Ash Koosha: "Harbour" (via SoundCloud)

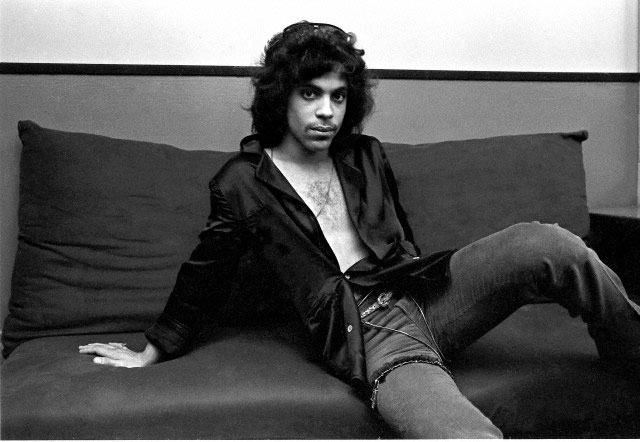

As first gigs go, it could have gone worse. Burgeoning rock group Font had never played in public before, but lead guitarist Ashkan Kooshanejad and his bandmates still managed to draw a crowd of 600 to a private suburban villa. Then again, it could have gone a lot better, too: As their set ended, the band heard audience members screaming—not in approval—and caught sight of police officers coming over the villa's walls on ropes, ninja-style. A helicopter hovered overhead.

It sounds like something out of an ‘80s action movie, but no; this was Iran in 2007, and concerts featuring rock music and a mixed audience were strictly forbidden. More than 200 people were arrested that night, and Kooshanejad and the rest of his band were sentenced to three weeks in jail. "Usually when you get arrested in Iran you go to jail for one night and your parents come to take you out and it's fine," he says. “But this was crazy.”

Not long after that first fateful concert, though, Kooshanejad and his friend Negar Shaghaghi were already at work on a new project, the electro-pop-leaning Take It Easy Hospital. In what seems now like an equally fateful series of events, Manchester's In the City Festival invited the pair to play, and around the same time, the Kurdish Iranian director Bahman Ghobadi invited Kooshanejad and Shaghaghi to collaborate with him on a film about Iran's underground music scene, loosely based on their own experiences.

The film, No One Knows About Persian Cats, ended up winning the Un Certain Regard Special Jury Prize at Cannes. But not long after that, as a wave of protests following Iran’s 2009 elections swept the country, the authorities once again began cracking down on musicians and young people at home. Take It Easy Hospital’s drummer was arrested and beaten, and an Iranian-American co-writer of the film, Roxana Saberi, was charged with espionage and sentenced to an eight-year prison term (that was later overturned). Kooshanejad and Shaghaghi decided to remain in the UK, where they eventually received asylum.

Given all this turmoil, one might expect Kooshanejad, like so many exiles before him, to be making protest music. Instead, he's delving excitedly into technologies that test the limits of representation itself. He began experimenting with electronic music when he was still studying classical composition at the Tehran Conservatory of Music, dropping samples into Cool Edit Pro, a rudimentary piece of sound-editing software; five years ago, he began working with Logic and resumed his experiments. He was drawn to samples for their real-world qualities, he says, because they seemed to capture something essential about life and the world. And that, in turn, opened up a curious acoustic rabbit-hole.

"I was reading a lot about quantum physics and nanotechnology—particles and matter, basically," he says. "And I started to treat sounds as physical objects." He began to imagine his sound-objects under electron microscopes, and the jagged landscapes they might yield. "It opens up a whole other geometry that we don't see normally," he says. Those shapes became the models for his new compositions.

Today, the 30-year-old producer lives in London, where he records mind-bending electronic music as Ash Koosha. From listening to his debut album, GUUD, recently released on Olde English Spelling Bee, you wouldn't guess that he had a past as a rebel rocker—much less as a student of Persian classical music. The opening song's lurching beats and beatific vocals suggest the influence of Flying Lotus, but the album quickly turns idiosyncratic, full of granulated tones and dissolving rhythms. Its closest point of comparison might be Gobby or Arca, electronic musicians with a similarly deconstructive—or maybe just plain destructive—approach to genre and the fabric of sound. It's heady music, and on tracks like the stumbling "Bo Bo Bones", it can be tough to detect any kind of solid form at all beneath the chaos.

Interestingly, Kooshanejad mostly listened to classical music while recording GUUD—Vivaldi, Wagner, and Chopin. Vivaldi's Winter, in particular, influenced his thinking. "It was like I was composing classical music, but there were no violins, no piano, no brass—just weird, unknown sounds that I can't put a name to. But it's still the classical structure."

As a composer, Kooshanejad thinks on a grand scale. One of his next projects is to transform the first 12 minutes of GUUD into a virtual-reality experience for the Oculus Rift headset. "I had this idea to turn electronic music albums into more accessible forms, with visuals," he says. "Imagine if you buy an album, put the Oculus Rift on, and go inside the album—and the sounds move around you. I've tried it out a few times, and believe me, it's amazing."

Pitchfork: Do you foresee going back to live in Tehran at any point?

Ashkan Kooshanejad: I miss that country, but I wouldn't want to stay in any place for longer than 10 years, honestly. It's good to travel and see what's happening in the world. As an artist, environment has a lot of impact on choices, and these choices can change by changing your location.

Pitchfork: Do you know where you'd go after London?

AK: Probably New York because I've never been to America.

Pitchfork: When you began making electronic music did you have any inspirations for what you wanted to do?

AK: I didn’t have any idea about electronic musicians. [laughs] I knew something about Aphex Twin, but I didn’t know what the name was. I was just listening to random CDs that people gave me. And I heard some Mogwai at some point, Portishead, Massive Attack. But I found out about the names about five years after that.

Pitchfork: When you studied at Tehran's conservatory, did you have access to electronic or electro-acoustic music?

AK: Not really. We didn’t learn much about computer music. But we had a lot of things going on with the physical side of sound. So that's when I thought, “Maybe I should work with frequency more, rather than just playing the cello or piano.” I wanted to explore sound, rather than composition and form.

Pitchfork: You've said that you treat samples as though they are physical objects. What does that mean?

AK: I stretch them like objects to see what’s happening, which opens up a whole other world of sound. So then I thought to myself, “OK, I have these objects, I have to make something out of them.” So I tried to use my classical compositional knowledge to give them some sort of musical meaning.

Pitchfork: So you're zooming in on the waveform, and then structuring the composition according to its contours?

AK: Exactly. I use a lot of visual software that gives you the ability to see sound when you zoom in. It's like I have these abstract band members in a Logic project, and they come together as a harmony. I’m only the conductor. I’m just telling them where to stand.

Pitchfork: Are you using any elements of Persian classical music?

AK: In some parts I used a lot of the groove from the south of Iran, and "Harbour" is my attempt to make southern Iranian music. The name translates to Bandar, which is what they call the "harbor music" of southern Iran.

Pitchfork: I understand that you recently wrote and directed a film.

AK: Yeah, I did. It was my first attempt. I wrote the story with Negar, and my brother is the cinematographer and producer. It's called Fermata. It's a classical musical term—a grand pause, basically, where the conductor holds the note for a long time. The film is about a guy who is about to die, and his brain is on a grand pause—on hold. So the whole film is showing that grand pause, where he's thinking about life and death. He's asking questions, seeing people from the past. It's in black and white and shot with £12,000, which was a great experience for managing funds.

Pitchfork: It seems like you're interested in bringing a wide range of media together in your work.

AK: At some point in my life I thought it was good to specialize, but now I think it’s good to build a bigger product than just music.