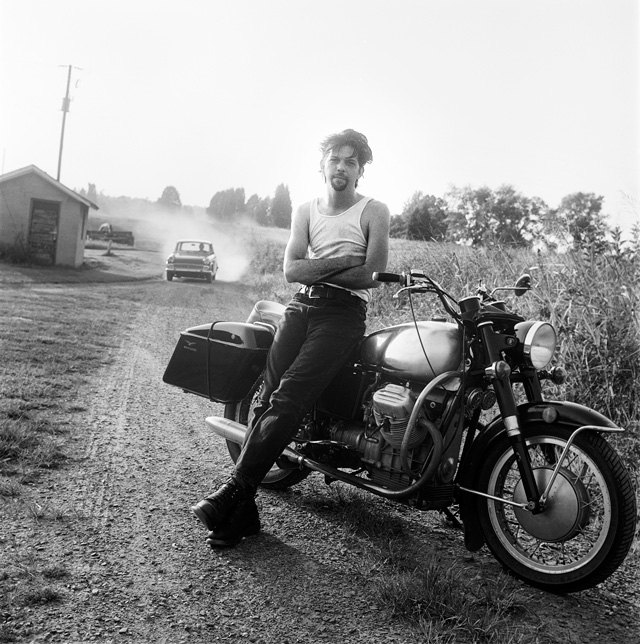

5-10-15-20 features people talking about the music that made an impact on them throughout their lives, five years at a time. In this edition, we spoke with 70-year-old actor, writer, comedy icon, bluegrass musician, and American Banjo Museum Hall of Fame inductee Steve Martin. His new collaborative album with Edie Brickell, So Familiar, is out October 30 on Rounder Records.

“The Great Foodini” Theme Song

It was a kids’ TV show, but I also had a record of the theme. They sang this song: “Oh there’s nothing he can’t do/ He’s the one and only Foo-DINI.” I listened to it a million times. It was my introduction to music.

Chuck Berry: “School Day”

In 1954 or ’55, the world was transitioning away from songs like “Old Cape Cod” and “How Much Is That Doggy In the Window?”—music that was very much rooted in the ’40s. Then, all of a sudden, there was this explosion: When I heard “School Days” by Chuck Berry I thought a miracle had happened. As a 12-year-old, the lyrics perfectly described what was going on in my life: “Up in the morning and out to school/ The teacher’s teaching the Golden Rule/ American History and classical math/ You study ‘em hard, hoping to pass/ Working your fingers right down to the bone/ The guy behind you won’t leave you alone.” It was very hard to find this music in Orange County, California around that time, and the only way we could get it was by listening to this AM radio station from San Diego late at night. I used to fall asleep listening to the music.

I also started working at Disneyland at age 10, which was legal back then.

Flatt & Scruggs: Foggy Mountain Banjo

I really enjoyed working at Disneyland, and by the time I matured to age 15, I was working there until 2 a.m. doing magic. My introduction to bluegrass was really through my friend John McEuen and, on record, through the Dillards and Flatt & Scruggs—but for live music, at that age, [Disney’s house bluegrass band] the Mad Mountain Ramblers were the only nearby bluegrass band. This girl I worked with at the magic shop always wanted to take long breaks to see her boyfriend, and I wanted to take long breaks to see the Mad Mountain Ramblers, so we made a deal: Don’t tell anybody. [laughs]

The Mad Mountain Ramblers did not do comedy, but the Dillards certainly did and they were fantastic at it. You would be laughing your head off, then they would start a song going at 90 miles an hour. It was thrilling to see. But comedy was not an essential part of the banjo for me; Flatt & Scruggs never did comedy and they were my heroes too.

When I got interested in the banjo, I just went to a record store and found Flatt & Scruggs’ Foggy Mountain Banjo; when you’re interested in an instrument as aggressively as I was, you do everything you can to find out about it. Orange County was a big home for folk music back then, and a lot of clubs and coffee houses sprung up. There were so many varieties of music being played on banjo at the time, including folk and bluegrass, which are two different things. Folk is very Kingston Trio and strumming the banjo, while bluegrass music is picking the banjo. And then I got into clawhammer banjo, which is more American and English—Appalachian, we call it, but the Appalachian music really came over from the British Isles.

When I was 20, my friend John McEuen and I drove down to La Jolla, California, and met Earl Scruggs. He was very generous and taught me how to play “Sally Goodin’” his way—in fact, there’s a recording of me playing that song on the back of the “King Tut” 7”.

I shifted into college and got very interested in classical guitar, especially Spanish classical guitar. I don’t mean flamenco. It was by the composers: Joaquín Rodrigo, Heitor Villa-Lobos, and especially Andrés Segovia. I was in a philosophy class once, and everybody had to describe something aesthetic. The smartest guy in class described listening to Segovia. He said—remember, this is a philosophy class—“It’s like the perfect circle floated into the room.” And that’s what it was: beautiful, perfect, emotional music. I think that guy got an A for the course.

Even though it was the mid-'60s, I really didn’t find the Beatles for a couple of years because I was busy listening to classical music, which I loved—Bach, Händel, and others. I listened to them over and over and I’m really glad I did, because they influenced the structure of my music today.

Then I became a writer on the “Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour” and we had all these groups on the show like the Doors, the Who, and the Beatles. Being there when George Harrison came into the room, you understood the excitement of those screaming girls—these guys changed the world, and when you were in the presence of one of them it was an eerie feeling.

I love Joni Mitchell, especially during that period in the early ’70s. But I never met her—it was always a near miss. She lived in Laurel Canyon; I lived in Laurel Canyon. As a comedian, I was a little bit of an outsider to the music scene. I was friendly with Glenn Frey from the Eagles and I worked at the Troubadour, where everybody worked. Linda Ronstadt played there—we had a few dates actually, Linda Ronstadt and I. She was a very street smart person and a really good talker. But I didn’t meet Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young or Joni Mitchell, whom I would have loved to meet. And I’m sorry that she’s having health issues now.

Celtic Music

Nineteen seventy-five would be very much the beginning of the Celtic rush for me. It wasn’t as easy to listen to music if you were on the road, which is where I was—there was no way to listen to it except the radio. We had cassette players, so I could make mix tapes [laughs], but it was a very elaborate process to make a cassette back then. I’d mix it up a lot between classical guitar, bluegrass, and Celtic.

That year, Buckingham Nicks and I both found ourselves at this tiny club in Greenwich Village, where everything was happening. I didn’t know who they were, they didn’t know who I was. I think they were opening for me. The first night there was nobody there. I was making $300 a week, which seemed like a fortune, and I said to the owner, “Look, I don’t expect to get paid if no one comes in.” And he said, “No, no, it’s going good.” Then nobody came again on the second night, and I said, “Look, let’s stop.” And he said, “OK.” And I left. You can’t play to nobody, although I’ve done it before.

The Bothy Band: “Maid of Coolmore”

I was touring as a comedian, which is very isolated and lonely. I loved the dark poetry of Celtic music—especially the Bothy Band and the Chieftains. The Bothy Band’s “The Maid of Coolmore” affected the writing of the screenplay I did called L.A. Story—if you look at the lyrics to the Bothy Band song and the story of L.A. Story, it’s identical.

I was also very interested in '30s music around that time because I did the movie Pennies From Heaven. I thought the BBC series [from which the movie was adapted] was absolutely fantastic and very moving—just the kind of emotional project I needed after 18 years of doing standup comedy. At that point, I still owed the record company [Warner Bros.] another comedy album but I really didn’t have enough material; I was pulling out of standup, so I only had enough for half a side. Nobody was interested in Steve Martin banjo music, but we had these songs that we recorded nine years earlier, so we put them on the B-side of [1981 album The Steve Martin Brothers]. It was a little bit of a cheat on my part.

I was shooting The Three Amigos and I got tinnitus. I blamed it on gunfire at the time but since then I realized it was just my destiny after listening to music too loud my whole life and playing live concerts with 28,000 screaming people—it was like being in a football stadium. Tinnitus becomes easier to live with. It becomes your natural background noise.

Enya: “Angeles”

The early-'90s was a time when I was very introspective. I liked the blank quality of new age music, though some is better than others. It gave me a chance to lie down and think; it’s truly the background music to your mind. It was enjoyable for a while, but then I got out of that period.

Enya actually wrote a tune called “Angeles” for L.A. Story, though we ended up using two or three pre-existing songs of hers in the movie and she released that song later. Looking back, it’s the perfect music for that movie, and for that era too.

I did not listen to music around this time. I was short on devices; it was a transitional period. I did have CDs, but I was traveling and I don’t have a real recollection of what kind of music I listened to.

I picked up the banjo again when I was about 55. There was a fantastic period of the revitalization of music. This software program, I think it was called Netscape? Napster! It revitalized my music listening. I could search for oldies, bluegrass, anything—and find it. I think it actually helped music sales at first, because I would then go out and buy the CD. And then I realized—and everybody else realized—it was illegal. [laughs]

At some point, all the bluegrass radio stations died out or weren’t available in L.A.—it wasn’t like it is today where you can call up any radio station in the world. But then I got Sirius radio, which deeply affected my re-entry into bluegrass: I could hear contemporary artists and I really admired the way they were playing. I thought, “That’s exactly what I want to sound like.” And then I discovered some other artists who would send me their CDs and I loved them. There was a couple of really significant CDs that dropped into my lap by Tony Ellis and Mark Johnson, both clawhammer banjo players.

In 1965, if Earl Scruggs’ quality of banjo playing was at 10, the quality for the average player was more like five. But when I came back into the bluegrass world in 2000, I realized that the quality of the average player was closer to eight: The whole genre had risen to another level of excellence, and bluegrass musicians were playing at the level of high-quality classical musicians. Yet it’s still hard to earn a living: These fantastic players were still working and trying to pay off their banjos.

I talked to my wife and we both established this fund, [The Steve Martin Prize for Excellence in Banjo and Bluegrass], which would just give people money, essentially. It was a way to bring attention to the player and the music in general and help people out. Noam Pikelny, the first winner, was and still is an innovative player, but he also played the old way. He could play any style, and he’s a very charming guy in person. He has a great wit.

I don’t know how I listen to music anymore. I used to have it on my iPod and my computer, then everything changed to streaming and all my playlists vanished. It was like starting over.

But I’ll still put on the bluegrass channel. And my wife is much hipper about music than I am, so I coincidentally hear a lot of music that she plays that’s more contemporary in that sort of Americana world. I can’t really tell you the names. I don’t really ask. I like Mumford & Sons but I’m not really keeping up with it. I’m really very busy.