Longform: Chris Cornell, Searching for Solitude

Interview: Grizzly Bear Discuss Painted Ruins, Their First Album in Five Years

Lists & Guides: Loveeeeeee Songs: Rihanna's 52 Singles, Ranked

More than any pop star today, Rihanna makes it look easy. But a look at the numbers proves that her career has been anything but that: Across 12 years, eight albums, and 52 singles as a lead artist or equally billed collaborator, she has reinvented and redefined herself in incredible ways. She’s flipped from sunny Bajan princess to take-no-prisoners pop assassin, from EDM chart-topper to bawdy rap slayer, from reluctant center of tabloid scrutiny to a boss fully in charge of her own deeply enviable life. She’s arguably the most influential singer of the past decade. Hell, even Spider-Man tries to be Rihanna at this point. Here's our list of her best radio moments—all of Rihanna's singles, ranked.

“Birthday Cake” [ft. Chris Brown]

Talk That Talk

Def Jam Recordings, 2012

Out of context, “Birthday Cake” isn’t remarkable, with Chris Brown being an R&B star and Rihanna being perpetually in the market for R&B songs and collabs. But this particular collaboration stunk of the thoroughly cynical publicity stunt it was executed as. That “Cake” already lurched between lascivious and predatory, a provocation anchored by “I’mma make you my bitch,” just made its rewrite as a grand Rihanna/Chris sexual reunion sound that much more cold and wrong. But it wasn’t personal, just business—and, in true business fashion, it was killed unceremoniously when Brown’s sales faded and Rihanna got urban-radio cred instead. Happy birthday! –Katherine St. Asaph

“Sledgehammer”

From the Motion Picture “Star Trek Beyond”

Westbury Road Entertainment, 2016

Here lies Rihanna’s least successful power-piano ballad, tacked onto a sci-fi epic that doesn’t fit it. (Do they even have pianos in the future? Or sledgehammers?) To be fair, it contains many of the same elements that have garnered Rihanna amazing results elsewhere: As the song opens, her vocal is throaty and compelling and the lyrics moody and confessional, with a magnetic, building tension. But nothing in its emotional or lyrical content justifies the will-to-bigness of the pounding chords and nearly shouted chorus. Even Rihanna seems a bit distant from the galactic importance she’s placing on this song. If the titular weapon was chosen to embody blunt power, the motif that actually stays with you is Rihanna wailing, “I hit a wall! I hit a wall!”—conveying the unfortunate impression that this song was a cry for help from her writing team. –Edwin “STATS” Houghton

Listen: “Sledgehammer”

“Talk That Talk” [ft. Jay Z]

Talk That Talk

Island Def Jam, 2012

On paper, “Talk That Talk” sounds like a pretty good deal: Jay Z and Rihanna trading sexually charged bars over Stargate production. The track opens with catchy Nintendo synths and trap drums; a Coldplay-ish melody fleshes out the beat as Jay speaks his clout and Rihanna intones, distantly, “Yeah, boy, I like it.” That underpaid-porn-star ennui says it all: As an invitation to be inventively naughty, “Talk That Talk” feels formulaic and tame, employing many of the same bits of ear candy that make “Rude Boy” such a great song without any of that hit’s originality or urgency. –ESH

Listen: “Talk That Talk” [ft. Jay Z]

“Redemption Song” (For Haiti Relief) [Live from Oprah]

Island Def Jam, 2010

Rihanna was a longtime fan of “Redemption Song”—she had covered Bob Marley & the Wailers’ song of upliftbefore 2010, when she released her recording of it as a charity single for Haiti after the country’s devastating earthquake. She talked about the song’s personal meaning during itslive premiere on Oprah before delivering a serviceable if largely forgettable performance. Though there’s something to be appreciated in the cross-cultural aspect, aside from charitable contribution, there’s little incentive here to deviate from Marley’s original. –Briana Younger

Listen:“Redemption Song” (For Haiti Relief) [Live from Oprah]

“Wait Your Turn”

Rated R

Def Jam Recordings, 2009

Over an ominous, marching beat, Rihanna’s chant of “The wait is ova” repeats, uh, ova and ova without much resolution or even excitement. A generic banger every now and then is fine, but “Wait You Turn” never even attains that status. Not canon. –Rebecca Haithcoat

Listen:“Wait Your Turn”

“Towards the Sun”

Home (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack)

DreamWorks Animation/Westbury Road, 2015

As pop anthems with pretensions of grandeur go, “Towards the Sun” is not a bad one, really: It’s a soundscape crafted as meticulously as any lite-FM hit, created for the alien invasion cartoon Home (for which Rih voiced a character). In going high-note-for-high-note with a full choir of castrato voices on the weirdly ascending refrain, Rihanna sets herself a particularly difficult vocal challenge, and she executes it with admirable grace. The hook stands out from her usual arsenal, but it also feels emotionally removed from the real Rihanna oeuvre and the themes she’s explored in it. “Towards the Sun” serves its cartoon concept, and might even inspire a quick falsetto sing-along if you happened upon it, but you’d have to be a truly obsessive Rihanna completist to seek it out. –ESH

Listen: “Towards the Sun”

“Rockstar 101” [ft. Slash]

Rated R

Island Def Jam, 2009

Every pop star eventually releases something like “Rockstar 101,” collaborating with a classic-rock legend with wildly varying intents and results. (Peak: Kesha and Iggy Pop. Nadir: Mick Jagger and anyone he collaborated with past 2000). While “Rockstar 101” was roundly laughed off at the time, in retrospect, Rihanna demonstrates early signs of indifferent swagger and the genre reclamation she’d repeat more mutedly in “FourFiveSeconds.” The most rockstar move here might be relegating Slash to background squall. It signified that the R in Rated R might as well have been “reinvention”: taking an artist still known for lightweight dance songs into territory that was tougher, rougher, badder. –KSA

Listen:“Rockstar 101” [ft. Slash]

“Right Now” [ft. David Guetta]

Unapologetic

Island Def Jam, 2012

With a space-age, swelling EDM beat courtesy of David Guetta, this mammoth track seemed ready-made for raking millions soundtracking advertising campaigns. It quickly wound up as the intro music for the2013 NBA Playoffs and in Budweiser’s “Made for Music” campaign. It isn’t a particularly memorable piece of her catalog, but Rihanna is nothing if not capable of always securing the bag. –BY

“American Oxygen”

Westbury Road, 2015

What to do with “American Oxygen”? While it finds Rihanna spreading her wings to address big themes, it too often feels like a self-conscious attempt to write her into the American songbook of patriotic heartbreak—the one boasting Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.”and Jimi Hendrix’ “Star Spangled Banner”—with wobbles and 808 kicks replacing guitar feedback. Although touching on something important—particularly in the line, “We sweat for a nickel and a dime/Turn it into an empire”—the song builds without delivering emotionally or conceptually. Still, Rihanna stretches thematically here, and with her moody vocal around heavy minor chords, “American Oxygen” is the sound of her feeling out a particular mode that she has taken to sublime levels elsewhere: the ambivalent anthem. –ESH

Listen:“American Oxygen”

“Te Amo”

Rated R

Island Def Jam, 2009

Rihanna loves turning convention on its head, and on “Te Amo,” she imagines unrequited love between two women. The track, which never made much noise in the U.S., finds Rihanna struggling as the object of another woman’s affection. The slick, electro-Latin track was of special interest when the video came out—it features the former Victoria’s Secret model Laetitia Casta as a femme fatale in love with our hero. –RH

Listen:“Te Amo”

“What Now”

Unapologetic

Island Def Jam, 2012

This song is all about contrasting binaries: delicate piano collides with roaring cymbal and bass as Rihanna’s sweet singing erupts into full belting. Only an artist with a voice as unique as Rih’s could pull off the dueling vocals without sacrificing emotion on either end. Even though it got the single and video treatment, “What Now” still feels criminally slept on. –Briana Younger

Listen: “What Now”

“California King Bed”

Loud

Island Def Jam, 2010

Possibly worse than any breakup is the torturous period before it, that time spent prolonging the inevitable. It’s one of those feelings only recognizable to those who’ve experienced it, but Rihanna captures it perfectly in this rock serenade, its splashy guitars provide a glittering backdrop for her classic diva chops. For all of her bombastic EDM and pop singles, the softer sides of the singer have provided some of her most arresting moments. –BY

Listen:“California King Bed”

“Break It Off” [ft. Sean Paul]

A Girl Like Me

Island Def Jam, 2006

The elements of “Break It Off” aren’t rocket science: This is an overtly sexual, eminently danceable club song. The beat is an innovative and deceptively simple trap-soca hybrid that splits the candy-painted synths and 808 palette of the Atlanta club sound with triple-time drums. The chemistry between Sean Paul and Rihanna works; showing her Afro-Caribbean roots always seems to bring something extra from her. None of these elements surpass the best solo work of each vocalist, and as a duet, it’s far overshadowed by Rihanna’s later work with Drake, but each element does exactly what it needs to achieve thrust. –ESH

Listen: “Break It Off” [ft. Sean Paul]

“Nothing Is Promised” [w/ Mike WiLL Made-It]

Ransom 2

Westbury Road/Interscope, 2016

The myth of Rihanna is that she does whatever the fuck she wants, when she wants, so her slurred verses on “Nothing Is Promised” snap nicely into that image. Breezing through a Mike WiLL Made-It beat that sounds earmarked for Future—chiming bells, glistening trap drums—she makes like a rapper, loosening her tongue and spitting flossy bars with blurry words cowritten by Future. Also interesting here is the edge to Rih’s voice, which replaces the playfulness she usually employs. “I’m past niggas,” she purrs. “I love you, money.” Two can play at this game, and at least on “Nothing,” it’s cash flow over bros. –RH

Listen: “Nothing Is Promised”

“Unfaithful”

A Girl Like Me

Island Def Jam, 2006

R&B is full of men trying to atone for their indiscretions and women trying to navigate the aftermath but, every now and then, the tables turn. Twisting this entire dynamic on its face, Rihanna is apologetic but also content to continue with her cheating ways, likening the act to murder. Like her character, her voice is imperfect but redemptive, spilling out over orchestral strings and piano that give the song’s doom and gloom a noble sheen. Infidelity never sounded so charmingly reflective. –BY

Listen:“Unfaithful”

“Princess of China” [w/ Coldplay]

Mylo Xyloto

Parlophone Records, 2011

If there were a list of unexpected Rihanna collaborations, this one with Coldplay would fall in the top percentile. Their voices blend surprisingly, casually well, content to let the production claim most of the spotlight. The song is executed quite well, considering the combination of otherwise disparate styles. The skittering synths and pulsating bass make this flamboyant breakup song readymade for a finale at Electric Daisy Carnival. –BY

Listen: “Princess of China”

“Cheers (Drink to That)”

Loud

Island Def Jam, 2012

Of all the Loud singles, “Cheers” fits best with the Rihanna of today, finding her leaning both into patois and blasé cool. Said cool comes mostly secondhand, via nods to“Ignition (Remix),”“Gin and Juice,” Coyote Ugly, a great deal of product placement and, of course Avril Lavigne’s “I’m With You” (the latter via a garish, unignorable sample). At least “Cheers” knows exactly what is and doesn’t try to be anything else; toward the end, it cuts to a presumably drunken last-call singalong, the song’s natural habitat. After all, one constant in life is that no matter what shit happens Monday to Friday, there will always be another freakin’ weekend, and people need to drink to something. –KSA

Listen:“Cheers (Drink to That)”

“Breakin’ Dishes”

Good Girl Gone Bad

Island Def Jam, 2007

Good Girl Gone Bad, to its credit, goes past sexy-baby mode—that clichédpop star’s sexual awakening narrative—and includes actual and awesome acts of girls going bad. This track itself is slight, with Tricky Stewart and The-Dream on autopilot, but it includes Rihanna rapping about smashing dishes, bleaching and burning her man’s clothes, and torching the house. All this for someone who Rih admits might not actually be cheating (“Man, I don’t know”). It’s Rihanna’s very own “Ring the Alarm,” and almost as bracing. –KSA

Listen:“Breakin’ Dishes”

“We Ride”

A Girl Like Me

Island Def Jam, 2006

It’s odd now to hear Rihanna on such a bubblegum single—even “Pon de Replay” has swagger to it—but it’s not like it doesn’t work. “We Ride” draws upon 2000s R&B and bubblegum pop to turn a ride-or-die lyric into a wistful, swooning plaint to a less-than-devoted lover, nestling this among wisps of backing vocals, acoustic guitar, and twitchy percussion just this side of trap. “We Ride” wasn’t on Music of the Sun,but it sounds like the sun. – KSA

Listen:“We Ride”

“Raining Men” [ft. Nicki Minaj]

Loud

Island Def Jam, 2010

The glossy trap sheen and theatrical Nicki Minaj guest verse are excellent distractions from the fact that this is a rip-off of Beyoncé’s “Diva.” Still, plenty of people will forgive rip-offs (ahem, “Fancy”). But while Rihanna’s voice sounds as cozy as a blanket on a dreary day, she’s not saying much, and she’s saying what remains without any real conviction, which is probably why “Raining Men” never cracked the Billboard Hot 100. –RH

Listen: “Raining Men” [ft. Nicki Minaj]

“Hate That I Love You” [ft. Ne-Yo]

Good Girl Gone Bad

Island Def Jam, 2007

It’s not hard to picture Rihanna and Ne-Yo staring into each other’s eyes as they recorded this sweet duet—their harmonies are heartfelt, and their synergy feels organic. Rih’s voice retains its teenage innocence on this bittersweet love song that ultimately ends up on the softer side. Unfortunately, it largely sounds like a remix of Ne-Yo’s “So Sick,” which takes away from its potential to be a truly standout Rih record. –Briana Younger

“If It’s Lovin’ That You Want”

Music of the Sun

Island Def Jam, 2005

Adroitly flipping Boogie Down Productions’ Bronx patois, Rihanna’s vocal transforms toughness into a breezy, catchy melody—an early indicator of how she would soon balance hip-hop, pop, and her West Indian roots in a way that felt genuine and effortless. Even her slight pitchiness on the song’s bridge feels like growing pains that serve the overall puppy-love vibe. “If It’s Lovin’” still fits firmly into the radio-ready template established by “Pon De Replay,” and it gave us a compelling early glimpse at the woman Robyn Rihanna Fenty would become. –ESH

Listen: “If It’s Lovin’ That You Want”

“Rehab” [ft. Justin Timberlake]

Good Girl Gone Bad: Reloaded

Island Def Jam, 2008

Instead of leaving it to industry suits, who never miss a Lolita opportunity, Rihanna herself steered the project that sought to sex up her image, Good Girl Gone Bad. Yet she never really had an “innocent” image to sully; even in her early videos, there was a knowing gleam in her eye. It’s why she’s able to pull off “Rehab,” a song that would’ve been a bit mature for any other 18-year-old to record, and why she doesn’t wilt next to Justin Timberlake—no small feat, considering he wrote and co-produced the song, and he was coming off 2006’s FutureSex/LoveSounds. Here Rihanna doesn’t rely on any expected theatrics, playing it straight, which instantly heightens the drama. Singing almost in a monotone, she allows the exhaustion and anguish of addiction to rise to the surface. The song is fine, but the shrewd, early creative control is what’s really notable here, as a harbinger of things to come. –RH

“Disturbia”

Good Girl Gone Bad: Reloaded

Island Def Jam, 2008

One of those weird synchronicities: a phrase popularized in a 1961 bestseller about Cold War suburban malaise bubbled up twice, a few decades later, in a Shia LaBeouf film and a Rihanna single. The former went with the suburban angle, but the disturbia on offer from RiRi is straight from the co-writer Chris Brown’s head. Inevitably, it doesn’t entirely hold up; Brown’s subsequent decade shrouds “Disturbia” in now-unavoidable subtext, and Rihanna’s delivery of dense lyrics like, “If you must be falter, be wise” come off as the least convincing philosophical koans in history. But out of this context, “Disturbia” is still plenty disturbing, largely because Rihanna avoids histrionics: inhabiting a remarkably dark dance track without ado, singing about nightmares and monsters as if they’re all too familiar. Even the introductory horror-film scream is low-key. –KSA

Listen: “Disturbia”

“S&M”

Loud

Island Def Jam, 2010

In which Rihanna re-uses the electro stomp of “SOS” to exult in a different sort of tainted love. Songwriter Ester Dean’s topline may be lyrical fetish dress-up, but it’s perfectly good at it—it’s more explicit, anyway, than anything that arrived years later on the soundtrack to Fifty Shades of Grey. Rihanna’s more than game; the song is really more of a bottom thing, but Rihanna unquestionably dominates it, with growly gusto and impish glee. But the less said about the remix, featuring a narcotized Britney Spears, or video director Melina Matsoukas’ porno parody of Chicago’s “We Both Reached for the Gun,” the better. –KSA

Listen: “S&M”

“Where Have You Been”

Talk That Talk

Island Def Jam, 2011

“Where Have You Been” is a fairly blatant attempt to recapture the club juice of “We Found Love”—producers Cirkut and Dr. Luke even sneak in that Calvin Harris drop toward the end—but it’s really the grown-up version of “Don’t Stop the Music.” There’s no more coyness, no more surprises, just a monomaniacal focus on dancing your way to get what you like. (What the market likes, too: The eh-ehs of the pre-chorus are a clear “Umbrella” nod.) It’s the moment EDM Rihanna reached critical mass, as widely and shamelessly as possible—and with the presence she developed over the past half-decade or so, she made it work. –KSA

Listen: “Where Have You Been”

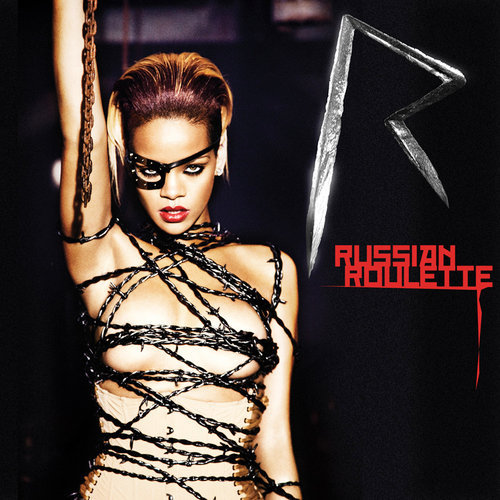

“Russian Roulette”

Rated R

Island Def Jam, 2009

Those of us given to darkness are drawn to the ominous “Russian Roulette” and the revelation of a Rihanna unafraid of her own shadows. The bass resembles a heartbeat, slow and steady despite the growing tension around it, heightened by the dice and revolver accents. Melodramatic? Sure, but the metaphor of falling in love as a game of Russian roulette doesn’t seem that off-base—at least not to someone who’d just been through what Rih had. Her voice quivers ever-so-slightly as she sings, and even though the whole scene is overdone, it captures exactly what it set it out to do. –BY

Listen: “Russian Roulette”

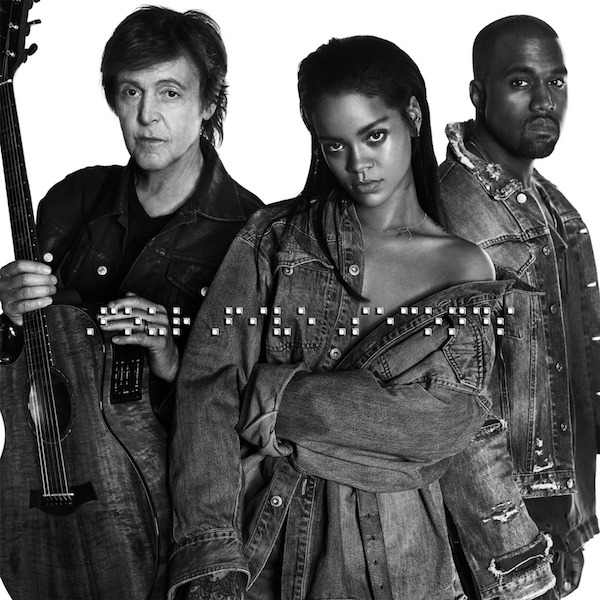

“FourFiveSeconds” [w/ Kanye West and Paul McCartney]

Westbury Road, 2015

This one is for everybody who doubted Rihanna could sing. With its stripped-down production, this “wait, what?” collaboration between Rihanna, Kanye West, and Paul McCartney has no Auto-Tuned nooks or bass-filled crannies in which to hide. Not that Rihanna needs to—hear that little mouse of a squeak in her first lines? The Sunday morning gospel belt over the organ? We rarely hear Rih’s voice in the wild, but those beautiful imperfections make us hope that this won’t be the last time. –RH

Listen:“FourFiveSeconds”

“Shut Up and Drive”

Good Girl Gone Bad

Island Def Jam, 2007

Cranked with New Order’s “Blue Monday” sample, “Shut Up and Drive” is familiar, but its popularity also is due to Rihanna’s early, emergent sex-positive identity. Her vocals are thin here and the lyrics—lots of double entendre car talk—are laughably obvious. Yet there’s still a molasses warmth to her voice that’s a welcome respite from the bubblegum blandness of many young, female pop stars. –RH

Listen: “Shut Up and Drive”

“Hard” [ft. Jeezy]

Rated R

Island Def Jam, 2009

For many of her fans, Rihanna is at her best when she’s at her cockiest, and “Hard” was an early taste of just how grand the singer’s bravado can be. She isn’t nearly as convincing here as she would later become, but the synth and tinkling piano in The-Dream and Tricky Stewart’s production, coupled with the guest verse by Jeezy, give the song some extra edge. At the time, the belligerence was a gratifying moment for people thirsty for Rihanna to emerge impervious following the fateful 2009 Grammys. Needless to say, her prophetic “that Rihanna reign just won’t let up” line has aged very well. –BY

Listen:“Hard” [ft. Jeezy]

“Sex With Me”

ANTI

Westbury Road, 2016

That sex sells is old news, but this ANTI bonus track is so deliciously shameless, it should’ve been given priority placement on the original edition. Rihanna is teasing and playful, completely aware of the fantasies she arouses, and she wields her sexuality better than any other pop star. It’s not a gimmick or tool but something she authentically embodies, existing to be manipulated only by its owner as she wishes, and her enjoyment is more than clear. –BY

Listen:“Sex With Me”

“Cockiness (Love It)” (Remix) [ft. A$AP Rocky]

A$AP Rockyrides a tweaked-out beat by Bangladesh in gloriously jiggy fashion, but it’s Rihanna’s aerobic delivery of a checklist of nearly-unmentionable acts (“suck my cockiness”) that jerks you to attention. Rihanna raps like a cartoon character, her rubber-band mouth stretching out and popping back into place with these sly, sexed-up phrases. It’s risqué and funny and smart and smartass—and, most surprisingly, sexy. –RH

“Man Down”

Loud

Island Def Jam, 2010

“Man Down” will be remembered as one of the moments when Rihanna truly came into her own as an artist. Minting new fans across cultural and generational lines, the song works on many levels. The beat is a note-perfect tribute to the digitized reggae anthems of the ’90s; the lyrics are deliberately constructed as an answer to Bob Marley& the Wailers’ “I Shot the Sheriff.” It’s also one of Rihanna’s strongest vocal performances, a case where her natural Bajan patois and slight country twang perfectly frame the emotional immediacy. All these layers, however, hold up the urgent chorus, which, read literally, upends the misogynistic “Gz Up, Hoes Down” ethos of so much modern R&B, boldly articulating a pose that’s since become Rihanna’s resting stance.–Edwin “STATS” Houghton

Listen: “Man Down”

“SOS”

A Girl Like Me

Island Def Jam, 2006

Among the most maligned producers of the late ’00s was J.R. Rotem, known for big, unsubtle samples like Jason Derulo’s flip of Imogen Heap’s “Hide and Seek” and Sean Kingston’s lifting of “Stand By Me.” But sometimes big, unsubtle samples work, and “SOS”—an early hit for both Rotem and Rih—lifts the stomps of Soft Cell’s “Tainted Love” but ditches the Northern Soul torch song attached to them. The lyrics in its place aren’t great, with clumsy scansion and over-cleverness (“Feel this way-O-U are…”), so she alternately autopilots and karaokes through them. But the beat is undeniable: It’s the moment critics began to take Rihanna seriously. –KSA

Listen:“SOS”

“Take a Bow”

Good Girl Gone Bad: Reloaded

Island Def Jam, 2008

“Take a Bow” is one of the most relatable singles Rihanna has released. It unambiguously captures the way hurt masquerades as anger after a failed relationship. There’s a sense of sorrowful relief each time she sings, “But it’s over now,” and that familiar feeling sticks long after the song ends. Though the naiveté in “Take a Bow” is unimaginable for today’s Rih, it was believable coming from her then-20-year-old lips. Like most of her lovelorn ballads, it’s a rare and humanizing moment for a larger-than-life persona. –BY

Listen:“Take a Bow”

“You Da One”

Talk That Talk

Island Def Jam, 2011

Rihanna has always been radio-friendly, but Talk That Talk, her sixth studio album, was racier fare: No matter how creatively rendered, no song with the lyric “suck my cock” is making it on the air. The exception is “You Da One,” the sweet, Dr. Luke-produced mid-tempo bouncer. Its lyrics are a little generic, especially considering the album’s other tracks, but its backdrop is a cloudless Caribbean day, and the midnight spell of “We Found Love” needed that balance. –RH

Listen:“You Da One”

“Don't Stop the Music”

Good Girl Gone Bad

Island Def Jam, 2007

Good Girl Gone Bad’s fourth single is also its most obvious retread. It pulls the same trick as its spiritual predecessor, “SOS,” plucking a dance cover from the ’80s for even further EDMification—in this case, Michael Jackson’s “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’,” specifically the breakdown from the Cameroonian jazz-funk artist Manu Dibango. But producers Stargate, who would work with Rihanna for years, take Dibango’s block-party exuberance and Jackson’s handclaps and jack up the contrast: a ruthless four-on-the-floor heightened and sharpened from its source material. What would otherwise just be the umpteenth self-referential plea to a DJ becomes driven, even desperate; it's not a night out but a mission. –KSA

Listen:“Don't Stop the Music”

“What’s My Name” [ft. Drake]

Loud

Island Def Jam, 2010

In a country of prudes and secret porn obsessives, Rihanna’s open embrace of her sexuality is like that first inhale of air after you’ve left a smoggy city. Like Madonna, Rihanna knows there’s power in submission, but she’s comfortable playing both positions in the flirty, R&B-flavored confection “What’s My Name.” (That “oh na, na” cry immediately recalls the “na na, you can’t get me” playground taunt.) Toying with gender roles even more, she flips the rap script and demands Drake say her name. A singsong melody on the hook means everybody kept asking her from them on. –RH

Listen: “What’s My Name” [ft. Drake]

“Pon De Replay”

Music of the Sun

Island Def Jam, 2005

Ironically, the song that launched one of pop music’s great voices was almost entirely about the beat. Jay Z, who signed Rihanna partially on the strength of her “Pon De Replay” demo, later revealed that he almost passed because he felt the song was “too big for her.” Indeed, with its catchy “Hey, Mr. DJ” hook and a beat that drew heavily from dancehall, “Pon De Replay” seemed destined to be a club hit that would define its singer. And though the track launched an artist of much greater versatility than its “one by one, even two by two” bars might suggest, her effortless facility in riding a riddim also signaled that, no matter how far she roved, dancehall would always be in her DNA. –ESH

Listen: “Pon De Replay”

“Love on the Brain”

ANTI

Westbury Road, 2016

While much of ANTI is driven by Rihanna’s soulful interpretation of mumble-rap, the retro doo-wop of “Love on the Brain”—reportedly the first song written for the album—fits right in. A classic torch song, it shows off Rihanna’s mature vocal range, swelling from a scratchy, whispering scat worthy of Ella Fitzgerald into gut-bucket blues, downshifting to a whimsical, Prince-worthy bridge. This is so far stylistically from the up-to-the-nanosecond sound of “Needed Me,” you could be forgiven for mistaking RiRi for someone else entirely. –ESH

Listen: “Love on the Brain”

“Stay”

Unapologetic

Island Def Jam, 2012

“Stay” may be Rihanna’s most powerful ballad to date. Its spareness allows her to show her full range of idiosyncratic vocal modes, which move from warm, crooning whisper to soaring power-notes imbued with an icy numbness, then break with emotion at just the right moments. Songwriter Mikky Ekko’s shrill falsetto makes an unlikely but extremely effective counterpoint to this virtuoso performance, but even though it’s his song, it’s really her performance. Rihanna feels so comfortable, so in control of her technique, that she delivers a kind of sonic method acting. While the reverent chorus, “I want you to stay” follows a great tradition of ballads, everything here feels new, raw, and honest. –ESH

Listen: “Stay”

“Loveeeeeee Song” [ft. Future]

Unapologetic

Island Def Jam, 2012

Sleek and star-streaked yet still imbued with warmth, “Loveeeeeee Song” is a modern love duet that deals in that most classic of pairings—the rapper and the R&B singer. In 2012, Future had yet to get his heart broken by a different R&B star, and Rihanna was considering reconciling with Chris Brown, so they were only lovers on wax. Still, both sound like they’ve ripped these feelings up from the very roots, and the pairing of Future’s warbled yodel and Rihanna’s rich, throaty voice is oddly satisfying. That her voice was perhaps so choked with emotion over Brown, less so. –RH

“Only Girl (In the World)”

Loud

Island Def Jam, 2010

Rihanna’s no-fucks-given image is a relatively recent invention, and “Only Girl (In the World)” is when Rihanna gave all the fucks (in the world). It’s built on the same electro chassis as her late-’00s singles, but twitchier, more anxious, and more suited to pleading vocals; the lyrics are about hugging pillows and setting clingy traps, capped by a loud, belted feelings-bomb of a chorus. It’s the missing link between the house-diva emoting of the ’90s and the big, earnest feelings so ubiquitous in today’s festival EDM hooks. –KSA

Listen:“Only Girl (In the World)”

“Kiss It Better”

ANTI

Westbury Road, 2016

Emotional turmoil and sensuality are hard to combine in one song, but on “Kiss It Better,” Rihanna ups the ante, effectively flashing conceit and vulnerability in the same breath. She is both asking and expecting that her old lover will return to her side, and her smoky vocals, desperate but measured, make a convincing bid. But for once, Rih isn’t the only star here: Nuno Bettencourt’s mesmerizing electric guitar riff drives the song, recalling the best ’80s rock-pop ballad Prince never played. This is a strong contender for the best break-up-to-make-up song in her arsenal. –BY

Listen:“Kiss It Better”

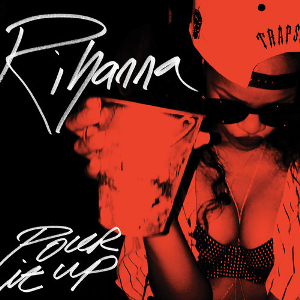

“Pour It Up”

Unapologetic

Island Def Jam, 2012

Rihanna, as we now know her, begins here. A collaboration with imperial-period Mike WiLL Made-It, who was fresh off Juicy J’s “Bandz a Make Her Dance,” “Pour It Up” takes Rihanna deep into a strip-club grotto in aboat made of money. What seemed like another dreary track on Unapologetic, an album full of them, took on new and very long life on urban radio. And Rihanna—luxuriating in her throaty, commanding lower register and her 360-deal largesse that she damn well earned, thank you—had never sounded more convincing. –KSA

Listen:“Pour It Up”

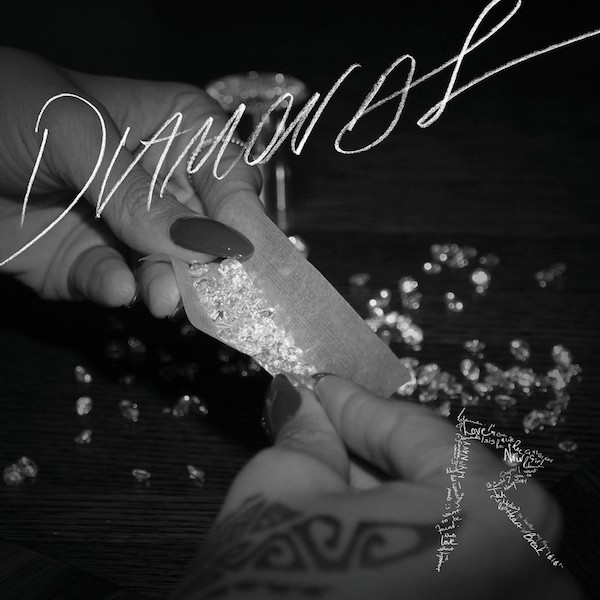

“Diamonds”

Unapologetic

Island Def Jam, 2012

Rihanna’s catalog is riddled with songs that reflect her troubled relationship with love, but “Diamonds” is a true diamond in the rough. The Sia-penned ballad put previously unmatched pressure on Rih’s vocal capacity, and she gracefully rose to the occasion. With triumphal but unobtrusive production, the Unapologetic single emphasizes her singing over all else for a result that is equal parts tender and regal. “Diamonds” added a notch of versatility to Rih’s belt for its subtlety and sentimental lyrics—and for someone whose private moments have been on full display, hearing her declare “I choose to be happy” will never get old. –BY

Listen:“Diamonds”

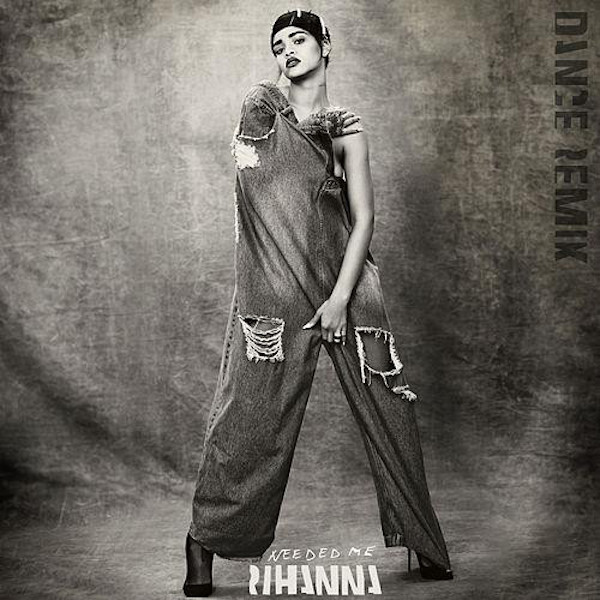

“Needed Me”

ANTI

Westbury Road, 2016

“Needed Me” is deceptively simple, an anti-tour de force. Apart from its taunting, haunting hook, it is less a song than a wisp of sonic smoke. The minimalist beat is something of a surprise, coming from trap-pop king DJ Mustard, all echoing atmospheric synths and disembodied voices. The verses are verbal daggers spoken melodically (“Didn’t they tell you that I was a savage/Fuck your white horse and a carriage”). It’s all intensely satisfying to listen to, as it takes the themes that run through much of Rihanna’s songs to their logical and inescapable conclusion, articulated with pure confidence.–ESH

Listen: “Needed Me”

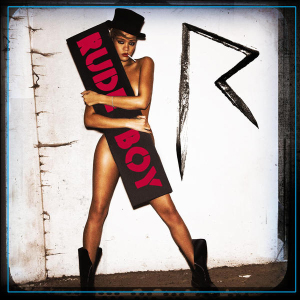

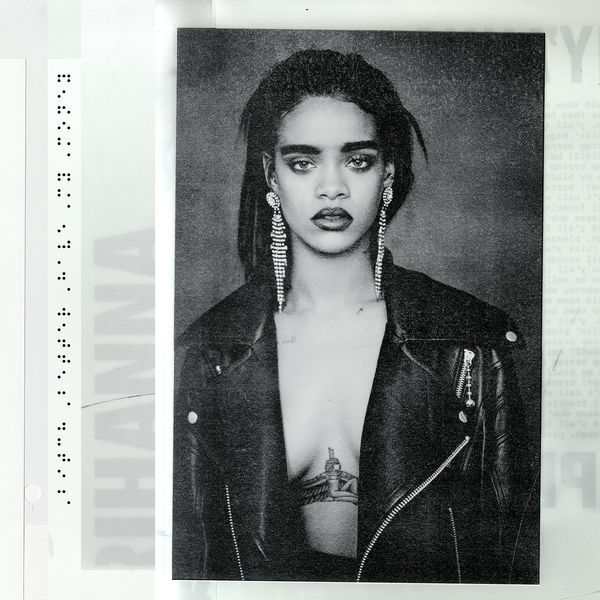

“Rude Boy”

Rated R

Island Def Jam, 2009

Other songs in Rihanna’s catalog better showcase her ever-improving voice or lyrics, but few capture her essence like “Rude Boy.” Released in 2009, almost five years after “Pon de Replay” dropped, “Rude Boy” felt like an introduction to a brand-new artist. Before, she’d played by the rules, but something had snapped, and Rihanna now shook off any regard for other people’s opinions. The sly “Rude Boy” proved she’d been miscast as the sweet pop princess pumping out senior prom anthems like “Umbrella,” and she had come into her own: Strutting out to a clipped, breezy R&B-flecked dancehall track that wriggles down into your hips, she’s cheeky and ballsy, a little bit raunchy, and at complete ease with her sexuality. “Babe, if I don’t feel it, I ain’t fakin’,” she sings. And she hasn’t since. –RH

Listen:“Rude Boy”

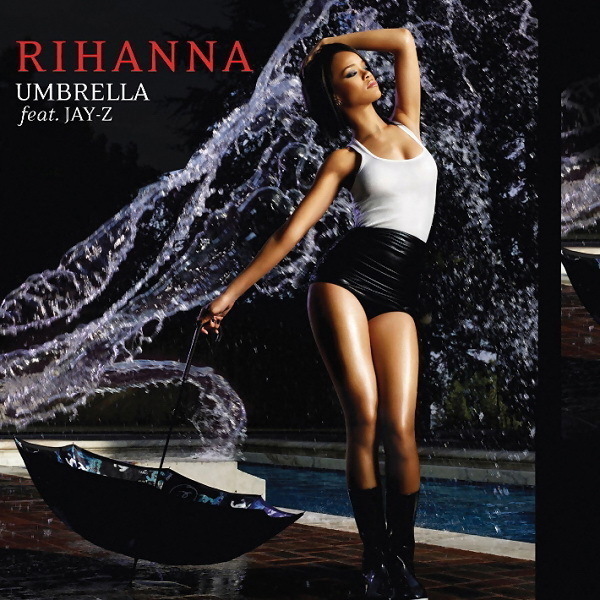

“Umbrella” [ft. Jay Z]

Good Girl Gone Bad

Island Def Jam, 2007

Although it’s arguable that anybody could have scored a world-changing hit with the catchiest song The-Dream and Tricky Stewart ever wrote—including Britney Spears and Mary J. Blige, both candidates for the track—Rihanna is the one who actually did it. (Several nations, in fact, blamed her for ruining their weather in 2007.) Rihanna’s electric-cool interpretation of the melody not only gives extra power to the moments where she lets the warm grain of her voice show through, it moves it completely beyond The-Dream’s signature doo-wop feel, opening up a whole new dimension to the text. Ultimately, the tension between her icy detachment and the girly innocence of the singsong “ella-ella-ay” refrain is what drives the song, undercutting the invitation of the lyric but creating a feeling of soaring untouchability that perfectly matches the theme of Jay Z’s “fly higher than weather” verse. Rihanna renders any other singer of this song unthinkable. –ESH

Listen: “Umbrella” [ft. Jay Z]

“Bitch Better Have My Money”

Westbury Road, 2015

Part of Rihanna’s allure has always been rooted in her enviable ability to be a living, breathing middle finger, but “Bitch Better Have My Money” is bad gal RiRi at her absolute baddest. (Andthat video? A cinematic achievement.) There are no cute metaphors hiding here, only Rih asserting herself like the boss she is. Her voice brash and pitiless as she demands to be paid. The production crashes with urgency; the lyrics, courtesy of the equally badass Bibi Bourelly, are a call to arms. This track will forever ring out in clubs where the ladies are dressed to destroy whomever dares look at them too long, holding their drinks in one hand and flexing all night long. –BY

Listen:“Bitch Better Have My Money”

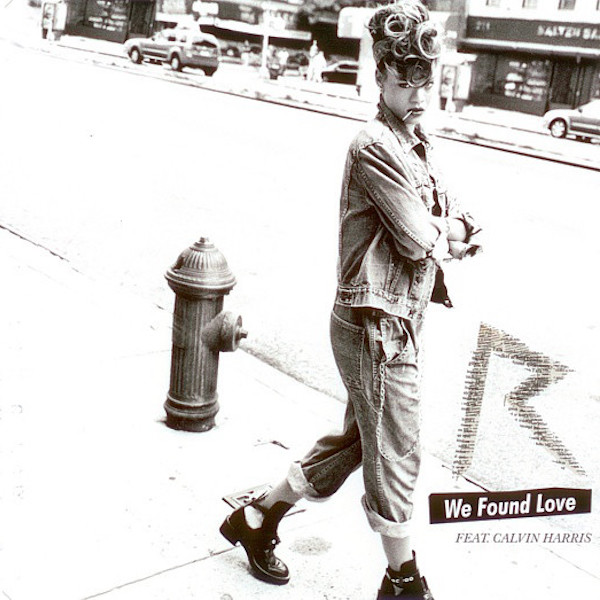

“We Found Love” [ft. Calvin Harris]

Talk That Talk

Island Def Jam, 2011

Most pop songs are more than the sum of their parts, but “We Found Love” is especially so: A peppy, EDM merry-go-round of a Calvin Harris track that became the Calvin Harris track, imitated endlessly (often by Harris himself) until it made radio a hopeless place; a melody intended fornonentities by comparison, like Leona Lewis and Nicole Scherzinger. The event video took the teenage wasteland of “Skins” and spritzed it with a little autobiography, both short-term (Rihanna reportedly dated the video lead for about five seconds) and long (the parallels between the video’s rocky-at-best relationship and Rihanna’s past were not accidental). But as she’s done so often, Rihanna found magic in an identikit place; the song’s repetitive like a pet name is repetitive, a romanticism born of comfort that you can still dance to. –KSA

Listen:“We Found Love”

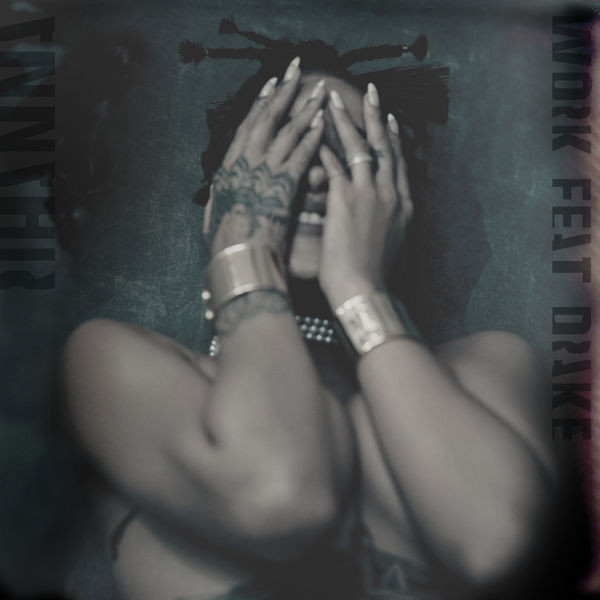

“Work” [ft. Drake]

ANTI

Westbury Road, 2016

In many ways, “Work” feels like the song Rihanna has been feeling her way towards throughout her career. Where “Pon De Replay,” her introduction to the world stage, rode heavily on Afro-Caribbean trends, “Work” has spawned its own imitators in dancehall and pop spheres. If “Replay” appealed by stressing Rihanna’s natural Bajan cadence, “Work” finds her feeling out a faded, diasporic patois that screws together rap and Kingstonian slang into a voice that is distinctively hers. If “Replay” achieved infectious catchiness at the expense of lyrical depth, “Work” manages to be both instantly hummable and emotionally subtle; it captures the small triumphs and heartbreaks of real relationships (“You took my heart and my keys and my patience”) and the energy required to maintain them (“Recognize I’m trying, baby/I have to work, work, work”).

That one-word chorus is so perfectly Rihanna; it channels the bittersweet joy of surrendering to the moment, in life and on the dancefloor, without discounting the incredible savvy it takes to stay on top. The layered production work from Boi-1da is a revelation, moving lightly from quietly intimate to deep and resonant. Drake here is a bit outmatched by RiRi, compared to their other duets, but he still gets the chance to pick her over her hypothetical twin. It’s a classic, navel-gazing Drake compliment, but also his most illogical—as “Work” proves, no one could ever be mistaken for Rihanna. –ESH

Listen:“Work” [ft. Drake]

Lists & Guides: The Grateful Dead: A Guide to Their Essential Live Songs

A User’s Guide to the Grateful Dead

By Jesse Jarnow

As avatars of San Francisco's ’60s-born counterculture, the Grateful Dead have served as an alternative to American reality for more than a half-century. Performing from 1965 to 1995 with guitarist and songwriter Jerry Garcia, the Dead survive through a vast body of live recordings, originally traded by obsessive fans and now preserved on a long string of official releases. Though the band has an epic narrative (told in Amir Bar-Lev’s rapturous four-hour Long, Strange Trip documentary), much of the Dead’s story and significance remains purely musical. Part of the group’s staying power is due to the mysterious vastness that exists outside the bounds of their official studio recordings, a live canon shaped by generations of the still-active Deadhead music trading network.

Flourishing in an extralegal sharing economy built around the exchange of concert tapes and psychedelics (the tapes were never to be sold), most of the Dead’s live recordings could only be accessed through profoundly anti-corporate means. Rather than killing music, as an infamous British music industry campaign claimed in ’80s, home taping actually propelled the Grateful Dead to stadiums, as the Dead themselves acknowledged.

Profoundly unslick, the Grateful Dead's anti-authoritarian creative tendencies remain palpable in the current era. Self-consciously apolitical and populist to a fault, the Dead built a diverse audience across the political spectrum while continuing to act as a catalyst for young and old seekers, music heads, counterculturalists, and psychonauts. Simultaneously, the Dead produced dancing music, folklore, and lyrics to nourish an extended community that continues to thrive at shows by the band’s surviving members and a national scene of cover bands.

Navigating the Grateful Dead’s shadow discography can be daunting, a tangle of different periods and idiosyncrasies. This list of recommended song versions—chronological, not ranked—serves as an introductory survey of the band’s different periods. Loosely, the 37 entries here chart a path from garage-prog (1966) to lysergic jam suites (1967-1969), alt-Americana (1970), barroom country & western (1971), space-jazz (1972-1975), and epic hippie disco (1976-1978), eventually arriving at the more slowly evolving band of the ’80s and ’90s, whose driving creative force sometimes seemed to be their own inertia.

It’s the latter era that is most prone to cleave even Dead enthusiasts. It represents a divide between the tighter, more critically accepted earlier band and the beloved-by-Deadheads ’80s and ’90s incarnations, when they were beset by addiction, the technologies of the era, questionable aesthetic choices, and an evolving secret musical language that sometimes made more sense in sold-out stadiums of dancing fans. While the Dead got more popular every year in their later decades—and continued to generate jam surprises and bold performances aplenty—new listeners will likely want to start with the band’s earlier epochs. One can see long-running debates even among our contributors encapsulated in entries for beloved songs like “Jack Straw” and the “Scarlet Begonias”/”Fire on the Mountain” combo, with a contingent of heads here deeply digging the chaotic stadium psychedelia of the later band.

The majority of the primary song choices presented below come from the classic years of the ’60s and ’70s; for many songs, Key Later Versions from the ’80s or ’90s highlight further developments for the discerning Dead freak. There, one can hear the band finding new places hidden in the old, mining the mountain range of material they'd generated earlier in their career.

Though the band’s proper albums have earned an undeserved bad reputation, American Beauty and Workingman's Dead (both released in 1970) especially contain a small handful of songs for which the studio versions remain almost undisputedly definitive. While songs like “Ripple,” “Attics of My Life,” “Box of Rain,” and several others belong on any list of the band’s campfire standards, they’re left off here in the interest of songs that varied more greatly in live performance. Likewise, Europe ’72, which features elements re-touched in the studio, generated a number of great live tunes served perfectly well the version found on that album, including “Ramble on Rose” and “Brown-Eyed Women.” Though the Dead continued introducing new originals up through their last tours, this list focuses on something like a core curriculum of live Dead.

Nearly every selection on this list can and should be argued by anyone with an opinion about live Dead recordings. But these picks are intended to be gateways into different scenic and well-manicured corners of Grateful Dead land for those who haven’t spent much time there, places that might feel welcoming before drumz/space kicks in. From there, the paths are nearly infinite: an enormous live catalog splattered unceremoniously across streaming services (but helpfully listed chronologically at DeadDiscs), the complete fan-curated collection at archive.org (navigable via DeadLists or Relisten.net), a riot of Grateful Dead historical and ahistorical blogs, academic conferences, a nightly slate of #couchtour webcasts, or a live music venue near you.

“You Don’t Have To Ask”

July 16, 1966

Fillmore Auditorium, San Francisco, Calif.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Grateful Dead

Overly complicated original is highlight of album’s worth of songs scrapped before debut LP. Played in 1966 only.

“You Don’t Have to Ask” has all the elements of a great garage band song. It’s got a groovy bass line, excellent reverby guitar solos, great group harmony vocals, and Ron “Pigpen” McKernan’s combo organ cuts right through everything. It’s a zippy little number, guaranteed to fulfill the Dead’s dance-band obligations. But while it’s catchy, it’s also totally fucking bananas. There are several verses, choruses, parts, sections, a bridge or maybe three, chords you don't expect (maybe they were surprised too), modulation up, (spoiler alert) modulation back down, then something else entirely, all at a breakneck speed for them and wrapped up in under four minutes. It kinda sounds like they (Bob) were still learning the song, but they're all really going for it, even if it was destined to be one of approximately an album's worth of originals dropped from the repertoire before the band signed to Warner Bros. in 1967. If there was a version of the Nuggets compilations that consisted entirely of songs written and played by lunatics totally zonked on acid, this would definitely make the cut. –James McNew

Lore: Deadhead forensics has determined that “You Don’t Have to Ask” was also known as “Otis on a Shakedown Cruise,” an early song title remembered by band members that seemingly didn’t survive on tape; at least until an attentive listener noticed that—seconds before this version starts—a band member can be heard off-mic asking, “Otis?”

Listen:Spotify | Apple Music

“Cream Puff War”

December 1, 1966

The Matrix, San Francisco, Calif.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Jerry Garcia

Included on the group’s debut LP, a rare original with both words and music by Jerry Garcia and early vehicle for exploratory modal jams.

It’s okay if you don’t like the Grateful Dead—even the Greatest American Band Ever isn’t for everybody. But if you’re an ardent Dead hater, I’d urge you to try just this one track. In a dimension where the Dead flamed out in obscurity, “Cream Puff War” would’ve justified their inevitable rediscovery by proto-punk collectors. Attacked with an urgency they’d never again employ, the song is on the garage-ier end of the psych spectrum, with a delinquent Farfisa and uncharacteristically fierce Garcia vocals. Of course, it’s still the Dead, so it’s a little too fussy for true garage-fuzz, with a pile of chords and sudden swerves into waltz time. Played only during the little-documented fall of 1966 and spring 1967, only a single extended version survives, the band consciously searching for new territory and exploring the modal improv mode they would soon make their own. Shelved soon thereafter, “Cream Puff War” remains an interesting thought experiment in Grateful Dead alternate history. –Rob Mitchum

Venue: The Matrix was a tiny San Francisco club co-owned by Jefferson Airplane’s Marty Balin, where the Dead played early shows and later experimented with side projects like Mickey and the Hartbeats. In some circles, it’s more famous for live recordings of the Dead’s fellow former Warlocks, the Velvet Underground.

Listen:Archive.org

“Viola Lee Blues”

February 2, 1968

Crystal Ballroom, Portland, Ore.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Noah Lewis (arr. the Grateful Dead)

The Dead’s first massive jam, a hopped-up jug band rearrangement built on three volcanic improv sections. A dependable mindbender and set centerpiece, whether as an opener or closer, “Viola Lee Blues” outlasted nearly everything else from the band’s 1966 playbook, but disappeared from live shows after 1970.

Legendary Dead tape collector and vault-master Dick Latvala coined the term “primal Dead” to describe the blustery psychedelia at the core of the band’s legend. And few early performances reveal the group’s unhinged nature as openly as this prison-blues chugger, written by Memphis singer/harmonica player Noah Lewis and originally recorded in 1928 by his trio, Gus Cannon’s Jug Stompers. Most Dead versions of “Viola Lee Blues” are a variant on its noisy appeal, including the rare excellent studio jam on the band’s 1967 Warner Bros. debut, yet what makes this show-opener special is power, precision, and compactness. The stand-alone opening chord is a universe. The sound of multiple vocalists screaming out the words betrays an on-stage good time rolling. Garcia’s mountainous arpeggios—using a deeply metallic guitar tone—are a study in Sturm und Drang naturalism; while the hanging pause on which the players reunite is big-band tightness exemplified. A perfect vehicle when secondary drummer Mickey Hart joined in 1967, here the closing jam’s leap into Kreutzmann/Hart-driven hyperspace is a premonition of future Rhys Chatham/Glenn Branca/Sonic Youth punk-jazz explosions. Strap the fuck in! –Piotr Orlov

Listen: Archive.org

Key Earlier Version: September 3, 1967, Rio Nido Dance Hall, Rio Nido, Calif. Recorded just before Mickey Hart joined the band, the Rio Nido “Viola Lee” is perhaps the best document of the early single-drummer Dead in full flight, with Garcia spinning out endless hypnotic turns.

“Alligator”

February 14, 1968

Carousel Ballroom, San Francisco, Calif.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, Phil Lesh, Robert Hunter

Non-performing lyricist Robert Hunter’s first contribution to a Dead song became a playful springboard. “Alligator” most often segued into “Caution (Do Not Stop on the Tracks),” a locomotive blues-fuzz groove almost wholly borrowed from Them’s “Mystic Eyes,” and in this infamous sequence into a blistering six minutes of guitar feedback.

Just before what sounds like a drum circle busts out, Bob Weir leans into the mic and says, “C’mon everybody! Get up and dance, it won’t ruin ya!” That bit of tape lifted later that year for the band’s pioneering studio/live hybrid, Anthem of the Sun. Weir’s got the earnestness of a prom chaperon gently chiding a wallflower. And why shouldn’t he? This was an era of raw fun for the Dead, prime Pigpen time, who hoots and hollers through his lead vocal, while Weir implores listeners to “burn down the Fillmore, gas the Avalon,” the two venues competing with the band-run Carousel Ballroom. Heavy competition. After the song relaxes from an early Kreutzmann/Hart drum sesh and the guitar finally returns, it’s sour but funky. Too good for even the shyest of the shy to not move their butts. –Matthew Schnipper

Listen: Spotify | Apple Music

Key Later Version: April 29, 1971, Fillmore East, New York City, N.Y. The final version of the song is a leaner reptile but with perhaps even more bite, the now-solo Kreutzmann drum segment chomping into a thrilling Lesh/Garcia jam.

“St. Stephen”

August 21, 1968

Fillmore West, San Francisco, Calif.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Jerry Garcia, Phil Lesh, and Robert Hunter

Cryptic lyrics, an elliptical psychedelic bounce, scorching guitar, occasionally a live cannon onstage, and always a Deadhead favorite.

For a few years in the late ’60s, “St. Stephen” anchored a suite that also included “Dark Star” and “The Eleven,” together taking up the first two sides of the pivotal Live/Dead double LP. Building sets around the rolling peaks of the suite, individually and together the songs showcased the band’s latest compositional ideas and quickly developing musical interplay. At the center was “St. Stephen.” Featuring some of Robert Hunter’s most lava-lamp-ready turns of phrase (“lady finger dipped in moonlight,” anyone?), ”St. Stephen” is alluringly simple: a bouncy psychedelic standby that may or may not have anything to do with the Christian martyr in its title.

At early performances, like this August take at the Fillmore West, it carries the energy of a band falling in love with their own sound, navigating the song’s left turns with aplomb. Bob and Jerry sing the verses together with childlike joy, before things slow down and get foggier, buoyed by spacey glockenspiel. Just a minute later, the whole band bounce back into action with a devilish energy, propelled by one of Jerry’s gnarliest riffs. The darkness shrugs, and the Dead ride on. –Sam Sodomsky

What To Listen For: The Live/Dead-era versions of the song end with several verses of a lysergic Irish-sounding jig, both a musical bridge and dramatic energy build before springing into “The Eleven” (with which it’s often erroneously tracked, as here).

Listen:Archive.org

Key Later Version: May 5, 1977 New Haven Coliseum, New Haven, Conn. Revived in slower, elegant form after the band’s 1976 return, “St. Stephen” attained a different kind of grace, sometimes still finding ecstasy (if not quite psychedelic fury) in the middle jam, as on standalone versions like this one, though more often segueing into Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away”.

“New Potato Caboose”

February 13, 1968

Carousel Ballroom, San Francisco, Calif.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Phil Lesh and Bobby Petersen

One of the band’s most structurally experimental songs sets a poem by band friend Bobby Petersen to music.

“It's a very long thing and it doesn't have a form,” Jerry Garcia told an interviewer about the Dead’s “New Potato Caboose” around the time the band started performing it in the late ’60s. The band had been writing original material since shortly after their 1965 formation, but “New Potato” was an indication of their rapidly expanding ambitions. Written by bassist Phil Lesh from a poem by Bobby Petersen, it highlights the former composition prodigy’s studied chops. What Garcia heard as formlessness, Lesh almost certainly designed—in his own hallucinogenic way—as specific movements, interconnected with an elusive dream logic.

Sung by Bob Weir with Lesh and Garcia joining for the cascading chorus, Weir sells its mystical (and maybe even proto-Sonic Youth) atmosphere with a stoney, detached edge during this Carousel Ballroom performance. Though they would never write another song remotely like it, “New Potato Caboose” foreshadows the territory they were about to conquer. –Sam Sodomsky

What To Listen For: On this classic early bootleg, a Deadhead staple sourced from an experimental radio broadcast on then-freeform KMPX, Garcia’s wild outro solo dissolves into Weir’s “Born Cross-Eyed” and a powerful articulated take of the piece of music Deadheads would label “Spanish Jam.”

Venue: Operated by a consortium of bands including the Dead, Jefferson Airplane, and Quicksilver Messenger Service, the Carousel Ballroom failed as a business, and was reopened as the Fillmore West by promoter Bill Graham.

Listen:Spotify | Apple Music

“The Eleven”

February 28, 1969

Fillmore West, San Francisco, Calf.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Phil Lesh and Robert Hunter

The band’s endlessly rehearsed double-drummer mindbender central to Live/Dead.

“The Eleven” is the Grateful Dead at their most joyous, all ascending scales, bursts of melody, shouted lyrics, and tricky meters designed to sound as if everything is on the verge of falling apart. Its essence is right there in the title: the song is in 11/8 time, meaning that three bars of 3/4 are punctuated with a quick 2/4 bash before the cycle starts again. The 11/8 frame turns out to be ideal for Garcia and Lesh, who solo in tandem on the best versions of the song. “The Eleven” was shorter, faster, and gnarlier in 1968, and the soloing—the best of which always happens before the brief verses begin—was more clipped. By the week in late February where they recorded the material that wound up on the epochal Live/Dead, Garcia and Lesh were working like two halves of the same musical mind. A Wednesday show at the Avalon Ballroom produced the Live/Dead version, but the Friday night show of that same week, one of four in a row at the Fillmore West, turned out to be the finest single moment for “The Eleven.” Garcia and Lesh are like two dogs barking and nipping at each other while running full-speed across a field, never breaking stride, taking turns being in front. Eventually, the tight three-chord structure would bore Garcia, who felt he’d wrung every idea he could out of the song. The Dead dropped it from setlists forever in 1970. But during this precise moment in February 1969 there are more ideas than they know what to do with. –Mark Richardson

What to Listen For: The overlapping three-part vocal is hard-to-sing overload, featuring some of Robert Hunter’s finest lysergic playfulness in Garcia’s trippy countdown part: “Eight-sided whispering hallelujah hatrack, seven-faced marble eye transitory dream doll…”

What Else to Listen For: The drums, man! Ideally on headphones.

Listen:Spotify | Apple Music

“Mountains of the Moon”

March 1, 1969

Fillmore West, San Francisco, Calif.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter

The Dead’s first and most psychedelic folk song has more in common with the Incredible String Band than Phish, used as a prelude to the jam centerpiece, “Dark Star.”

The peak old-folkie days of the Dead wouldn’t come until the early ’70s, but “Mountains of the Moon” was foreshadowed that era. Debuted in late ’68, the minimal ballad spent the first half of ’69 as the gentle prelude to its deeper astronomical partner, “Dark Star”; the last few notes of the February 27, 1969 version can be heard during the introductory fade-in to Live/Dead. On Aoxomoxoa, some heavy-handed harpsichord emphasizes the faux-Elizabethan melody and faerie-land lyrics, but live, a stripped-down lineup of Bobby on a 12-string, Garcia finger-picking, Lesh burbling, and Tom “T.C.” Constanten on organ made for a haunting lull in their primal phase. –Rob Mitchum

What to Listen For: Serving as a spell to put the band and audience in the ruminative frame of mind for the journey to come, Garcia essentially continues his closing “Mountains of the Moon” solo into the “Dark Star” intro, even while switching from acoustic to electric guitar.

Listen: Spotify | Apple Music

Watch: January 18, 1969 Playboy After Dark, Los Angeles, Calif. To see a possibly-dosed Hugh Hefner swaying along to “Mountains of the Moon” with his arm around a Bunny, check out the Dead’s surreal appearance on Playboy After Dark.

“Friend of the Devil”

May 2, 1970

Harpur College, Binghamton, N.Y.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Jerry Garcia, John Dawson, and Robert Hunter

Hail Satan!

1970 was a championship season for the devil. The Beatles broke up. Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin raised the curtains in the 27 Club. The Kent State massacres compounded the 6,173 body bags airlifted back from Vietnam. And the Grateful Dead unshackled “Friend of the Devil,” the best song ever written about a cuckolded bigamist fleeing from a sheriff’s posse and 20 hellhounds, only to get stuck up by Satan for his final $20.

Apologies to ’Pac and Snoop, but this is the most immortal outlaw anthem about attempting to return to your house out in the hills right next to Chino. Written by Robert Hunter with John Dawson of stoner C&W Dead spin-off New Riders of the Purple Sage with Garcia adding the bridge, the acoustic riffs ramble like an undiscovered escape route. Robert Hunter’s lyrics shine a searchlight on a Western anti-hero—Butch Cassidy bargaining with Lucifer—sleepless, ragged, and fatal. But Garcia sings with a weary sweetness on this staple acoustic set. A bouquet in hand, six-shooter behind his back; the poetic conman with insidious alliances, he seduces with his wounded decency, at least until he disappears into a cloud of sulfur. –Jeff Weiss

Listen: Spotify | Apple Music

Key Later Version: June 27, 1976 Auditorium Theater, Chicago, Ill. Following the band’s touring hiatus, Garcia was inspired to revive the song in a slower arrangement after hearing a recording of a live Loggins & Messina cover.

“Brokedown Palace”

August 30, 1970

KQED Studios, San Francisco, Calif.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter

Garcia and Hunter’s immortal farewell ballad and cosmic love song with Crosby, Stills & Nash-inspired harmonies.

The massive amount of high quality archival audio makes the Grateful Dead’s video output seem minuscule by comparison. Add crummy camerawork and dated psychedelic FX, and you often don’t have too much to look at. Not so for this simple and beautiful take of “Brokedown Palace” on local California TV, which keeps the fancy tech to a minimum. But on the chorus, marked by some of the Dead’s most beautiful earthy three-part harmonizing, Weir and Garcia’s profiles overlap on screen. It’s their own Mamas and Papas or Fleetwood Mac moment: two crooners, a heartthrob and a scruff, in total rhapsody. Sometimes, there seemed to be a disconnect between the band’s solemn sound and the way they made the audience feel. In 1970, the year Garcia and Hunter churned out two albums of instant hippie standards, it paid off, with the Dead in perfect harmony, both creatively and vocally. Everyone onstage and off is blissed out. How nice it is to share. –Matthew Schnipper

What to Listen For: Not shown on camera, the high part of the band’s three-part harmony is bassist Phil Lesh.

Listen: Archive.org

Key Later Version: May 11, 1977 St. Paul Civic Center, St. Paul, Minn. Like almost everything else in May 1977, “Brokedown Palace” sounded perfect, Donna Jean Godchaux’s harmony replacing Lesh’s, who mostly stopped singing in the late ‘70s after straining his vocal cords.

“Turn On Your Love Light”

September 19, 1970

Fillmore East, New York City, N.Y.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Joseph Scott and Deadric Malone

A frequent show closer from 1969-1972 and a showcase for Pigpen’s greasy raps and unfurling blues-psych boogies. From 1969-1971, especially, the Dead spent more time jamming “Love Light” than even “Dark Star,” playing it more often and usually for a longer duration as a populist get-the-heads-dancing rave-up to conclude their most far-out sets.

Defying the peak of primal Dead, the gutbucket blues of “Turn on Your Love Light” dominated set lists during the Dead’s most psychedelic era. Usually upwards of 20 minutes (and sometimes over 40), the band vamped between innuendo-filled raps by frontman Pigpen aimed at pairing off members of the audience. While conducting the band’s deft on-the-fly arrangements, Pig would spike the Bobby “Blue” Bland original’s sweetness into something more libidinal and fetishistic. “Well she’s got box back nitties/Great big noble thighs/Working undercover with her boar hog eye,” Pig sang, a bit of mojo jive that one scholar has spent ample time decoding.

By September 1970, the Summer of Love had given way to the Autumn of Fuck. Doing some crowd work, Pig whips the audience into a frenzy, perhaps creating the sort of “weird atmosphere” that led one feminist reviewer to feel alienated by the“hippie stag party” later that fall. After the band strikes the final beat, Pigpen screams “Fuck!”—issued as both punctuation and command. This “Love Light” scores 5 fucks—one for each time the word is uttered by the band. –Ariella Stok

Listen: Archive.org

Watch: August 16, 1969 Max Yasgur’s Farm, Bethel, N.Y. At Woodstock, as the Dead begin a 36 minute “Love Light”, a still-unidentified rando takes over the mic, soon led away when Merry Prankster Ken Babbs distracts him with a joint.

“Dark Star”

April 8, 1972

Wembley Pool, London, UK

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Grateful Dead and Robert Hunter

The band’s definitive psychedelic jam epic, with wondrous versions in nearly every era it appeared.

In April of 1972, the Dead commenced a major European tour, almost two months long and a definitive musical turning point. Elongated fast ’n’ furious blues jams and Wild West saloon swagger were dosed with jazzier, subtler improvisations, the Dead’s musical shorthand cribbed from the simultaneous soloing of Dixieland music. Introduced to listeners via a short and far-out 7" in early 1968 and the standard side-long take of Live/Dead in 1969, the April 8th, 1972 version is not a “Dark Star” of gaping existential canyons jagged with feedback. The exuberance of the band listening to itself in this half-hour house of mirrors can be heard as Garcia’s Alligator Stratocaster quickly descends from the song’s head, Lesh offering bubbly harmonic counterpoint; accents of cymbals and short drum rolls make Weir’s offbeat rhythmic attacks more potent and clear space for Keith Godchaux to pound out leads on his piano. A collective breath is taken after the first and only verse, until Kreutzmann’s kick drum cajoles the rest of the Dead, including Pigpen behind the organ, to percolate a melody, pause for a brief freak-out, and wrap up the song with sunburst triumph. –Buzz Poole

What to Listen For: The charging major key jam that erupts near the end of this version also features a fiery debate about what will follow, eventually sliding perfectly into Weir’s “Sugar Magnolia” and a version of Pigpen’s “Caution (Do Not Stop on the Tracks)” filled with crackling heat lightning.

Listen:Spotify | Apple Music

Key Later Version: October 31, 1991 Oakland Coliseum, Oakland, Calif.At the unexpected and emotionally charged five-show wake for promoter Bill Graham, the Dead’s staunchest supporter, “Dark Star” became a time machine when novelist Ken Kesey delivered a Halloween eulogy and the band flashed back to the Acid Tests, eight musicians so locked in that you can imagine walking between all the notes.

Dark Star Canon (Excerpt):

2/28/69 Fillmore West, San Francisco, CA [Live/Dead, dude.]

2/13/70 Fillmore East, New York City, NY [Taper favorite.]

8/27/72 Old Renaissance Fairgrounds, Veneta, OR [Transdimensional meltdown.]

10/28/72 Cleveland Public Hall, Cleveland, OH [Hyperreal, with so-called bass-led Philo Stomp.]

10/26/89 Miami Arena, Miami, FL [MIDI tour-de-force with bummer Garcia vocals.]

“The Other One”

April 26, 1972

Jahrhunderthalle, Frankfurt, West Germany

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Bob Weir and Bill Kreutzmann

A high-wire version of one of the band’s premier jam vehicles in nearly every era. After dropping “Cryptical Envelopment” in 1971 (minus a brief ’80s revival), “The Other One” became the jam center of many second sets, its triplet-based gallop providing a tension-laden motif for high energy improvisation, perfect for segues, creating a jam canon second only to “Dark Star”.

Released in 1995 as Hundred Year Hall, the Grateful Dead’s April 26, 1972, show in Frankfurt is a tour de force display of pretty much everything the Dead were capable of at this juncture, from earthy Pigpen-led R&B to country-fried workouts to daring improvisation. The latter is best exemplified by the sprawling, 36-minute wonder that is this night's reading of “The Other One.” Originally bookended by Jerry Garcia’s “Cryptical Envelopment,” by 1972 the song had been both pared down and expanded, providing the Dead with a vehicle for their most untethered—and sometimes most aggressive—jams. Coming out of a rollicking “Truckin,’” the Frankfurt “Other One” bursts into action with Bill Kreutzmann's relentless “tiger paws” rhythm and Phil Lesh's rumbling bass, leading directly into a kaleidoscopic roller coaster ride. Jerry Garcia darts madly around with fleet-fingered, often feedback- and wah-drenched guitar work as pianist Keith Godchaux pounds out Cecil Taylor-isms. Even the usually jam-averse Pigpen gets into the act with a stabbing organ part. Before the Dead finally slip into a gorgeous “Comes a Time,” Bob Weir bellows the now-famed lyrics about their deceased mentor, Beat icon Neal Cassady—and there's no question that his gonzo spirit was at the wheel during this performance. –Tyler Wilcox

Listen: Spotify | Apple Music

Key Earlier Version: February 27, 1969 Fillmore West, San Francisco, Calif. Sounding fairly goofed up as they introduce the last portion of the evening’s early set, the band dazzles with a complete version of the “That’s It For the Other One” suite, with Garcia’s spiraling “Cryptical Envelopment” intro and outro.

Key Later Version:February 5, 1978 UniDome, Cedar Falls, Iowa. A reliable source of headiness for much of the Dead's career, “The Other One” was especially good in the late ’70s, as on this explosive 1978 rendition.

“China Cat Sunflower” > “I Know You Rider”

August 27, 1972

Old Renaissance Fairgrounds, Veneta, Ore.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter/traditional, arranged by Grateful Dead

Grateful Dead-brand sunshine in a can links baroque psychedelia to a folk song the Dead arguably made an American classic. During the ’70s, “China > Rider” was a first-set standard, usually the place where the band would initialize their improvisational chops on any given night. In the ’80s and ’90s, it moved to the second set opener slot, a guaranteed crowd favorite to settle fans back in.

To get the absolute purest dose of what the Dead sounded like, lick your finger and stick it in the middle of any rendition of this classic pairing. For one, the duo nicely charts the main axis of Dead songwriting, with effervescent psychedelia blending into an electrified rearrangement of a traditional American folk song. But more important is the zone between the two songs, so humbly notated with a “>”, where the magic truly blooms. For several glorious minutes, the band exists in a quantum state between the two compositions, navigating that space with an uncanny group-mind. In August of 1972, the Dead played a benefit in sweltering heat for the Kesey family creamery outside Eugene, Oregon. Like most things with the Grateful Dead, what should be a calamity is instead transcendent, with “China > Rider” (the “>” is silent) one of several sublime performances. –Rob Mitchum

Listen: Spotify | Apple Music

Key Slightly Later Version: June 26, 1974 Providence Civic Center, Providence, R.I. In 1973 and 1974, the “China > Rider” transition included a theme based on Simon & Garfunkel’s “Feelin’ Groovy”, and this version includes both a rare intro jam and a turn through the descending melody that Deadheads call “Mind Left Body,” after its resemblance to a Paul Kantner song.

“Bird Song”

August 27, 1972

Old Renaissance Fairgrounds, Veneta, Ore.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter

A fragile goodbye doubles as a perfectly titled lift-off for some of the band’s most lilting and delicate jams.

Janis Joplin, the Grateful Dead's friend and occasional tour mate (not to mention Ron “Pigpen” McKernan’s on-again-off-again lover), died of an accidental heroin overdose in October 1970 at the age of 27. A few months later, the Dead unveiled “Bird Song,” Robert Hunter and Jerry Garcia’s touching farewell tribute to the singer. Not so much an elegy as a reminder to—as one of Joplin’s signature tunes puts it—get it while you can, “Bird Song”’s studio incarnation appeared on Garcia’s first self-titled solo LP. But the song really took flight onstage with the Dead in 1972, especially during a show at Veneta, Oregon’s Renaissance Fairgrounds, legendary among tape traders for decades before being officially released in 2013. Following a bittersweet, gently psychedelic verse and chorus, the band slides into a long, meditative modal jam, Garcia’s guitar sounding simultaneously mournful and ecstatic as it soars into the upper register, his cohorts circling patiently below. Bill Kreutzmann, handling drumming duties alone, gives the song a restless, jazzy lope. A sublime ensemble performance, made only slightly less sublime in the Sunshine Daydream concert doc, which features an undulating, naked fan perched directly behind Garcia, getting the sunburn of his life. –Tyler Wilcox

What to Listen For: The way Kreutzmann launches the band back into the jam with a fluttering drum fill.

Listen: Spotify | Apple Music

Key Later Version: October 1980 Radio City Music Hall, New York City, N.Y. The Dead introduced an unplugged—but no less exploratory—“Bird Song” in 1980, a high-flying highlight of the band’s Reckoning live LP.

“Playing in the Band”

November 18, 1972

Hofheinz Pavilion, Houston, Tex.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Bob Weir and Robert Hunter

The Dead’s archetypal meta-anthem, with every version from 1972 through 1974 diving into deep, heady, and swinging space-jazz. Part of Bob Weir’s first major batch of original songwriting and included with an abnormally good studio jam on 1972’s Ace, “Playing in the Band” was played as a standalone first set closer in the early ’70s, migrating to the second half of the show in later years where it was often split apart by one or several songs inserted between the song’s beginning and final chorus.

1972 was the year of “Playing in the Band,” played more often than any other song and site of some of the band’s deepest explorations. Bob Weir swaggers his way through the meta lyrics of the three-minute pop form, which then melts on a downbeat directly into the outer reaches of a jam that comes as close as the Dead ever achieved to what jazzheads refer to as fire music. Swelling insistently through several movements, the rhythm section pilots—Billy Kreutzmann approaching Elvin Jones-like intensity and Phil Lesh constructing architectural leads only to explode them with double-stopped, low-frequency bass bombs. Interlaced throughout, Garcia’s strobing guitar creates a zoetrope-like effect of white-hot intensity. When it’s time for re-entry, Donna Jean Godchaux wails as though birthing the chorus’s reprise from her very loins, and one is overtaken in ecstasy by the feeling of having emerged triumphant following a journey into the unknown. –Ariella Stok

Listen: Archive.org

Key Later Version: November 6, 1979, The Spectrum, Philadelphia, Pa. Keyboardist Brent Mydland had joined the band earlier that year and already his deep rapport with Garcia is on display, while the arrival of new synths provides a whole new sonic space-time-continuum for this “Playing” to tear asunder.

Jam

July 27, 1973

Watkins Glen Motor Speedway, Watkins Glen, N.Y.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Grateful Dead

Well, duh. But not as duh as you maybe think.

Oh, of course the Dead almost always jammed, but it was less often that they produced a piece of improvisation from a standing start. It certainly happened occasionally, but never in front of a larger audience than at the Watkins Glen Motor Speedway in July 1973, which itself held the title of largest concert in rock history until Rock in Rio unseated it in 2001. Sharing a bill with the Band and the Allman Brothers in front of an estimated 500,000 people, the three groups played unannounced public warm-ups in front of the assembling crowd the day before the ticketed event, with the Dead deciding (naturally) to play two warm-up sets. One second they’re tuning, and then a cymbal swell drops them into a fluid musical conversation that hints at songs they haven’t even written yet. Mostly it’s just an easy-going dialog between the quintet where one can hear the the chillest iteration of the band’s single-drummer 1971-1973 peak, Bill Kreutzmann’s free dance holding together star-splatter by Garcia, Lesh, and the gang. –Jesse Jarnow

Listen: Spotify | Apple Music

Key Avant-Dead Jam: September 11, 1974 Alexandra Palace, London, UK. A number of 1974 performances featured duet performances by Phil Lesh and proto-noise piece Seastones composer Ned Lagin, some of which segued from Lagin’s “moment forms” into the Dead’s set as the band joined in, including this magical improvisation from London’s Alexandra Palace that flows from modular synth eruptions towards the friendly skies of “Eyes of the World.”

Key Later Version: October 26, 1989 Miami Arena, Miami, Fla. By the ’80s, the Dead’s free jamming mostly isolated itself in the guise of their second set “Drumz/Space” segments, the primary forum for the band’s remaining avant-garde leanings and musique concrete-like MIDI explorations, as on this post-“Dark Star” exploration from 1989.

“Weather Report Suite: Prelude/Part 1/Part 2: Let It Grow”

November 21, 1973

Denver Coliseum, Denver, Colo.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Bob Weir/Bob Weir and Eric Anderson/Bob Weir and John Perry Barlow

Perhaps Bob Weir’s most ambitious composition, sad autumnal folk bursts open into elemental Garcia leads. Played 46 times in 1973 and 1974, Weir dropped the gentler first two segments of the piece when they returned in 1976 with second drummer Mickey Hart, though “Let It Grow” remained consistently in rotation through the remainder of the band’s career, a late first set home for improv.

First played as a complete piece in September of 1973, Bob Weir’s “Weather Report Suite” was a coming of age for the band’s rhythm guitarist and youngest member. First fiddling with the baroque chords of the “Prelude” during earlier jams, the full composition was perhaps Weir’s earthy answer to Jerry Garcia’s “Eyes of the World” for the Wake of the Flood era. In Denver on November 21, 1973, the “Suite” is both fragile and reassuring to start, each instrument falling into place. With subtle interplay between Lesh’s unique lead bass, Garcia’s shimmering slide, and Keith Godchaux’s Fender Rhodes setting up a call and three-part-harmony response, it all moves towards the breaking storm of “Let It Grow.” There, Kreutzmann’s light and lean drums lead tempo shifts in a dynamic and subtle jazz jam, opening up to the wild beyond. –Cori Taratoot

Listen: Spotify | Apple Music

Key Later Version: June 24, 1985 River Bend Music Theater, Cincinnati, Ohio. The entire band launches full-throttle into a furious, tight and edgy version, with Garcia finding raging solos in every open space.

“Here Comes Sunshine”

December 19, 1973

Curtis Hixon Convention Hall, Tampa, Fla.

Listen on Apple MusicWritten by: Jerry Garcia and Robert Hunter

Gang harmonies and bright syncopation made for a song whose original incarnation lasted barely a year. Inspired by Abbey Road-era Beatles, “Here Comes Sunshine” was one of over a half-dozen Garcia/Hunter songs debuted February 8, 1973 at Stanford University, some (but not all) destined for that year’s self-released Wake of the Flood.