Practically an unknown quantity at the start of the decade, K-pop is now a household name around the globe. In recent years, the Western media has all but overflowed with a rising tide of South Korean pop, from fashion spreads to viral ads, Lorde pull-quotes to Grimes tweets, music video analyses to industry think pieces (and, of course, the most popular piece of content on the internet). And yet, so little of this attention has paid much mind to the music itself. If K-pop seems like the fad that never ends, that’s probably because it never really started, either.

K-pop treats a song as just one of several interlocking aesthetic parts, which typically include corresponding choreography, a music video, novella-thick liner notes, the occasional corporate tie-in, and an overarching “concept” that brings it all together. These tend to be conceived in tandem to a much greater extent than in Western pop, so to divorce a K-pop single from its context is to engage with it only partially. For example, the absurdist satire of “Gangnam Style” wouldn’t make total sense even to someone living in Gangnam without its attendant video and “horse dance.”

At its best, K-pop’s package-product approach can result in concise, nonpareil pop music gesamtkunstwerks—but good or bad, they can cause sensory overload for the uninitiated. The intense rate of productivity in Korea, where taking even a year’s pause between albums can kill a career, also adds to the overwhelming feeling for casual fans and popstars alike; onstage fainting and use of IV drips for energy are commonplace.

Another factor is the highly micromanaged way in which all these complementary pieces are made and aligned. The Western media loves to fixate on K-pop’s “assembly line” methodology, and the industry’s de rigeur trainee development program indeed prizes performative excellence over any kind of creative aptitude. Considering the cost-intensive multimedia project that is the typical K-pop smash, it’s little surprise that agencies tailor these acts and their images to best court audiences that are most likely to reward their investment: obsessive teenyboppers. As such, both the presentation of the music and the “impersonal” way it’s made fundamentally disagree with most Western music fans’ Beatles-derived notions of authenticity. (The language barrier can be a roadblock as well.)

But the Korean music industry—for all its bright color schemes, plastic sheen, and frankly commercial raison d'être—has quietly produced some of the most intelligent, adventurous, and accomplished mainstream pop of the past few years. It’s a world where songs with whiplash tempo cuts, Punjabi-via-Korean lyrics, and irregular beats exist as hyper-realized pop commodities, but connect with audiences on a mass scale. The following list offers a modest introduction to the hugely saleable genius some of the world’s best songwriters, producers, and performers can achieve when working in close cooperation.

Simply put, f(x) is the most reliably risk-taking act in K-pop. Created in 2009 by SM Entertainment, the multinational, five-piece girl group’s two albums from the past year mark an unmatched winning streak in a mainstream market more inclined toward singles and mini-albums (K-Pop’s clever rebrand of the EP). “Shadow” is one of the stranger highlights from 2013’s neon Pink Tape. Built around a jazzy discord of flats and sevenths, the song’s synth harmony and xylophone melodies have more in common with a Thelonious Monk rag than anything on most modern pop charts (it peaked at #6 on Korea’s national chart, despite not being an official single). Exacerbating the tonal wooze is a pitch-shifted sample of what might as well be a gaggle of fairies getting fumigated. Above it all, the girls of f(x) detail a dark diary of stalking an object of desire. The fraught confessional is set to an R&B melody that’s lullaby-sweet, seeming to temper the tension in the arrangement—until the lyrics register.

As the youngest member of the quartet Brown Eyed Girls, Ga-In uses her solo career to test the limits of both Korea’s mainstream music and morals. “Tinkerbell”, a coy invite to a midnight tryst, is introduced by a damaged, half-deleted Latin guitar and proceeds to synthesize wobbly LFO chords, compression-blown riffs that could deafen Sleigh Bells, violent jump cuts to millisecond silence, yawps like a young Karen O’s, surf rock guitar leads, a lone bebop trumpet interjection, severe glitch undertones, and a four-bar break that snaps off-grid altogether. The song opens Ga-In’s excellent Talk About S mini-album, which tempers this IDM pop opioid with the delightful Madonna throwback “Bloom”.

Orange Caramel: “까탈레나 (Catallena)”

Orange Caramel’s very existence is an interesting insight into the K-pop industry. The female trio is a subsidiary of the larger girl group After School—in the same way that Kia is a subsidiary of Hyundai. So while Orange Caramel release their own records and stage their own performances, they are deliberately perceived as an After School-brand group, a common tactic in the K-pop market (other examples include T-ara’s T-ara N4, Sistar’s Sistar19, and Girls’ Generation’s Girls’ Generation-TaeTiSeo). These derivations are typically meant to exploit the specific talents or chemistry of a subset among a larger ensemble, and Orange Caramel’s uniting concept is “Candy Culture”—basically, Korean aegyo cutesiness meets a lot of saccharine pastels.

Fortunately, this conceit has inspired some pretty fantastic pop. Orange Caramel’s best, “Catallena”, is a fluffy, filter-swept combo of ABBA-grade orchestration, ghazal folk samples, runny 1980s snare, Bollywood dyes, imitation Chic guitar, and a compression-lacquered coating of synth bass à la “Blue Monday”. The bright vocal frosting is piped preciously atop it all, flirting with an exoticized other and voicing bi-curious fancies—“She’s so great, I’ve fallen for her/ Even as a girl”—and they even sing some untranslated lyrics from the Pakistani wedding song that’s being interpolated. The holistic effect jars at first, making “Catallena” a common instance where the stickiness of a K-pop song’s video and choreography is crucial to its marketing plan. Unlike other mainstream industries, K-pop seems to romanticize the ideal of love at second listen.

CL, G-Dragon, Skrillex, and Diplo: “Dirty Vibe”

K-pop is home to a strange graveyard of gruesomely awful trans-Pacific collisions, including bewildered cameos from Kanye West, Chris Brown, and Lil Kim. But the four artists behind this track still dared to dream. The results, though buried on Skrillex’s Recess album from earlier this year, are historic: “Dirty Vibe” is visceral, exhilarating proof that K-pop and Western musicians can achieve unique things together.

G-Dragon and CL respectively hail from Big Bang and 2NE1, two of Korea’s biggest groups (both fostered by YG Entertainment, the nation’s most dependable charisma depot). Over Skrillex and Diplo’s stark trap-hall beat, the two MCs have plenty of space to flex their best; consequent boasts touch on past hits, strip clubs, Diamonds and Pearls-era Prince, and “your girl’s lesbian crush.” Further charging the 160 BPM beat with fluid bilingual modulation, a plunder of profanity, and a deeply gratifying demon’s harmony on GD’s voice, he and CL each turn in highlight reel performances. Skrillex and Diplo sound inspired as well, particularly in the thrilling anti-drop at the 48-second mark. Almost purely rhythmic, “Dirty Vibe” is as truly future-sounding as any of these four have been.

f(x): “첫사랑니 (Rum Pum Pum Pum)”

As the lead single for a blockbuster K-pop album, “Rum Pum Pum Pum” came shrinkwrapped in a blindingly bright music video. And its performances on Korea’s half dozen “Top of the Pops”-style battle shows—an exhaustive gauntlet all acts must pass to credibly promote a single—were all tightly choreographed, schoolgirl uniformed cheers. While these common tropes and marketing tactics often signify trivial music in Western pop, a peek beneath the surface of this track reveals a remarkable feat of songwriting. While retaining the familiar structure of a pop banger, “Rum Pum” makes unlikely esperanto of Middle Eastern funk guitar, clangorous samba polyrhythms, the Yuletide classic “The Little Drummer Boy”, exactly one bar of flamenco tap dance, and the ad-libbing knock of mid-aughts Timbaland. Then there’s the jazz technique of brushing circles around the beat during the bridge, about the most counterintuitive move one can make in a commercial medium where an explicitly stated beat is fundamental. The lyrics are equally intrepid, exploiting a bit of wordplay in Korean to make a love song all about wisdom teeth: “What to do? You probably expected one/ Who grew up straight/ But I’ll be crooked and torture you/ I’m not easy!” Virtually every moment of the song features a compositional quirk worthy of scrutiny.

Former robotics engineer Lee Soo-man—founding chairman of the SM Entertainment empire, and the de facto progenitor of K-pop as we know it—is a mad scientist of the music industry. His modus operandi, dubbed “cultural technology,” involves the belief that information technology’s core principles can be applied to the composition and export of Korean pop music to the global market. The exact particulars of the process are confidential, but with SM revenue topping $260 million in 2013 alone (and hysterical fans as far as Brazil crying like it’s Beatlemania), clearly there is something to the theory.

Perhaps its purest expression yet is EXO, formed as a 12-piece boy band that divides into two: EXO-K(orean) and EXO-M(andarin). These teams of six are meant to be functionally interchangeable—performing the exact same songs, dancing roughly mirrored choreographies, and filming shot-for-shot identical videos—save for their respective languages. They release their music simultaneously, and promote it in their respective territories like local branches of a single corporate entity. In K-pop, the logic of economics frequently takes surprisingly literal form in the artists themselves.

EXO are at their very best on “Love, Love, Love”, the closer for this past spring’s solid Overdose mini-album. It opens with a vinyl-cackle cascade of New Age ivory, Orientalist synth pentatonics, and Afrobeat guitar accents, soon disrupted by individual track reversals and a crater-sized bass drop. A slowburn R&B beat traces a steady groove above the bedlam, like a tightrope upon which the EXO-K boys perform increasingly daredevil acrobatics. Even after the familiar trap hats slither in, the intrinsic weirdness of the arrangement only deepens as it progresses. Though moments like the interruptive guitar fill in the bridge wouldn’t feel out of place on, say, Dirty Projector’s Bitte Orca, the song remains definitively K-pop.

Sweetune are among K-pop’s most beloved producers, and “The Chaser” is their masterpiece. The song deliberately employs traditional Korean elements, combining them with New Order guitar, militaristic horn-patch blasts, and a well-earned key change to forge one of the most virtuosic beats in the French electro style. (The instrumental is just as gratifying on its own.)

Notably, the definitive performance of “The Chaser” is a live take that features a full choir, orchestra, and rock band performing a completely new arrangement of the song to thoroughly revised choreography—all made to be performed just once. A showcase of Korea’s unrivaled performative standards, this version displays the precise way in which K-pop, at its best, elevates the disposable melodrama of teen pop toward something more like ballet.

Hidden behind one of the worst song titles imaginable is K-pop’s most convincing R&B banger to date, a gymnastic triumph in layered harmonies and falsetto. As the only other essential production from E-Tribe—the duo responsible for Girls’ Generation’s mighty “Gee”—it’s also a masterwork of micro-detailed, pitch-bent pop, and a credible challenge to Timbaland on his home turf. FutureSex/LoveSounds would have been lucky to have it.

Girl’s Day: “잘해줘봐야 (Nothing Lasts Forever)”

Now a four-piece, Girl’s Day have been Korea’s most dependable purverors of dance pop sunshine since they were assembled in 2010. Their true gift, however, lies in proficient pop songs that go suddenly, beautifully mental in the second half. Their first single to do so was “Nothing Lasts Forever” (which was featured the following summer on Elite Gymnastics’ landmark mix, All We Fucking Care About Is Kpop Whitehouse and Our Cats). The driving verses and choruses recall Ace of Base-style Eurodance refracted through primetime Lady Gaga. Then, at the two-minute mark, there’s a filter sweep into a section built around mournful piano, a mantric choir line, mesmerizing analog arpeggios, and an almost eternal note held by lead vocalist Minah. Like a sunburst, the song explodes at last into catharsis, the girls repeating their pop philosophy refrain: “Nothing lasts.”

Girls’ Generation: “I Got a Boy”

Founded in 2007 by SM Entertainment, the nine members of Girls’ Generation comprise the most iconic pop group in Asia. Though having found their popularity through bubblegum classics “Gee” and “Genie”, last year’s #1 “I Got a Boy” demonstrates their aptitude in less comfortable territory. On or off the charts, contemporary pop doesn’t get much weirder: The song is split between at least five musically distinct movements, an equal number of staggering, 40-BPM tempo jumps, a spectrum of genres covering snap music to Italo disco, multiple bars of abrupt silence, and a theatrical narrative with nine different characters. It’s like an entire musical, or rock opera, scrunched into an especially pliable pop tune.

Sometimes the tempo changes announce themselves—“Don’t stop! Let’s bring it back to 140!”—but mostly they’re meant to blindside. It’s been speculated that all this jarring tempo play references Korean club culture, where impatient DJs might switch songs after barely a chorus. But in any context, “I Got a Boy” takes chart pop’s increasing ADD in a bold new direction, and is perhaps the most structurally variable mega-hit since “Bohemian Rhapsody”. Considering the song topped all charts in Korea—with a video that has tallied more than 100 million views—Girls’ Generation prove the adventurousness of K-pop’s listenership, as well as the storytelling potential available to Asia’s pop groups.

Ga-In likes to challenge the norm in Korea, and this year’s “Fxxk U” is her crowning achievement as pop provocateur. Featuring bossa nova faux-guitar, a Casiotone beat, out-of-tune backing harmonies, and sharp stabs of arrhythmic noise undercutting the chorus, it refines the wild ingenuity of “Tinkerbell” into something subtler. But the hook leaves little to the imagination, ably delivering on its promise of the most explicit bonafide hit in K-pop to date.

Paired with its music video, “Fxxk U” breaks even fresher ground. Directed by Hwang Soo Ah, who studied film at New York University, the narrative explicates the discomfiting insinuation of Ga-In’s chorus (“Fuck you, don’t want it now...”) via an unnerving treatise on domestic violence and rape, with all the aplomb of the great Korean cinema. “Fxxk U” is one of the boldest singles of 2014, and reveals the dark depths K-pop is surprisingly equipped to interrogate. It’s an inquiry no one’s making in any mainstream pop elsewhere, let alone so artfully.

Lee Ji-eun, better known as IU, is one of K-pop’s few musician’s musicians outside the studio. As a singer, songwriter, and guitarist, she is that rare idol who fulfills the roles more commonly demanded of acts in the West, while also ably handling the ones more commonly expected of Korea’s music stars: actor, television host, model, spokesperson, and on. Composed, written, and sung exclusively by IU, “A Lost Puppy” is a lament of astonishing hopelessness coming from a lighthearted 18-year-old icon.

B2ST: “Fiction (Orchestra Ver.)”

Pronounced “Beast”, this boy-band sextet is a product of the K-pop industry’s competitive cruelty. Comprised of reject trainees from big-league agency JYP (plus one ejected member of the now-super-massive Big Bang) B2ST barely escaped the purgatory to which 10,000 trainees are damned for every one star the system births. And when the group debuted in 2009, the public dismissed them as a “recycled group” made of better groups’ trash.

But B2ST’s Fiction and Fact stands as one of the best K-pop albums to date, quick to convert skeptics with its gargantuan hit, “Fiction”. The song’s morose tones, cinematic scope, and superbly poetic lyrics, along with the most effectively understated choreography in K-pop, left an impression on the market that still holds today. Even better is this elegant reimagining, which coaxes the song’s essential beauty to the fore. The ethereal arrangement of harps and strings even manages one of the unlikeliest accomplishments on this list: rap that works over a symphony instead of a beat.

Featuring CL, K-pop’s most beloved star in the West, this girl group recently released Crush, among the first full-lengths a K-pop neophyte should try. But “Missing You”, a standalone single cut from the album’s extensive sessions, is not to be missed either. Beating Lana del Rey’s “West Coast” to the punch by half a year (and without that song’s cop-out radio mix), “Missing You” is the rare band-format single that actually slows downs for the chorus. The song begins with a tense, guitar-based verse glossed in the kind of production glitz that forecasts dancefloor absolution around the bend. But instead, the tempo drops from 130 to a loose half time, all acoustic guitar, grand piano, vocal harmony, and falsetto melisma. Most remarkable, however, is the song’s whole-step modulation before an extended outro that introduces entirely new chord progressions, melodies, and lyrics. “Missing You” is one of the most vocally rich and structurally distinctive singles Korea’s ever produced, a strength 2NE1’s younger brother group Winner emphasized in their equally beautiful live cover.

SHINee: “1분만 (One Minute Back)”

Debuting in 2008 as SM’s most androgynous boy band, the five stars of SHINee have grown into some of the best singers and dancers in contemporary pop. Though characteristically hard-working in the K-pop tradition, the group had an especially ambitious 2013: three full-length albums, a seven-song EP, several standalone singles, a world tour, regular radio DJing gigs, lead roles in soap operas, and more. When they won artist of the year at the People’s Choice-style MelOn Music Awards, the group tearfully begged their fans’ pardon throughout their acceptance, apologizing for not yet truly deserving it—as succinct an illustration of the difference between the American and Asian celebrity mindsets as any.

The brightest diamond from their big year is “One Minute Back”, the pop prog centerpiece of their stellar Everybody mini-album. The first 90 seconds alone could flip Yes’ wigs, reconciling a battery of multidirectional beats; disruptive plain speech; a pre-chorus polyrhythm that sounds like Neil Peart went trap; a hellish descent into one very satanic, five-bar invocation; and at least one vocal harmony that’s as chordally ambitious as Queen’s daringest. The rest of the song doesn’t let up, either.

Brown Eyed Girls: “Sixth Sense”

The group that Ga-In calls home is one of Korea’s strongest vocal powerhouses, allowing Brown Eyed Girls to go places many their peers can’t. Their 2011 hit “Sixth Sense” is perhaps their most aerobic outing to date, a larynx-limber tribute to the Motown pop model whose influence in Korea is felt mostly in the boardroom. Splitting the difference between the bravados of classic girl-group R&B, early-action-film scores, and disco circa Gloria Gaynor, “Sixth Sense” peaks in a high-note climax many would envy in Korea and beyond.

Girl’s Day: “기대해 (Expectation)”

Last year, this single initiated Girl’s Day’s ascent in the Korean mainstream. It’s easy to hear why: Channeling a more steroidal strain of ‘90s Eurodance, “Expectation” is one of the most effective club bangers K-pop can claim. Sojin and Minah soar through dynamic, falsetto-peaking verses reminiscent of La Bouche, while the chorus —driven home by its now-iconic choreography—spoils with an even wilder abundance of hooks.

But again, the second half is where Girl’s Day truly shine. After Yura’s rap break in the Hi-NRG post-chorus, the song plateaus for an extended bridge that builds into a key change so effective it’s almost something of a riddle. Pop songs don’t end quite like that anymore; club songs never have.

K-pop is a closed-circuit game. Considering the stranglehold grip just a few mega-monopolies have on the only distribution channels that matter—the ones on Korean cable—it’s all but impossible to be heard if you aren’t willing to play ball. The Korean mainstream is a carefully regulated monoculture; there are a small handful of rock bands that have gone rogue and lived to tell, but finding a genuinely independent voice of any quality or significance in K-pop is no mean task.

So Neon Bunny is a rare breed—writing the type of bedroom producer K-pop the industry is designed to expunge. This year’s “It’s You” is a particularly fine torch song, illuminating a warm space between French electro synths and the subtlest of glitch-hop fills and trap hi-hats. Her voice is imbued with a natural feeling not often found in the method-acted emotions of mainstream, trainee-bred K-pop, and the industry has much to learn from the brave few like her.

Last year’s Pink Tape may be one of the best Asian pop albums of all-time, but f(x)’s just-released Red Light is no joke, either. Its chart-topping title track might briefly seem like little more than an expert trap beat, but it soon reveals a clever subversion: instead of a straight-ahead verse followed by a groovy, half-time drop, “Red Light” inverts the EDM formula to do the exact opposite. On first listen, the effect feels violent, even malicious—just as the five girls have primed us for some familiar wobble with their Melodyne-slick harmonies, what we get instead is more like a runaway freight train in reverse. But sometime during the motion-sick post-chorus it all clicks, and by the second go around the sudden vertigo is like a thrillseeker’s high.

Modern Korean music’s comfort zone lies in unadulterated bubblegum pop, and this list would be incomplete without acknowledging its magnum opus. “Gee” is K-pop at its most mathematically reduced, radically pure essence—a pop song so formally irrefutable that, for one golden year, it overcame half a millennium of historical animosity to broker pop cultural peace between Korea and Japan. Domestically, it is the most popular South Korean song of its decade. And most international K-pop fans, consciously or not, owe their obsession to the butterfly effect “Gee” set into motion upon its 2009 release.

The idea of writing an original thought about “Gee” is, for the K-pop connoisseur, like trying to find a fresh insight in Abbey Road or The Great Gatsby. It’s hardly necessary; a tale of first love that transcends the language barrier, “Gee” speaks for itself. It was a flash of brilliance so bright that the production duo behind it could only sputter and fail from there. In a way, that feels appropriate: “Gee” is the greatest feat Korea will ever accomplish in traditional songcraft. From here, K-pop’s true future lies in the experimental, the experiential, and the unexplored.

Madlib in Los Angeles circa 2002. Photos by Eric Coleman.

Madlib in Los Angeles circa 2002. Photos by Eric Coleman. Madlib's recording setup in Sao Paulo, Brazil, circa 2002. Photo by Madlib.

Madlib's recording setup in Sao Paulo, Brazil, circa 2002. Photo by Madlib. DOOM in Los Angeles circa 2002. Photos by Eric Coleman.

DOOM in Los Angeles circa 2002. Photos by Eric Coleman. Madvillain in Los Angeles circa 2004. Photo by Eric Coleman.

Madvillain in Los Angeles circa 2004. Photo by Eric Coleman. DOOM and Madlib in Los Angeles circa 2002. Photo by Eothen Alapatt.

DOOM and Madlib in Los Angeles circa 2002. Photo by Eothen Alapatt.

Dream Tattoo

Dream Tattoo Photo by Philipp Virus

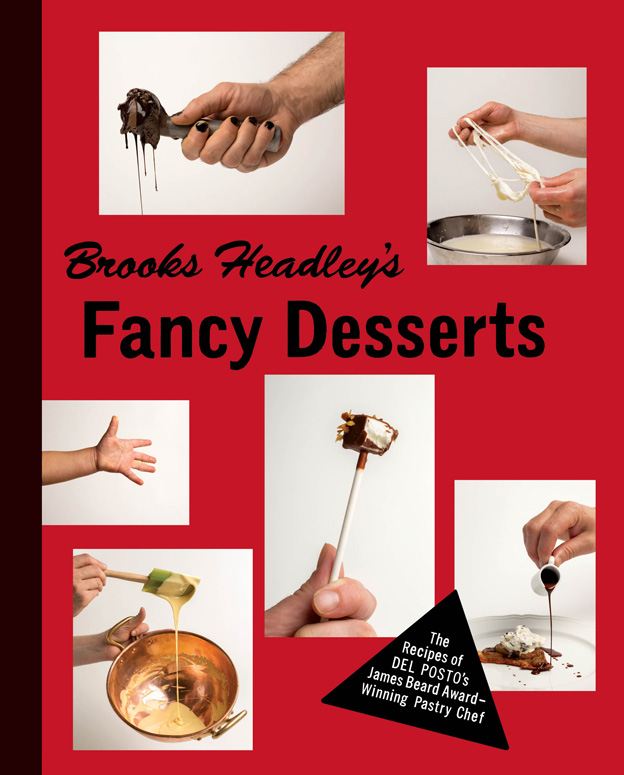

Photo by Philipp Virus What I'm Reading Right Now

What I'm Reading Right Now

I've always been a huge

I've always been a huge