip-hop. Do you consider those records to be constructive as well as sympathetic?

EJR: The Kendrick record is incredible; Saul Williams is saying interesting things. People are angry. The majority of pop music comes from the lower classes of society—there are very few oligarch pop stars. You've got the Taylor Swift bullshit on the surface, but the real American culture is hip-hop.

Pitchfork: Do you feel Europe has a musical voice that expresses its culture the way hip-hop does in America?

EJR: I don't know because I'm not really connected with a lot of music in general. I’m sure there is something—damn it, that is what we're here for.